Colin Powell - Washington interview

The former US Secretary of State was at the forefront of post-9/11 international relations. In conversation with IBA Director of Content, James Lewis, he discusses past and present concerns – from the lessons of the Iraq War, to UN inaction over Syria.

James Lewis (JL): My first question is about leadership. One of your maxims of leadership is: ‘It’s never as bad as you think’. Now I wonder if that’s what you’ll be saying to whoever turns out to be the next US President, whether it’s Hillary Clinton or Donald Trump?

Colin Powell (CP): I say that to everybody. The whole sentence is: ‘It’s not as bad as it looks. It’ll be better in the morning’. I’ve used it throughout my career in talking to audiences about leadership. This isn’t a prediction – I don’t know if it’ll be better in the morning or not – but it’s an attitude.

When you end the day, no matter what problem you’re having, no matter how difficult the political situation or the military situation might look; no matter what you think about what’s going on in the country, it will look better in the morning if you make it better. Leadership is all about making things better and you do that through followers.

In the case of politics, the followers are the people, as opposed to subordinates, and so leadership is about making sure you give the people – your fellow citizens – a vision for tomorrow and you’re telling them that you’ll lead them to this vision.

That’s what leadership is all about, and as we watch the US presidential campaigns unfold in the last couple of weeks, and as we watch the debates, the question every American will have to answer is: ‘Which one of these two individuals is going to take me where I think the country needs to go? Who is best qualified to give me that vision?’ and ‘prove it to me’.

JL: That’s a very positive-minded vision. But given events in Syria, the rise of ISIS, terrorism, other events unfolding around the world, do you think there’s more of a challenge now than there’s ever been?

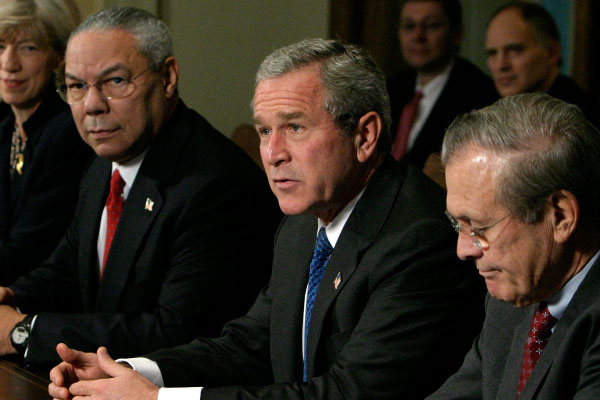

US President George W Bush speaks during a meeting with members of his cabinet at the White House in Washington, DC, 4 November 2004. Bush is flanked by Secretary of State Colin Powell (L) and Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld (R).

CP: I’ve always lived in a time of challenge. I served in the army when we were facing a thermonuclear war that could destroy us, and that’s now gone. Even though there are dangers out there and some nuclear powers we have to worry about, we’re not at existential risk of destruction.

We have to put that in context. The former President of Israel, Shimon Peres, once said something to me after the Cold War was over which I’ve never forgotten: ‘We’ve lost our enemies, now all we have are problems’.

So there are lots of problems, and one of them, of course, is Syria. This is such a complex problem that I’m not sure there’s a single solution. What I’d like to see is some agreement to end the fighting, some ceasefire that sticks, and then maybe we can sort out the various pieces. But as long as we’re bombing and shooting and arguing with each other, we’re not going to get a solution.

It’s fairly clear that President Assad’s position is strong enough that he will remain in position for some time to come. Be careful about demanding an immediate departure, because you’re not going to get it. The people are suffering; buildings are being blown up; cities are being destroyed; people are being driven from their homes. So let’s work on bringing down the level of violence and perhaps getting to a ceasefire, so we can begin the political process.

My advice to him was: Mr President, if we can avoid a conflict, we ought to avoid it

JL: Moving on to the so-called ‘war on terror’; you’ve expressed serious misgivings about the damage it’s having on America’s moral authority. How bad is it?

CP: A moral authority is very important in whatever you do in life or in politics, but the terrorists who are coming after us demonstrate no moral authority; they demonstrate no morals at all. You have to respond to that threat in many ways: more law enforcement activity, more intelligence activity, and if necessary go after the terrorists, wherever they are. Above all, don’t lose your confidence in your society and don’t become so paranoid about terrorism that you start to do things that are not consistent with your moral standing and your moral ability.

In the US, in the years since 9/11, we’ve lost about 400 citizens to terrorist activity, both overseas and at home. I’m saddened by the loss of any individual, but it is a fairly small number, considering the 3,000 we lost in one hour 15 years ago.

JL: When you were Secretary of State, you warned President George W Bush about the potentially dire consequences of the war on terror, and, in particular, intervening in Iraq without the support of the United Nations. Are we seeing those dire consequences now to their fullest extent, or could it get worse?

CP: We don’t know if it will get worse or get better. I hope it will get better. We tried to avoid a war, and my advice to the President was that he take the problem to the UN because they’re the offended party: he did and we got a resolution unanimously from the Security Council that demanded Saddam Hussein give us the information we needed to see whether or not he possessed weapons of mass destruction. He failed and, as a result, the President decided military action was appropriate. He’s the Commander -in-Chief; he’s responsible for the safety of the country.

He had already been given authority to do that, if necessary, by the US Congress. He had allies with him on this. He had allies who did not think it was appropriate, but when you’re US President, you have to do what you think is appropriate to protect American citizens.

We went into Iraq and took down Saddam rather quickly. It was the aftermath that was the real problem. We, or the Iraqi’s, didn’t put a functioning Iraqi government that represented all the people in place fast enough.

We made some strategic errors removing the Iraqi army. We were counting on it initially to be the source of security for the people, and stopped anybody who had ever been in the Ba’ath Party from being in government again. But a lot of those people had to be in the Ba’ath Party just to be a schoolteacher or a nurse. That was a mistake.

And then the insurgency broke out, to some extent fuelled by these soldiers who suddenly weren’t in the army anymore. We were slow in responding to that insurgency, and it took several more years to bring about stability. But the problem was then given to the Iraqi leadership, and I don’t think they did enough to bring the people together. There were too many sectarian differences that didn’t allow that to happen.

So you can always hope for it to be better tomorrow, but I think the Iraqis have got a lot to do to make sure that corruption is ended, and that all parts of the Iraqi populace are brought into the process. Whoever the next US President is, we will have to continue to support Iraq, but ultimately the answer rests in the hands of the Iraqis.

Don’t become so paranoid about terrorism that you start to do things that are not consistent with your moral standing

JL: Going back prior to George W Bush being convinced that he was going to overthrow Saddam Hussein by force, were you averse to that position initially?

CP: My position was to avoid a war. My advice to him was: ‘Mr President, if we can avoid a conflict, we ought to avoid it, and the way to do so is go to the UN and ask for a resolution that gives Saddam a chance to avoid what’s going to happen to him’. That’s what the President did with my recommendation, and with the concurrence of Vice President Cheney and all of the Administration.

Saddam did not do that, and once the President decided that military force was appropriate, I supported him all the way through, until we had sort of a difference of opinion with the Administration about the aftermath of the war and how to handle that.

JL: You’ve spoken about the difficult situation of the UN Plenary Session in February 2003, where you were put in a position of trying to get the UN to back the use of force, and unfortunately it turned out subsequently that the argument was being based on fundamentally flawed intelligence. What have you learned from that experience?

CP: It was a very great disappointment to me, it was a disappointment to the President, to all of us, because we were assured by a very exstensive national intelligence estimate that weapons of mass destruction were there. It was that national intelligence estimate that persuaded the US Congress to support the President. It was the basis upon which the President made the decision.

What he sent me to the UN to do was to present our case to the world, hoping the UN would support it but knowing that there were some who would never approve another resolution. The President went to combat because he thought it was necessary, and I supported that thoroughly.

After Baghdad fell, we went back to the UN for about five separate resolutions to help restore peace, restore the government and give the Iraqis the help they needed. So the UN came together after that, but unfortunately the insurgency stopped that in its tracks for a few years. Also, the UN representative there, Sérgio Vieira de Mello, was killed, and the UN felt they had to leave for the moment and come back later.

JL: After your experience at the UN and discovering that the intelligence was flawed, did you instigate an overhaul of the intelligence gathering initiatives?

CP: I had no responsibility for the intelligence gathering activity; I was Secretary of State.

JL: So you didn’t feel there needed to be any tightening of that?

CP: Eight months after the conflict, the CIA looked at it all. They put out a statement saying ‘we haven’t found anything, but we stand by the judgements we made then’. Ultimately, two commissions were created to look at the intelligence, and both found fault with the way in which it was done by the CIA. They’re the ones who decided an overhaul was necessary. Between the President and Congress, they determined that a new office should be created to supervise all 16 agencies: the Director of National Intelligence.

Not being in the intelligence community and being a diplomat, it was not my place to reorganise it, although I expressed my disappointment, and the problems I had with the community at the time.

Syria is such a complex problem. What I’d like to see is some ceasefire that sticks, and then maybe we can sort out the various pieces

JL: Given the difficulties of getting the UN to act on Syria, the UN really is essential but is broken. What, in your view, needs to happen to allow it to do what it was intended to originally?

CP: What is it you think the UN is not doing that it should be doing?

JL: It should be free to act; there should be less veto in the Security Council; it should be able to intervene in situations like Syria.

CP: The UN cannot act if the Security Council does not act. One could then ask the question: should the Security Council be reorganised? It’s been debated for decades.

JL: What’s your view?

CP: Certainly, I think it’s worth reviewing, but the fact of the matter is they would have to approve their own reorganisation, which is not likely to happen anytime in the future.

It’s something that came out of the Second World War, with the five nations that came out as victors. They created it in a way that any one of them could block an action by the Security Council. So I don’t know that the UN has much authority to do more than what it is doing now. I don’t think the UN can solve this one [Syria], because they’re trying to apply diplomatic pressure but they don’t have the military means to go and solve this, nor would it be appropriate for them I think.

What we need now is a ceasefire, and that should be possible with Russia and the US working with other nations concerned. But you’ve got to get the belligerents, those who are fighting, to agree to a ceasefire – that’s on the basis of stopping the killing of innocent people; stopping the destruction of cities; stopping this creation of refugees and displaced people – and then figure out how to solve this politically. That’s a very tough request to make. I’m always hopeful but unfortunately I don’t see it happening anytime soon.