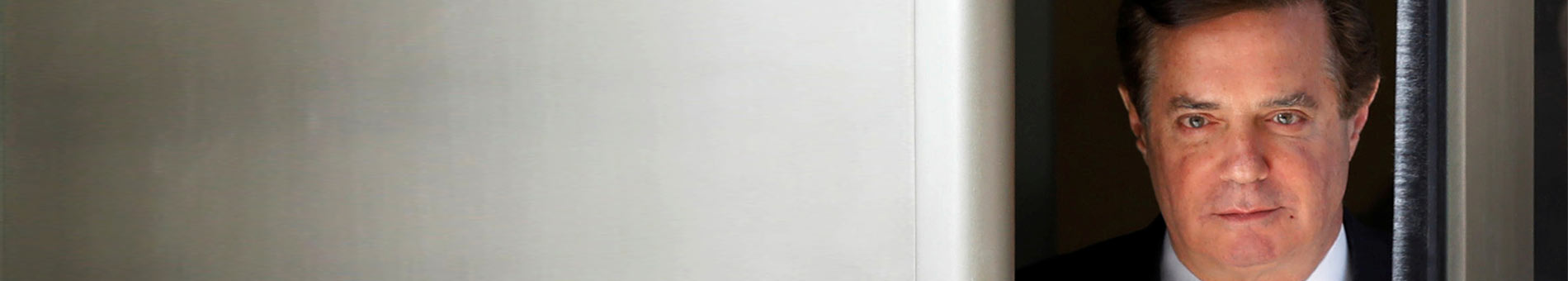

American presidency: judges weigh crimes of Trump campaign chief Manafort in major wins for Mueller probe

In a pair of sentencing hearings in the second week of March, two judges rendered the different judgments of the two Americas for the crimes of Paul Manafort, who served as President Trump’s campaign chief.

The sentences mark the most significant wins for Special Counsel Robert Mueller since he launched his investigation nearly two years ago into 'any links and/or co-ordination between the Russian government and individuals associated with President Donald Trump’s campaign'. The role of Paul Manafort goes to the core of the Special Counsel’s investigation.

‘‘It’s hard to overstate the number of lies and the amount of fraud

Judge Amy Berman Jackson

In total, Manafort was sentenced to seven-and-a-half years in federal prison (minus nine months of time served), on a maximum potential sentence of 34 years. Prosecutors also moved in early March to seize about $24m of Manafort’s real estate, bank accounts and life insurance.

Judge T S Ellis III, appointed by President Ronald Reagan, gave Manafort just under four years in prison – on a maximum recommended sentence of 24 years – after a Virginia jury convicted him of multiple tax and bank frauds. Judge Ellis stated Manafort has 'earned the admiration of a number of people' – and lived 'an otherwise blameless life'.

Judge Amy Berman Jackson, appointed by President Barack Obama, gave Manafort the statutory maximum of five years for a broad conspiracy to defraud the US, to which he pleaded guilty, also encompassing money laundering, secret foreign bank accounts, and secret foreign lobbying. Remarking that Manafort’s 'moral compass' is broken, Judge Jackson said it’s 'hard to overstate the number of lies and the amount of fraud' he committed merely 'to sustain a lifestyle at the most opulent and extravagant level'.

Because of overlapping conduct, Judge Jackson made half the conspiracy sentence concurrent with Judge Ellis’s. She gave Manafort a year in prison, on a statutory maximum sentence of five years, for witness tampering.

Former US Attorney for Michigan, Barbara McQuade, called Ellis’s sentence 'absurdly low', and Jackson’s somewhat lenient, though well-reasoned. Former federal prosecutor Seth Waxman found Ellis’s sentence 'extremely light' and Jackson’s 'a bit light', but perhaps justifiable as Manafort is turning 70. McQuade felt it was 'still too low for such egregious conduct', and possibly too lenient to deter a conspiracy so lucrative.

Judge Ellis called the sentencing guideline 'way out of whack'. He complained that the Justice Department treats secret foreign bank accounts with undue seriousness and expressed the wish to avoid sentencing disparities between similar defendants. For example, he recalled giving only seven months to a man who’d hidden $200m in overseas accounts.

McQuade criticised Ellis for ignoring the guidelines based merely on his sentiment that they are too high for certain white collar crimes. 'You don't hear that sentiment expressed about other kinds of crime,' says McQuade. If Manafort demonstrates any disparities, he 'demonstrates the disparities between the haves and the have-nots'. A day before Manafort got 47 months, Brooklyn public defender Scott Hechinger saw a client offered 36-72 months 'for stealing $100 worth of quarters'.

To view Manafort as 'otherwise blameless' is highly questionable. Manafort’s plea admitted all the conduct in the ten counts on which the jury hung, as well as the lobbying offences on which he’s not been tried. It’s notable that prosecutors rarely appeal low sentences as their only remedy is resentencing before the same judge.

Prosecutor Andrew Weissmann argued to Judge Ellis that Manafort’s crimes 'served to undermine and not promote American ideals'. After helping elect Ronald Reagan president in the 1980s by stoking racial resentment, Manafort broke the taboo against campaign consultants peddling their influence with politicians they got elected. He then pioneered US influence peddling for a rogues' gallery, including Ferdinand Marcos, Daniel Arap Moi and Sani Abacha.

Manafort exported the dark arts of US campaign consulting to foreign figures exemplified by ex-convict Viktor Yanukovich, whose earlier efforts to steal the Ukrainian election triggered the Orange Revolution. Harking back to his Reagan playbook, Manafort resurrected Yanukovich by stoking hatred between Ukrainian and Russian speakers. Manafort collected millions in secret payments, as Yanukovich distributed the Ukraine’s wealth to allied oligarchs and looted an estimated $40bn from the Treasury.

Significantly, court papers refer to an alleged liaison at a New York cigar bar in August 2016 between Manafort and Kyiv collaborator Konstantin Kilimnik, who is linked by Robert Mueller to Russian intelligence. According to the papers, Manafort shared 75 pages of Trump campaign polling data with Kilimnik before each of them left by separate exits. At pre-sentencing hearings, one prosecutor told Judge Jackson that this meeting goes 'very much to the heart of what the Special Counsel’s Office is investigating'.

Manafort has admitted reaching out through Kilimnik to tamper with witnesses at his trial. And Judge Jackson later found that Mueller was justified in voiding Manafort’s cooperation agreement because Manafort repeatedly lied to Mueller about Kilimnik.

Judge Ellis noted at his sentencing that he had never 'decided the wisdom or appropriateness of delegating to special prosecutors broad powers'. In a revealing pre-trial moment, the judge exclaimed: ‘You don’t really care about Mr Manafort’s bank fraud. What you really care about is what information Mr Manafort could give that would reflect on Mr Trump and lead to his prosecution and impeachment.’

By contrast, Judge Jackson dressed down Manafort’s lawyers for suggesting she had found 'no collusion' – as collusion had never been charged, and was never under discussion before either judge. ‘Court is one of those places where facts still matter,’ said Judge Jackson.

Nevertheless, on the steps of the court, Manafort lead lawyer Kevin Downing told the press: 'Judge Jackson conceded that there was absolutely no evidence of any Russian collusion in this case. So…two courts have ruled no evidence of any collusion.' Hecklers drowned out Downing with cries of 'that’s not what she said!' and 'you’re a liar!'

‘The hecklers had the better of that argument,’ says Waxman. ‘Neither judge made a finding that there was or was not collusion.’ McQuade was shocked. ‘Judge Jackson clearly said this case is not about collusion, and to suggest otherwise is wrong. For Downing then to go out on the courthouse steps and carry on a disinformation campaign was quite bold and inaccurate. I can’t believe he had the nerve.’