The Panama Papers: tipping point for reform

Jonathan Watson

The record leak of 11.5 million documents shed unprecedented light on the workings of the world’s financial centres. Public opinion has shifted markedly and the benefits of ending years of destructive secrecy are now fully established.

The Panama Papers, a leak of 11.5 million files from the database of law firm Mossack Fonseca, has provided considerable ammunition for critics of the legal profession. The leak highlights the creation of layers of secrecy that allow individuals and companies to hide assets from the authorities.

The activities revealed in the Panama Papers, said the anonymous source behind the leak in a statement issued in May, show that ‘the legal profession has failed’. The source argued that ‘lawyers have become so deeply corrupt that it is imperative for major changes in the profession to take place, far beyond the meek proposals already on the table’.

Mossack Fonseca did not work in a vacuum, the source said. ‘Despite repeated fines and documented regulatory violations, it found allies and clients at major law firms in virtually every nation… it is undeniable that lawyers can no longer be permitted to regulate one another.’

The major opportunity for reform is to push for changes in those jurisdictions which allow beneficial ownership to remain unknown

Leopoldo Pagotto

Secretary, IBA Anti-Corruption Committee

So far, the leak has led to high profile resignations, including the prime minister of Iceland, triggered official inquiries in multiple countries and put pressure on world leaders and other politicians, such as UK Prime Minister David Cameron, to explain their connections to offshore companies.

‘Politicians across the world appear to be hopelessly compromised,’ says Robert Wyld, partner at Australian law firm Johnson Winter & Slattery and Co-Chair of the IBA

Anti-Corruption Committee. ‘On the one hand, they say tax avoidance/evasion (which is never clearly stated) must be stopped, and yet at the same time, they create laws which permit opaque structures to exist. They are then potentially, as it is alleged in the media, involved in, benefit from or know about these structures from which they may have received benefits, directly or indirectly.’

The Panama Papers have also crystallised public opinion around two specific policies: public registers of the beneficial owners of companies, trusts and foundations and the automatic exchange of tax information, says Alex Cobham, research director at the Tax Justice Network. ‘After this leak, the public now understands that the key problem is the anonymity of ownership,’ he says. ‘It’s no longer enough for governments to say “we’re going to crack down” and then move on.’

Leopoldo Pagotto is Secretary of the IBA Anti-Corruption Committee and Of-Counsel at Trench, Rossi e Watanabe in Brazil. ‘The major opportunity for reform is to push for changes in those jurisdictions which allow beneficial ownership to remain unknown,’ he says.

The global response

Many administrations are attempting to act. Since 6 April, all unlisted UK companies and limited liability partnerships (LLPs) have had to maintain a register of the people who have significant control over them. Such registers are available for public inspection and, from 30 June 2016, the information will be searchable online via Companies House, a government agency.

Others should follow this lead, says Daniel Castro, director of think tank the Center for Data Innovation. ‘So far, most European countries have failed to make even the most basic company data available,’ he says. ‘The 2015 Open Data Census assessed 20 EU countries and found that other than the UK, only Romania made the bare minimum – company name, unique identifier, and address – available as open data. And countries like Spain, where the minister of industry, energy and tourism resigned following leaked details about his involvement in an offshore company in the Bahamas, provide virtually no access to this data.’

We must recall that states agreed in 2016 that one of the Sustainable Development Goals is to reduce illicit financial flows by 2030

Thomas Pogge

Director, Global Justice Program, Yale and Chair of the IBA Task Force on Illicit Financial Flows, Poverty and Human Rights

The UK government hosted an anti-corruption summit in London on 12 May at which six countries – Afghanistan, France, the Netherlands, Nigeria, Kenya and the UK – agreed to publish registers of beneficial ownership. Six more, including Australia, agreed to consider doing the same.

In the run-up to the event, more than 300 economists from 30 countries had signed a letter to world leaders, arguing that there is no economic justification for allowing tax havens and urging them to lift the veil on offshore secrecy.

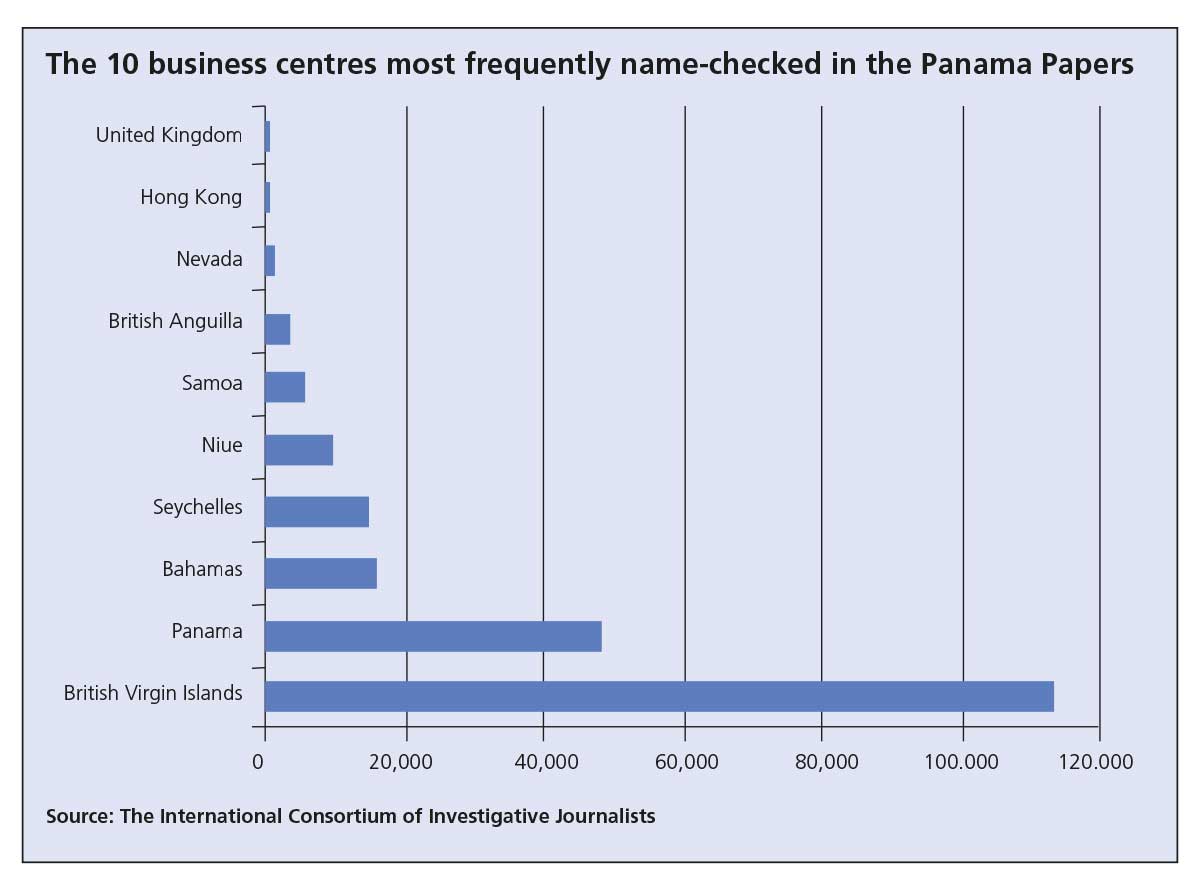

However, Britain’s overseas territories and Crown dependencies – such as the British Virgin Islands and Jersey – did not pledge to create a public register. These territories feature heavily in the Panama Papers. Of the companies that appear in the leaked documents, half – more than 113,000 – were incorporated in the British Virgin Islands.

In the US, where several states act as tax havens for people from all over the world, the Treasury has pledged to send legislation to Congress requiring companies set up in the country to report their real owners to the agency’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network.

Sigmundur David Gunnlaugsson became the first political casualty after the Panama Papers prompted more than 20,000 demonstrators in Reykjavik to call for his resignation.

‘A lot of it’s legal, but that’s exactly the problem,’ said US President Barack Obama in his initial reaction to the Panama Papers.

‘It’s not that they’re breaking the laws, it’s that the laws are so poorly designed that they allow people with enough lawyers and accountants to wriggle out of responsibilities that ordinary citizens are having to abide by.’

Many lawyers are well aware of the role of US states in helping the wealthy avoid tax. ‘The US is running around beating people around the head and shoulders for being tax havens when in reality, it is just as big a sinner as everyone else,’ says Edward H Davis Jr, founding shareholder at Astigarraga Davis and North America Regional Officer for the IBA Anti-Corruption Committee.

Jan Lawrence Handzlik, a US-based investigations and trial lawyer and Co-Chair of the IBA Business Crime Committee, says it is perhaps surprising that so few US owners of offshore companies have been identified in the Panama Papers. ‘Most of the 200,000 companies and 15,000 owners are primarily from countries other than the US,’ he says. ‘We don’t really know why that is – there is still much more to come from this leak – but maybe the criminal law is acting as a deterrent. The draconian penalties in place now and the threat of prosecution that exists in the US have caused a lot of people to think twice and to pull back from these activities.’

The Panama leaks have opened a genuine opportunity for reform, says Thomas Pogge, director of the Global Justice Program at Yale and Chair of the IBA Task Force on Illicit Financial Flows, Poverty and Human Rights.

‘We must recall that states agreed in 2016 that one of the Sustainable Development Goals is to reduce illicit financial flows by 2030,’ he says. ‘Yet, if we entrust it to the elites, this opportunity will be lost. We must understand the promising reform proposals and mobilise in their support.’

Wyld says the Panama Papers have exposed the hypocrisy that exists when it comes to international taxation regulation and enforcement. ‘On the one hand, governments across the world have created laws that permit legal structures to be created for generally quite legitimate purposes,’ he says. ‘All of the structures that seem to have emerged from Panama are, in all likelihood, entirely legal – the question is, what do the principals behind those structures do with them?’

The unprecedented leak of documents shows how vast loans worth $2bn have made members of Putin’s close circle fabulously wealthy.

This is the question that company formation agents will now have to answer, says Davis Jr. ‘They claim they can’t be held responsible for what happens after they form an offshore corporation,’ he says. ‘However, if you have designed a strategy of anonymity, sought out clients and customers to use it and don’t adequately “know your customer” then you are likely aiding and abetting illegal conduct and you can’t stick your head in the ground and pretend that it isn’t so. Formation agents, and others who are involved such as banks, brokerage houses, lawyers and accountants can and should be equally held accountable.’

Nicola Bonucci, Director for Legal Affairs at the OECD and former chair of the IBA Anti-Corruption Committee believes the international community should focus not just on the automatic exchange of information, but on the quality of that information – for beneficial ownership in particular. ‘Public registries will be very useful, but what is more important for us is the quality of the information they contain,’ he says. ‘What we are really pushing for is very accurate and frequently updated information on who is the real beneficial owner for these structures.’

A lawyer’s responsibility

From a lawyer’s perspective, the key point in the Panama Papers is that a law firm was apparently actively helping clients to launder money, says Pagotto. ‘This raises a question about lawyers’ behaviour when approached for legal advice,’ he says. ‘Some appear to consider professional privilege as completely inviolable, but it seems quite clear that the lawyer should say no if asked to assist in illegal behaviour. Lawyers should advise very strongly against this.’

The golden rule is of course to ‘know your client,’ Pagotto adds. ‘If someone shows up at a lawyer’s office with a briefcase full of cash and won’t say where it came from, it is clear that the lawyer should not agree to assist them.’

Mossack Fonseca says that media reports about the firm ‘rely on supposition and stereotypes, and play on the public’s lack of familiarity with the work of firms like ours’. The company adds that it has never been accused or charged in connection with criminal wrongdoing, noting that it is ‘legally and practically limited in our ability to regulate the use of companies we incorporate or to which we provide other services.’

It is now time for the legal profession (and others) to ensure that what they are asked to do is for reasons that are not only legal but also legitimate, says Bonucci. ‘The border is not always very clear, but it is possible to do something lawful which is awful. Making this clear has to be part of the ethical code of law firms.’

At the London anti-corruption summit, IBA president David Rivkin noted that lawyers play a vital role in investigating, prosecuting and bringing to justice those who are engaged in corruption. ‘They are an essential part of the battle against corruption,’ he said. The IBA has undertaken considerable work in the areas of anti-corruption, combatting money laundering and, last year, launched a Judicial Integrity Initiative aimed at eliminating judicial corruption.

It’s early days, but transparency is here, and it’s here to stay

Edward H Davis Jr

North America Regional Officer,

IBA Anti-Corruption Committee

The impact of the Panama Papers varies from country to country. Pagotto says their impact in Brazil has been different to other jurisdictions due to the scale of the problems already engulfing the country. ‘Compared to the corruption scandals we have here in Brazil, the story from the Panama Papers so far looks like taking candy from a baby,’ he says.

They have not had quite the same impact in Italy either, but for a different reason, explains Fabio Cagnola, Co-Chair of the IBA Business Crime Committee. ‘Last year, the Italian parliament passed a law that set up a voluntary disclosure programme,’ he explains. Those participating had to pay all outstanding taxes when regularising their undeclared assets held abroad, and in return for this, they were then subject to greatly reduced administrative and criminal penalties. ‘From the descriptions provided by taxpayers who decided to use this tool, it emerged that many of them retained assets in Panama,’ Cagnola says. ‘So we were not surprised by the Panama Papers.’

Relatives of various members of the top leadership of China’s Communist Party, including President Xi Jinping, have offshore holdings.

The Panama leak does provide further impetus for the reform of tax havens. It will also spur law firms to take proactive steps to prevent leaks such as the one from Mossack Fonseca. ‘I don’t think it’s necessarily going to lead to people seeing the light or to the end of these practices,’ says Handzlik. ‘I would assume that the problem is really much larger than what we can see in this one scandal.’

Davis agrees that this is just the tip of the iceberg. ‘The “Panama Papers” is a horrible misnomer,’ he says. ‘Only a fraction of these corporations are from Panama. The rest of them are from the global empire in which Mossack Fonseca formed corporations for the use of people who want to remain hidden.’

Davis believes that if anyone needs to own a corporation anonymously to do whatever they’re doing, then the presumption should arise that it’s illegal or improper. ‘It may be possible to rebut that presumption, but the onus should be on the individual in question to do that,’ he says.

Tax havens have always existed and always will, adds Cagnola. ‘But measures can be adopted to reduce their role, even if they are unlikely to be eliminated altogether.’

Brussels proposes further action

The European Commission is also getting in on the act. In April, it unveiled draft legislation that would require large multinationals operating in the EU to publish reports disclosing profits earned and taxes paid in each of the 28 Member States, as well as tax havens. All large companies trading in the EU, including subsidiaries of

non-European businesses, would have to publish how much tax they pay outside the EU, including detailed country-by-country information on their finances in tax havens.

Only companies operating in the EU with annual revenue of more than €750m ($856m)would have to publish the reports, which would also include details on business operations, such as the number of employees and the nature of activities in different tax jurisdictions. That information would be made available on a company’s website for at least five years.

According to the ONE Campaign, an NGO, this restriction would leave out 85 per cent of multinationals and set the wrong precedent. ‘Especially in developing countries “smaller” multinationals can have a huge impact, as the example of the company London Mining shows,’ the organisation says. The company has a global turnover of ‘only’ €226m, but its activities in Sierra Leone represent ten per cent of the country’s GDP.

The Commission argues that the €750m threshold ‘strikes the balance between targeting the most relevant companies and avoiding unnecessary administrative burdens on smaller players’. It also enables the proposal to cover those companies controlling approximately 90 per cent of corporate revenues made by multinationals, according to OECD figures.

Aggressive tax avoidance, even if it is legal, is no longer acceptable

Nicola Bonucci

Director of Legal Affairs, OECD and former Chair, IBA Anti-Corruption Committee

‘What they’ve called for is very weak,’ says Cobham. ‘Unless you publish all the available data, you are seriously undermining the whole point, as you do not have the information you need to make valid comparisons. The mood is such that I don’t think this proposal will hold.’

Either way, wide-ranging international rules can be difficult to enforce. Some countries, like Italy, have decriminalised tax avoidance in the past, says Cagnola. ‘Brussels tries to take a harsher stance but some countries are taking the opposite route – they are taking a lenient stance on tax avoidance.’

Despite this, it seems clear that in the wake of the Panama Papers, perceptions are shifting.

‘It’s early days, but transparency is here, and it’s here to stay,’ says Davis. Faced with tax avoidance on a huge scale, it is no longer good enough simply to say ‘this is all perfectly legal’.

We are living in a post-crisis society that hasn’t actually recovered from the crisis, says Bonucci. ‘It’s a world in which a lot of the world’s citizens have been forced to make sacrifices. Taxes have been raised and public services have been reduced. Aggressive tax avoidance, even if it is legal, is no longer acceptable.’

Jonathan Watson is a journalist specialising in European business, legal and regulatory developments. He can be contacted by e-mail at jonathan.watson@yahoo.co.uk