Asia: Panama Papers – no news is good news

Stephen Mulrenan

A third of all Mossack Fonseca’s business originated from its offices in Hong Kong and China. Local media coverage of the leaks has been inconsistent and, in some cases, actively censored by authorities fearing the consequences of these and further revelations.

More than $6tn flowed illicitly out of the developing world between 2002 and 2011, according to Washington, DC-based think tank Global Financial Integrity. Of this, over $1tn originated from China, making it the largest exporter of illicit capital in the world, ahead of Russia ($881bn) and Mexico ($462bn).

While China is not alone in suffering the consequences of illicit financial flows, its impact on the country is profound. The world’s shadow financial system has exacerbated inequality in China because much of the ill-gotten gains have eventually re-entered the country by way of foreign direct investment into speculative markets such as real estate. The British Virgin Islands ranks as the second largest foreign investor in mainland China, accounting for $10.5bn in 2010. As prices have surged, many of China’s middle class, working class and poor have been pushed out of their homes, while the government has been unable to collect tax revenues from the wealth.

Under President Xi Jinping, China recognised early on the dangers of such misconduct, which raises the cost of doing business in the country and slows its economic growth. In a speech in 2013, Xi warned that the continued misuse of public funds could even threaten the future of the Communist Party. ‘Many worms will disintegrate wood’, he cautioned.

It will make the Hong Kong authorities strengthen their supervision over the financial and legal industry, and may produce some preventive regulation’

Caroline Berube

HJM Asia Law & Co; Co-Chair of

IBA Asia Pacific Regional Forum

Given that China, as a member of the G20, participates in the multilateral automatic exchange of tax information programme, the reaction of Beijing to revelations from the Panama Papers has raised questions and concerns about everything from press freedom to the current state of the economy.

Documents from the hacked database of Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca confirmed that many Chinese companies and individuals have used anonymous shell companies in offshore tax havens such as the BVI for years. Notably, relatives of three of the seven members of the Communist Party’s elite ruling council, the Politburo Standing Committee, were shown to have companies that were clients of Mossack Fonseca.

Media block

While there is currently no suggestion of wrongdoing on the part of any of the Chinese names found in the leaked documents, a Communist Party censorship directive instructed news organisations to ‘self-inspect and delete all content related to the “Panama Papers” leak’.

Shanghai-based Co-Chair of the IBA Asia Pacific Regional Forum, and partner at HJM Asia Law & Co, Caroline Berube confirms:

‘We cannot find any information on the Panama Papers from the public media in China as the Chinese government has blocked it.’

While local media outlets were ordered to purge all reports relating to the offshore secrets of China’s political elite, broadcasts by international media such as the BBC and CNN have also been blocked.

Robert Wyld, Co-Chair of the IBA Anti-Corruption Committee and partner at Johnson Winter & Slattery, believes the media clampdown is evidence of a real concern by the Chinese government of what else might be disclosed by the Panama Papers. ‘If indeed Chinese government officials, companies, state-owned enterprises and business leaders [in the country] have made use of otherwise legal structures to hide assets out of the reach or knowledge of the Chinese government,’ he says, ‘that is likely to be severely embarrassing to the current leadership.’

While a number of media outlets in China have sought to portray the Panama Papers as a Western conspiracy designed to destabilise President Xi and the Communist Party – particularly in light of the fact that few public officials in the US have so far been exposed for any wrongdoing – coverage of the revelations in Hong Kong has been inconsistent.

On 20 April, prominent local newspaper Ming Paodismissed chief editor Keung Kwok-yuen after he ran a front-page story detailing revelations from the leaks about Hong Kong celebrities, officials and businessmen. In contrast, Hong Kong’s leading English-language newspaper, the South China Morning Post– now owned by China’s richest man Jack Ma and his e-commerce company Alibaba Group – has devoted many column inches to the scandal.

Impact of the leaks

Shell companies incorporated through Mossack Fonseca’s Hong Kong and China offices accounted for 29 per cent of its active companies. Indeed, the law firm has no fewer than eight offices across China – more than any other country – so it perhaps comes as no surprise that Hong Kong and China have featured so heavily in the exposé. Hong Kong’s colonial past, together with its role as China’s gateway to the world, helps to explain the proliferation of shell company ownership by the Chinese.

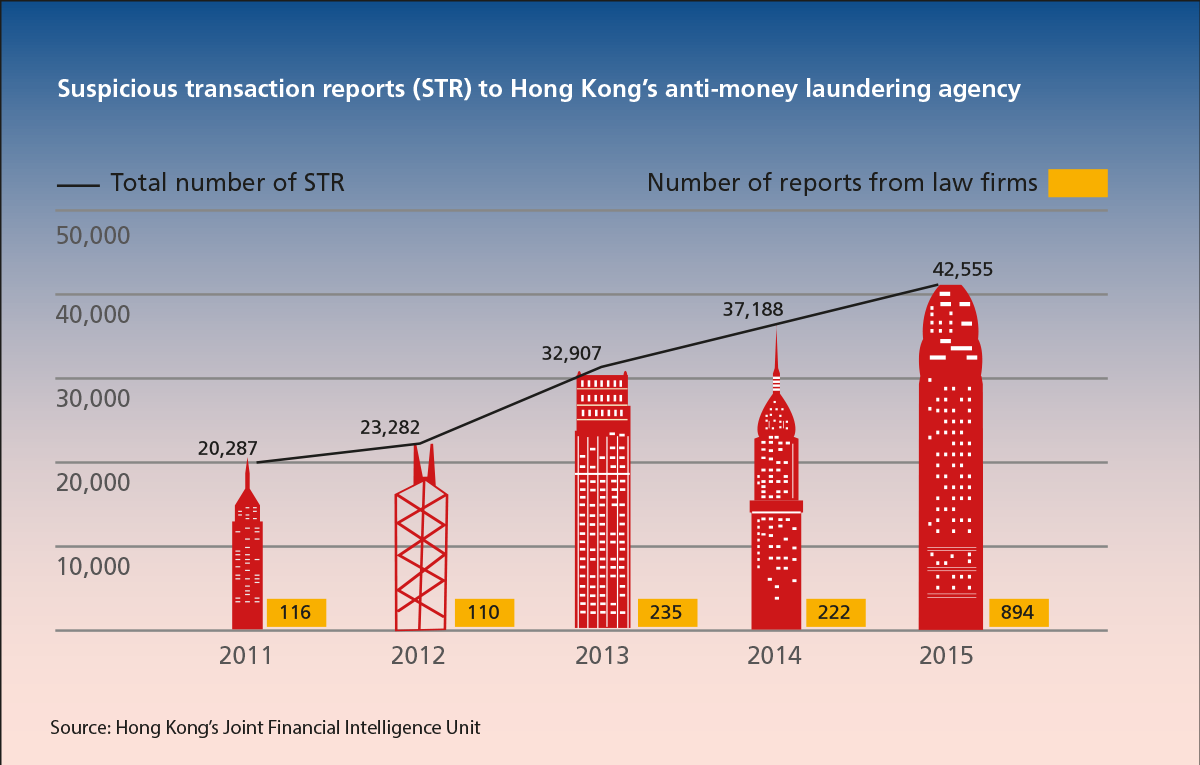

There has been much speculation in Hong Kong about the impact of the revelations on the city’s status as Asia’s most important financial hub. Even prior to the leak, the caseload of Hong Kong’s anti-money laundering agency had soared in light of a global crackdown (see box). This is largely due to Hong Kong’s anti-money laundering laws weighing in favour of prosecutors.

Commentators believe the Panama Papers are likely to make solicitors even more nervous, with reporting to the Joint Financial Intelligence Unit certain to escalate.

‘It will make the Hong Kong authorities strengthen their supervision over the financial and legal industry, and may produce some preventive regulation,’ says Berube.

Many shareholders of public companies in Hong Kong are offshore holding companies, and Wyld says there is also likely to be an increased international push to make lawyers and law firms ‘entities’ for reporting purposes, in terms of establishing the beneficial owners of complex, opaque structures. ‘This will make disclosure of the identity of the owners that much more transparent, and the flow of money across jurisdictions that much easier to identify for authorities,’ he explains.

The fact that many clients of Mossack Fonseca were domiciled in Hong Kong and China and sought a tax-effective or a foreign corporate structure outside those jurisdictions is not itself an issue if the source of the funds is legal and no illegal use occurred. Wyld explains that it becomes a serious matter when the purpose is to hide funds from authorities in particular jurisdictions, or to launder funds or seek to hide the proceeds of other illegal transactions.

Anti-corruption drive

In response to the documents leaked to date, international tax authorities and other agencies are expected to better coordinate to identify ‘stolen’ or ‘illegal’ assets that are transferred to other countries through structures that are legally created but used for illegal purposes, and to apply criminal law when seeking to restrain and repatriate funds more effectively.

There have been calls for the Chinese government to create a public registry of corporate beneficial ownership information, mirroring a commitment made recently by the UK.

But while the Panama Papers revelations are expected to have regulatory repercussions in Hong Kong, the consequences could be far more serious in mainland China. Beijing fears that further disclosures about the wealth of China’s political elite could spark public anger.

According to Wyld, if any of the assets documented in the Panama Papers prove to be illicit or illegally obtained, that will put great pressure on the Chinese government to act through its ongoing ‘Skynet’ and ‘Foxhunt’ anti-corruption operations. That will mean working with national agencies in relevant jurisdictions to restrain and seize assets, as well as applying for the extradition of Chinese nationals who have left China and are involved in holding the assets, and dealing locally with those still in the country.

‘And if that means targeting elite members of the political or business circle, that may well be the price the Chinese government has to pay to be consistent with its anti-corruption campaign,’ concludes Wyld. ‘The government has not shied away from this in the past, so the next six months will make for fascinating watching in this space.’

Stephen Mulrenan is managing editor of Compliance Insider at Compliance Publishing Group. He can be contacted at stephen.mulrenan@complianceinsider.com