The hundred-billion-dollar hotel

Tom Bangay

Airbnb started as a home-sharing scheme in San Francisco, but is now an international travel giant, with rumours of a lucrative IPO. Global Insight assesses its meteoric rise and whether more can and should be done – by the company and regulators – to mitigate the effects.

When the founders of home-sharing website Airbnb were starting out in 2008, they soon ran out of money. The enterprising founders, Brian Chesky, Joe Gebbia and Nathan Blecharczyk, sold special ‘Obama Os’ and ‘Cap’n McCains’ cereals for $40 a box to raise funding for the company’s incubation. Those days are long gone for what is now a funding juggernaut – from $7.2m series A funding in 2010, Airbnb has raised huge sums, escalating through $112m in 2011, $475m in 2014, $1.5bn in 2015 and a reported $850m in 2016, the year it began to turn a profit. Its latest funding round in 2017 indicates a potential valuation of up to $31bn. Airbnb has more than 3,000 employees, three million listings in 65,000 cities and more than 200 million users.

Growth at such speed, in a sector as complex and heavily regulated as the hotel industry, has not gone unchallenged. Arun Sundararajan, Professor of Business and the Robert L and Dale Atkins Rosen Faculty Fellow at New York University’s Stern School of Business, is the author of The Sharing Economy and has analysed Airbnb’s impact, including an in-depth study on New York. ‘The service that Airbnb is disrupting is historically regulated at a local level, unlike other industries that have been disrupted digitally like broadcast television, telephony and news,’ Sundararajan says. ‘The emergence of Airbnb has necessitated a close look at how both hotels and residential real estate are regulated, and has highlighted the need for us to expand regulatory frameworks to accommodate what is offered through a platform like Airbnb.’

Residents of cities with high Airbnb usage have complained of property damage, excess noise and deterioration of community cohesion, all of which Airbnb has tried to address. However, perhaps the most serious concern is that Airbnb empties districts of permanent residents. David Jacoby is former Chair of the IBA’s Leisure Industries Section and a partner at Culhane Meadows, New York. ‘People are not just renting out the one place they live,’ he says, ‘they’re buying properties just to rent them out, causing ripple effects and impacting house prices.’

Concerns that a professional class of hosts are making money from the platform, while affecting housing stock and rental costs, have followed Airbnb since its inception, particularly in its hometown of San Francisco, where growing vacancy rates have accompanied an average monthly rent of over $3,900 and average home prices of $1.1m. Similar concerns have been voiced regarding cities as diverse as Amsterdam, Barcelona, Florence, London, and Paris.

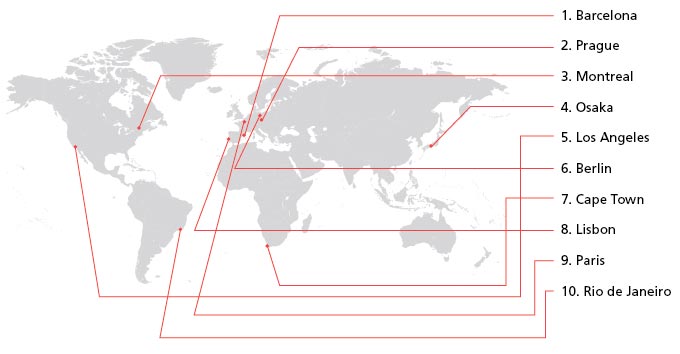

Airbnb by the numbers (figures as of 2018)

An unrealistic burden

The issue is how authorities regulate a provider that competes with the largest hotel chains in the world, yet owns almost no property. ‘Government regulatory systems are typically set up expecting a few modest-sized business and professional providers on the other end,’ says Sundararajan. ‘With Airbnb, you could end up with hundreds of thousands of tiny hoteliers in a city like New York – an unrealistic burden for government to shoulder alone.’

In the United States, everyone from the Federal Government, State Government, City Hall and building administrators, down to a local co-op board, might have a say in regulating short-term accommodation. Conversely, in a different jurisdiction, the affected regulators might be completely different, and Airbnb hosts might avoid the scrutiny and taxation requirements with which hotels must comply, for example. Tom Copley is the London Assembly Member and Housing Spokesperson. ‘Hotels also see it as unfair competition,’ he says. ‘Hotels have to observe hundreds of different regulations, whereas hosts on Airbnb aren’t held to the same standards.’

While Airbnb brings obvious benefits for tourism, cities around the world have responded in various ways to the challenge it presents to housing costs, community cohesion and regulatory standards. France is Airbnb’s second-largest listings market outside the US. Its impact in Paris – a city already flooded with tourists – is keenly felt, says Emmanuelle Llop, Europe Regional Representative for the IBA Leisure Industries Section. ‘Paris tries to regulate these rentals but it does not seem to be very efficient: the centre of the city is more and more empty,’ says Llop. For example, the first four districts are soon going to be gathered into one administrative district, because there are so few residents. The Mayor of Paris, Anne Hidalgo, plans to combine four of Paris’ historic arrondissements in 2020. The city has also introduced a 120-day limit on how many nights hosts can rent apartments for in districts 1 to 4, supported by Airbnb, who introduced a ‘ticker’ on hosts’ listings pages on the site.

Barcelona requires listed apartments to be licensed, threatening unlicensed hosts with e60,000 fines, against a backdrop of local rents up 23 per cent in three years. Amsterdam went further, preventing homes from being listed for more than 60 nights per year. The city’s executive board plans to halve that period to 30 days. Amsterdam housing alderman, Laurens Ivens, said ‘I recognize that reducing the length of time [permissible to host on Airbnb] is not the solution to city congestion, but it will reduce the problems caused by tourists in some areas, and will make it less inviting to use your home as a way to earn money.’ Critics of such moves ask why private citizens shouldn’t use their homes to generate income.

A protest banner hangs from a balcony in Barceloneta neighborhood in Barcelona, Spain. The banner reads ‘No tourists apartments’. © REUTERS/Albert Gea

Hotels meet the housing crisis

London is confronting digital disruptors on numerous fronts at the moment, with ride-sharing app Uber facing a ban after its appeal. However, Airbnb has been adopted with less controversy by much of the capital’s population. ‘There are some boroughs in outer London that see Airbnb as a benefit to their local economies, with people staying there instead of in central London. This helps people with the cost of living if they can rent a room in their home, or the whole property if they’re on holiday,’ says Copley. ‘That’s the sharing economy, and that’s what Airbnb was originally designed for. The problem is a professionalised sector of Airbnb hosts taking property off the long-term rental market, and into short-term lets – we already have a housing crisis in London, and that’s taking away properties that could be rented long-term.’

London responded by introducing specific legislation limiting entire home listings to 90 days a year, although enforcement is a challenge. ‘The limit is enforced by boroughs, but the boroughs find it hard to know whether that limit has been reached. Airbnb led the way by enforcing the limit on their site if people haven’t provided evidence of the planning permission required to rent beyond 90 days – other platforms haven’t,’ says Copley. Other home-sharing sites are ready to profit from any limitations Airbnb places on itself. ‘Although Airbnb has helped, that doesn’t stop people jumping from platform to platform for 90 days at a time. We need platforms to share their data with local authorities so they can see how many days hosts have rented their properties for, and then take enforcement action against them if they have violated planning rules. This can mean a fine of up to £20,000.’

The emergence of Airbnb has necessitated a close look at how both hotels and residential real estate are regulated, and has highlighted the need for us to expand regulatory frameworks

Arun Sundararaja

Professor of Business, New York University

New York City is one of the world’s most expensive, and lucrative, hotel markets, creating an environment ripe for Airbnb to thrive. Its use sits at the heart of a web of regulatory interests. ‘The issue intersects with regulating tourism, affordable housing, zoning, commercial use of personal space – it’s a regulatory “mosh-pit”,’ says Sundararajan. New York State’s Multiple Dwelling Law, which covers buildings with three or more units, prohibits short-term rentals of fewer than 30 days at a time, unless the owner is present for the time a guest is renting.

The findings of Sundararajan’s research – Airbnb Usage Across New York City Neighborhoods: Geographic Patterns and Regulatory Implications – were unexpected. ‘It was surprising to find not just that the use of Airbnb was moving out and away from higher-income neighbourhoods, but that this was happening in parallel with a shift away from hosts renting out entire apartments and instead renting single rooms.’

People are not just renting out the one place they live – they’re buying properties just to rent them out, causing ripple effects and impacting house prices

David Jacoby

Former Chair, IBA Leisure Industries Section

And, while the proliferation of professional hosts is an oft-cited concern, the numbers just didn’t add up. ‘I’ve often heard the concern that people are taking units off the market and running them as Airbnbs – that seems highly unlikely in New York City, as you have to host over 200 days on average to break even’; 216 days was the precise point at which hosts would cover their running costs, on average, versus a typical tenancy. This suggests a pattern of Airbnb usage which, whether a result of New York State’s limitations or not, stops short of professionalised landlords monopolising housing.

Enforcement on a global scale

Airbnb’s willingness to pre-empt regulatory difficulties and engage with authorities is admirable, particularly in comparison to other large-scale disruptors. ‘Airbnb has been much better at communicating with regulators and doing voluntary enforcement,’ says Copley. ‘Uber has been much more adversarial. Airbnb and I don’t always agree, but they do go out of their way to try to address concerns.’ Nevertheless, the ability to enforce any code of conduct changes remains unclear. As Jacoby points out, ‘with three million rooms, they don’t have the enforcement mechanisms versus their scale to apply any regulations they introduce, and if they did, it might change the economic model so as to be unsustainable.’

In Paris, meanwhile, Llop says things are less straightforward. ‘Airbnb is not bound by our Tourism Code, but by digital and distance sales regulations,’ she says. ‘Airbnb presents clear unfair competition to hotels, as it not only works on a business-to-consumer basis, but also with travel agencies, for example.’ Traditional providers all submit to regulatory requirements that Airbnb hosts have, as yet, largely managed to avoid.

Past remedies might provide a way forward. In the platform’s early days, stories of trashed apartments and wild parties attracted bad press for Airbnb. ‘They set up insurance policies, which largely seem to have addressed that problem,’ says Jacoby. Could Airbnb build on that insurance model to mitigate wider damage to communities and pricing? This may be unrealistic, given Airbnb is not the only home-sharing platform around: ‘If restrictions came from Airbnb, and the platform limited itself in that way, a competitor would only respond and fill the gap,’ Jacoby points out.

Airbnb itself could be seen as a symptom of rising housing costs. ‘Many of the cities in which people have raised concerns that Airbnb is contributing to a shortage of affordable housing are also cities with other factors influencing that supply,’ says Sundararajan. Hosts may be turning to Airbnb to help with house prices and rents that were rising long before three San Francisco entrepreneurs started selling political cereal. ‘For example, in New York City and San Francisco, population growth has been significantly higher than was projected. Both of those cities have a significant fraction of rent-controlled or rent-stabilised housing stock.’ A demand shock to the remaining supply leaves a smaller proportion that can respond: ‘Even a modest increase in demand can cause a significant increase in prices.

Rent stabilisation and population growth are much greater contributing factors for rising prices in long-term rentals in those cities,’ Sundararajan explains. While London can’t blame Airbnb for the disconnect between its sky-high housing costs and the rest of the country, it certainly isn’t helping. ‘At the macro level, I think the impact on prices is marginal,’ says Copley, ‘but that doesn’t mean it won’t become an issue in the future. Taking Florence as an example, that city already has a problem with “over-tourism”, and when you add in Airbnb’s contribution, as much as 15 per cent of housing stock is on Airbnb there (certainly in the centre). If action isn’t taken to try and stem that, you could find that situation here, with a much larger proportion of housing stock taken up by short-term lets.’

Rewarding rents

The most lucrative cities in which to rent properties on Airbnb, according to Airdna, a company that tracks Airbnb rental data and performance.

Rooms for refugees

While Airbnb’s eye-catching funding and rapacious growth bring negative headlines, its supporters can point to investments and initiatives that show the platform in a much more flattering and responsible light. Last year, Airbnb acquired the startup Accomable, a site that connects its users with accommodation friendly to disabled people. At the time of the acquisition, the small team at Accomable could only serve five to ten per cent of the booking requests they received; Airbnb’s firepower, in terms of infrastructure and headcount, could help deliver an invaluable service to a global user base.

Similarly, Airbnb launched its Open Homes project in June 2017, formalising a long-running effort to offer housing to displaced people and refugees. Not-for-profit organisations and relief worker agencies make bookings and pay no fees. Some 6,000 listings globally are set at a $0 fee, primarily in the US and Europe, targeting refugees, disaster relief, medical needs and the homeless. Open Homes grew from the platform’s response to President Trump’s travel ban aimed at seven Muslim-majority countries. Chief Executive Officer Brian Chesky was publicly critical of the policy and mobilised Airbnb to support travellers stranded by the ban.

IPO rumours persist

The size, profile and valuations of Airbnb have prompted conjecture as to whether the company might go public. Its most recent funding round suggested a valuation of some $31bn. Compared with the biggest global hotel chains, for example, this would put the company second only to Marriott.

‘$30bn is a fairly modest figure, given the reach of the company and what I expect its market power to be in the future,’ says Sundararajan. ‘Its scale is already pretty immense – if you stop thinking of Airbnb as a platform and think of them as a next-generation, digitally enabled franchising organisation – albeit a hands-off one – the scale is huge: the number of people staying in an Airbnb on New Year’s Eve 2017 were, by my estimates, more than Marriott and Hilton combined.’ Airbnb is still growing, with recent strategic acquisitions aimed at adding two million more listings in Asia. ‘I see no reason why they wouldn’t be significantly more profitable than the largest players in the world – if it’s going to be the global platform for travel, I could see it having a valuation of $100bn or more in the not too distant future,’ says Sundararajan.

Is there anything hotels can do to avoid being crushed under Airbnb’s wheels? ‘Airbnb isn’t going to go away so they are finding other ways to try and compete,’ says Jacoby. ‘Hotels have intrinsic advantages they should try to exploit – gyms and spas, suites, bigger rooms, restaurants on site, security, privacy. The appeal of many hotel chains is predictability – that’s harder for a service like Airbnb to emulate,’ he points out. While Airbnb may be primed to take its position alongside Google, Amazon and Facebook as the tech titan to rule travel, there will always be a place for the traditional hotel – but they may have to adapt to survive.

Tom Bangay is a freelance journalist and can be contacted at thomas.bangay@gmail.com