The extraordinary journey towards justice in Africa

Ruth Green

Twenty-six years after he was ousted, Chadian dictator Hissène Habré was finally brought to account in May 2016. Global Insight examines the remarkable events leading up to the trial and assesses what the verdict means for international criminal justice in Africa and further afield.

The significance of Judge Gbertao Kam’s verdict in the landmark trial of Hissène Habré on 30 May 2016 was felt far beyond the confines of the courtroom of the Extraordinary African Chambers in Dakar, Senegal. Some 3,000 miles away in Chad, there was rejoicing in the streets, as the man whose government killed 40,000 civilians and tortured a further 200,000 from 1982–1990 was finally brought to justice.

During the 56-day trial, testimony was heard from 69 victims, 23 witnesses and ten expert witnesses, leaving no shadow of a doubt that Habré was guilty of crimes against humanity, war crimes and torture, including having personally committed rape during his time in power. Hailed as a victory for international justice, the verdict also raises questions – as well as shedding new light – on the ability of international courts, including the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague, to bring perpetrators of atrocity crimes to account.

Justice Richard Goldstone, Honorary President of the IBA’s Human Rights Institute (IBAHRI), says the circumstances leading up to the trial made the verdict all the more extraordinary. ‘This is a big win for international justice, a big win for victims and it’s a win too I think for Africa,’ says the South African international jurist. ‘It was the patient victims who waited more than two decades and who pushed, with the able assistance particularly of Human Rights Watch, for the Hissène Habré trial in Senegal.’

Historic day for Africa

Fatou Bensouda, the ICC’s Chief Prosecutor, agrees that the role of the victims in pursuing justice was crucial to making this a milestone for justice in Africa. ‘This was an historic day for the countless victims who have relentlessly – and I emphasise relentlessly – pursued and longed for justice for the victims of the crimes that have been committed in Chad,’ she told Global Insight. ‘And as an African and a person who is firmly committed to the cause of international criminal justice in the continent and beyond, I consider this verdict an important achievement in the fight against impunity for atrocity crimes.’

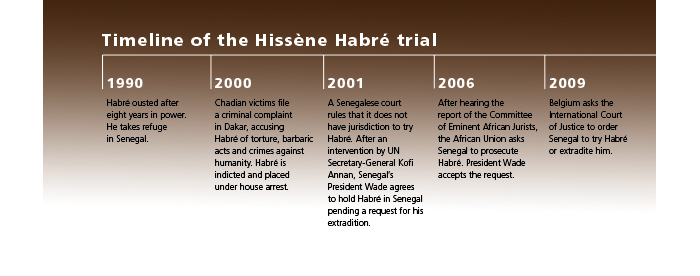

As well as the victims, several other parties were crucial in finally putting Habré in the dock 26 years after he was ousted and fled to Senegal – the reason he was tried in Dakar rather than his native Chad. ‘And of course what also drove it was the Belgian application for the extradition of Habré – they wanted to put him on trial,’ says Goldstone. ‘It’s also significant that the African Union stepped in – they didn’t want another African being tried in Europe, whether by an international or domestic court, and it was the AU that passed the resolution that pushed Senegal into setting up the Extraordinary Chambers in Dakar.

‘What also helped of course was that the International Court of Justice gave an order telling Senegal either to try Habré or to send him to Belgium,’ Goldstone continues. ‘So it was really a combination of all of these events and pressures. Each of them was extraordinary and each of them added up to the Hissène Habré trial in Senegal.’

Mark Ellis, Executive Director of the IBA, views the verdict as proof that justice will always prevail. ‘One of the most important aspects about these trials is reinforcing the idea that accountability will and should always trump impunity,’ he says. ‘For these types of international crimes there is no

statute of limitations.

This is a big win for international justice, a big win for victims and it’s a win too I think for Africa

Justice Richard Goldstone

Honorary President, IBA Human Rights Institute

‘In many ways that’s what this decision is about. If you look at when he committed those crimes, it was back in the ‘80s and early ‘90s. And yet impunity did not hold. Eventually he was brought to justice and that’s a very powerful message for any despot or any individual who has committed these types of crimes.’

This was a unique trial in many respects, not least because it was the first time that any state had tried the head of state of another country. The AU’s involvement was also particularly significant. ‘At a time when there are all these debates about the ICC and Africa and international justice, this is a trial that was supported by the AU and took place in one African country trying the leader of another African country,’ says Simon Adams, Executive Director of the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect in New York.

Heightened tensions

Tensions between the AU and the ICC have grown steadily in recent years. In July 2009, the AU ceased cooperation with the ICC, refusing to recognise the court’s moves to indict Sudan’s President Omar al-Bashir for war crimes and crimes against humanity. Many of the AU’s members, including Chad’s incumbent President Idriss Déby – the same man who toppled Habré in 1990 – have voiced criticism that the court focuses too much on African leaders since ten of the 11 investigations to date have involved African nations.

‘The Habré trial is not in any way going to alleviate the attitude of the AU and some African states towards the ICC, but it is an important recognition of the importance of stopping impunity,’ says Goldstone. ‘I’m not really optimistic about the AU fundamentally changing its attitude and pushing for an African regional criminal court – which incidentally I don’t oppose at all – but I don’t believe that there’s the political will, and even more importantly, I don’t believe there’s the money to do that.’

Sternford Moyo, former President of the Law Society of Zimbabwe and Chair of the IBA African Regional Forum, also doubts the trial will prompt the AU to go through with its threat of withdrawing from the ICC. ‘It is impossible to predict the impact of the Habré verdict on African leaders’ attitude toward international criminal justice and the International Criminal Court,’ he says. ‘In large numbers, African countries ratified the Rome Treaty. When the treaty opened for ratifications, no less than 31 African countries ratified it. It is illogical in the circumstances to then turn around and attack the court as being a western imposition.’

As an African and a person who is firmly committed to the cause of international criminal justice in the continent and beyond, I consider this verdict an important achievement in the fight against impunity for atrocity crimes

Fatou Bensouda

Chief Prosecutor, International Criminal Court

Critics of the ICC point to its lack of law enforcement staff on the ground to carry out evidence-gathering and what can often be lengthy delays in judges delivering verdicts. But the AU’s main criticism focuses on what it alleges as the court’s African bias, which fails to acknowledge that the court is restricted by its jurisdiction and that many of the cases have been referred by African states themselves.

‘The charge arose after four of the first situations to be dealt with by the court turned out to be cases from Africa,’ Moyo says. ‘The heads of state ignored the following factors: the Ugandan situation was referred to the court by President Museveni; the DRC situation was referred to the court by President Kabila; and the situation in the Sudan arose from a UN Security Council Resolution.

‘In all the circumstances, it would be idle to predict what the African heads of state are likely to do as a consequence of the verdict because the prediction would be based on a giant assumption that their position is held in good faith and is a result of a rational process. It is not.’

An African alternative to the ICC

But has this unique trial in Senegal called into question whether this type of ad hoc tribunal in Africa could provide a very real, viable alternative to the ICC in bringing accountability across the continent? ‘Justice delivered within a national context is more effective than that provided from an external source detached from the society over which it is exercising jurisdiction,’ says Steven Kay QC, a barrister at 9 Bedford Row and Co-Chair of the IBA War Crimes Committee. ‘It is without doubt that the real truth of events that have taken place is found within the state itself and not outside its borders. The people within are also better judges of the quality of the justice that has been delivered in their name. The quality of the trials at the ICC supports these propositions.’

Ellis says the real challenge lies in ensuring the trial process and proceedings meet international standards. ‘I’m a big supporter of these domestic trials,’ he says. ‘I’ve always felt that national prosecution is absolutely the most desirable solution that you could have, so long as – and this is the real issue here – you ensure that the domestic trial and the domestic proceedings meet international standards of fairness and impartiality.

That is absolutely essential if you are to show legitimacy for the proceedings.

‘It’s difficult even in the best of circumstances, but to do so in environments where the conflict may have just ended or where there is not sufficient background or knowledge becomes very difficult. This is where the international community needs to step up and assist nation states that have a desire to undertake these types of trials. I expect there are some imperfections in the trial and there will be criticism, that’s understandable, but for a general framework this is a very good model in moving forward and it does suggest that it could work in

other situations.’

Gregory Kehoe, a partner at Greenberg Traurig and Co-Vice Chair of the IBA War Crimes Committee, believes the ICC plays an important role, but says there is also a time and a place for ad hoc trials. ‘Let’s put it this way: is the world a better place for having the ICC in existence? Absolutely,’ he says. ‘Having a law enforcement body to monitor conduct and to have a country that couldn’t try one of its own leaders for war crimes, but being able to send that person to the ICC for trial, certainly we’re a better place for having that capability.

‘That being said, are there instances where having ad hoc tribunals could be a more effective method to deal with the problem? The answer to that is, of course, yes. I think we’re seeing some discussion about that in relation to Syria. We have an instance for example in Lebanon where you have some Lebanese judges and some international judges working together in a hybrid system where the individual jurisdiction can operate equally with the international community in a court system. There are a variety of different methods, but I don’t think we’re done with ad hoc tribunals in any sense of the word.’

At a time when there are all these debates about the ICC and Africa and international justice, this is a trial that was supported by the AU and took place in one African country trying the leader of another

Simon Adams

Executive Director, Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect

Moyo agrees that the ICC, established in 2002, continues to provide an alternative judicial forum when domestic justice is severely lacking. ‘The court exercises complementary jurisdiction,’ he says. ‘It does not get involved where the state whose situation is being referred to it is willing and able to prosecute. The court does not discourage domestic prosecutions. It only comes into the picture in situations where the domestic mechanisms cannot provide justice.’

Adams stresses that the verdict in no way diminishes the ICC’s role as an international judicial mechanism. ‘I’m a supporter of the ICC,’ he says. ‘That’s not to say that I don’t think it’s made mistakes, but in general I’m definitely a supporter of the ICC and I think the current prosecutor is doing a very good job in very difficult circumstances.

These cases are victories for international justice – that’s the real significance.

‘The other thing is that the ICC should always be a court of last resort and it was only ever intended to be a court of last resort,’ Adams continues. ‘In a perfect world no cases should end up at the ICC because they would be dealt with in a domestic jurisdiction or they would be dealt with by a regional tribunal or other judicial mechanism. They would be dealt with in one of those fora and they wouldn’t need to end up at the ICC. I think this was clearly the appropriate forum for him to be held to account and it was done very successfully and I absolutely applaud

the judgment.’

Support for Senegal

Speaking to Global Insightshortly after the Habré verdict, Bensouda praised the proceedings and the parties involved in bringing Habré to trial. ‘I remain supportive of all efforts that are taking place, whether in Africa or elsewhere, to ensure that perpetrators of these crimes will be held accountable,’ she says. ‘This is what we are doing and of course the ICC doesn’t have monopoly over trying all these crimes wherever they take place.

‘The effort that has been made at the AU level together with Senegal, more or less giving Senegal the mandate to try these crimes, and other partners helping in this effort is to be commended – this is what should happen. We have vowed as an international community that there will no longer be impunity for these crimes so we should try to live up to that.’

Rather than negating the ICC’s work, Bensouda believes such ad hoc trials vindicate the work the ICC and other courts are doing to bring justice to victims worldwide. ‘Regarding Hissène Habré, the crimes took place even before the ICC was established, so we do not have jurisdiction,’ she says. ‘It only goes to show that it is important that we have justice for these atrocity crimes when they occur, especially where the ICC does not have jurisdiction and an effort has now been made at the continent level to ensure that there is a trial, accountability and there is finally justice for the victims of these crimes.

‘If there are efforts to bring to justice those who commit those crimes at the national level they should be commended for that because they are doing their duty and their responsibility. So this cannot be a bad thing. What is bad, I believe, is that these crimes continue to be committed and there is [often] no form of accountability whether at the national level or the regional level. This is not what we should be doing. We should be encouraging accountability.’

The ICC recently handed down an

18-year sentence to Jean-Pierre Bemba, former Vice-President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, for murder, rape and pillage committed by his troops in the Central African Republic from 2002–2003. Bemba is the highest-level official ever to be convicted at the ICC and the case marks the first time that the ICC has focused on rape as a weapon of war – a subject about which Bensouda feels strongly. ‘I want to highlight the importance that I attach to ending impunity for sexual and gender-based crimes,’ she says.

‘Also the plight of victims of atrocity crimes is undoubtedly one of the pillars of our work at the ICC. The court was created to give a voice to victims, to be able to deter atrocity crimes and thereby protecting future generations from falling victim to these egregious crimes.’

As with the Habré case, Bensouda hopes the Bemba trial will send a resounding message. ‘I believe this trial and the sentence that has been imposed on Mr Bemba sends a very clear message to anyone in a command and control position, that they are responsible for the actions of the forces that are under their control and no matter where those troops operate they have as commanders a legal obligation to ensure that their troops don’t commit crimes under the jurisdiction of the court and, if they do, to investigate and

punish them.’

As for the Habré trial, Kehoe believes it will have particular resonance for military leaders across the world. ‘I can tell you that cases that emanated from the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia concerning the use of military units, those decisions are studied routinely by armies throughout the world as a way to operate and ensure that their troops are operating within the law,’ he says. ‘So yes, it does have an effect and an impact. I do think that much of that impact is difficult to gauge, but I can tell you from having been in military settings these decisions are discussed and people do pay attention to them.

‘A clear stand has been made that if a leader engages in this kind of conduct directed against the innocent civilian population then he will be brought to book. Time is not just going to cause the international community to overlook these horrific events.’

Professor Philippe Sands QC, a barrister at Matrix Chambers in London, agrees that history has taught us that such people will be brought to account, no matter how much time has elapsed. ‘To understand the Hissène Habré trial and the concept of trying people for genocide you need to go back to the Nuremberg trials,’ he says. The Nuremberg trials in the 1940s marked the first time that national leaders had been indicted for war crimes before an international court, a topic Sands covers in his recent book East West Street: On the Origins of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity.

‘It shows us that 70 years on the legacy of the Nuremberg judgment still continues,’ adds Sands. ‘I think to understand what is going on now, you have to understand the origins of the international justice system, have an understanding of the historical sense of these trials and the involvement of crucial individuals. What they all show is that you can’t ignore history.’

Ruth Green is Multimedia Journalist at the IBA and can be contacted at ruth.green@int-bar.org