No 1,067: the long wait for asylum in the United States

Alice Driver, Mexico

When Kirenia Navas Rodríguez fled political persecution in Cuba, her year-long journey saw her cross 11 countries, taking enormous risks. Now, at the US–Mexico border, she is confronted with the Trump administration’s asylum policy.

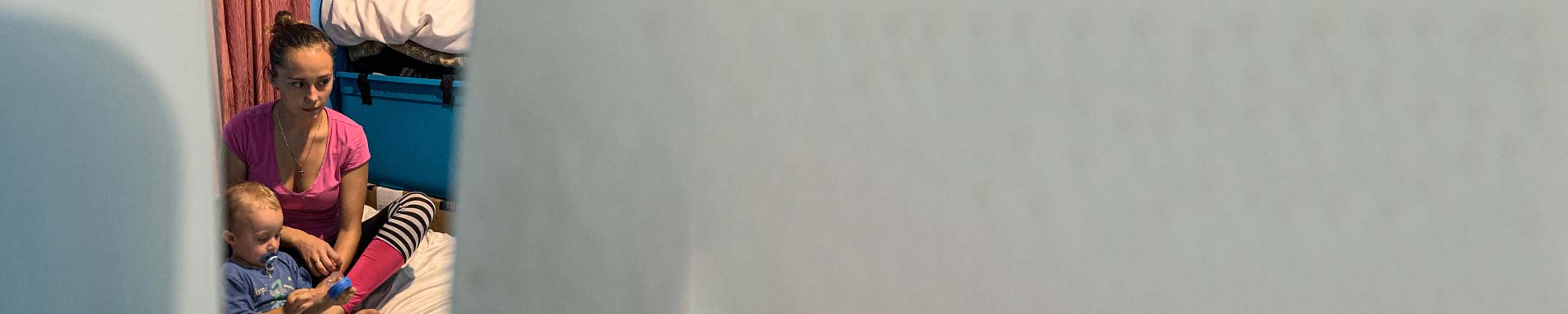

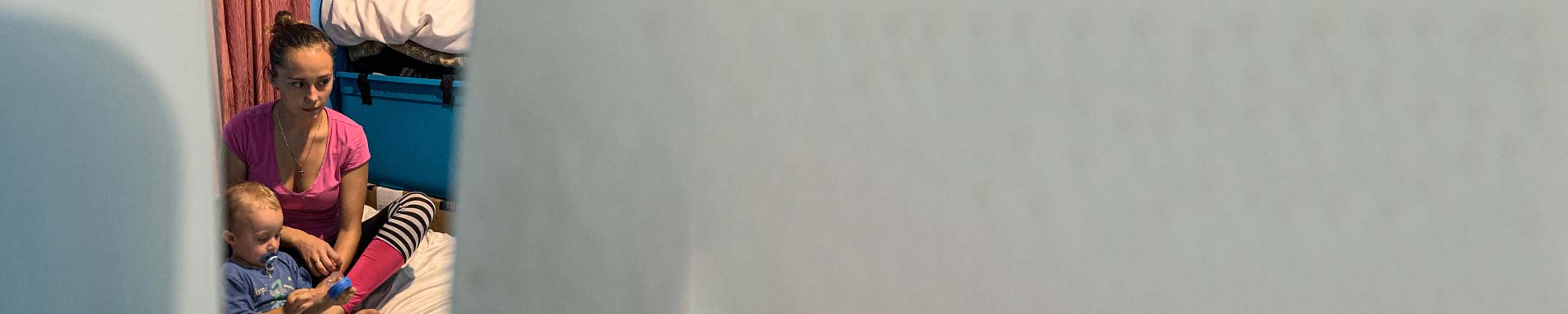

At dusk, a young woman sweeps and washes down the concrete outside her tent. The ritual is one carried out across Latin America, where people wash the doorstep and pavement area in front of their homes. Kirenia Navas Rodríguez, 26, and her partner, Lazaro Franco Rodríguez, 24, fled political persecution in Cuba. Now, the tent behind her is their home while they wait to request asylum in the US.

The couple’s journey to the border took almost a year: they flew to Guyana, traversed the Amazon rainforest, arrived in Brazil without any money, worked illegally for six months and then travelled through Peru, Ecuador, Colombia and the Darién Gap. They crossed 11 countries before arriving in Matamoros, Mexico, at the US–Mexico border on 15 April 2019.

The pair spent May living in a camp next to one of the international bridges in Matamoros, alongside hundreds of other asylum seekers. There, they learned to navigate a series of changes in US asylum policy under the Trump administration, including ‘metering’, in which asylum seekers are required to spend weeks or months living in dangerous border areas in Mexico to be able to request asylum in the US.

The border is being progressively restricted so that there are fewer entry points, longer waits, less appointments, and so it takes longer and longer to get through

Jacqueline Bhabha

Professor, Harvard School of Public Health

In each border town, the asylum waiting list process is different. In some cases, directors of migrant shelters or the migrants themselves help keep the numbered list organised. Every week, when US officials give permission to proceed, only a handful of numbers are called.

Jacqueline Bhabha, Professor of the Practice of Health and Human Rights at the Harvard School of Public Health, says the changes made to established asylum law are fundamental and extreme violations of basic protections that have long been established.

‘It is not just what is happening on this side of the border – it is happening on the other side of the border,’ she says. ‘Tens of thousands of people are being forced to wait out requests for asylum for months in dangerous border areas. The border is being progressively restricted so that there are fewer entry points, longer waits, less appointments, and so it takes longer and longer to get through.’

Migrants in Matamoros and Reynosa have been waiting an average of two months to be able to request asylum. Once US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) call their number on the waiting list, they will be taken to a point of entry to request asylum. Under the Trump administration’s newly implemented Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP), they will then be returned to Mexico for the duration of their immigration proceedings.

Navas Rodríguez and her partner were initially given numbers 1,067 and 1,068 on the asylum waiting list. Other migrants told them it could take six or seven months for them to request asylum. The couple heard about a shorter waiting list at another international bridge in Matamoros, so they moved their tent to sign up.

Rodríguez admits she has been depressed. ‘So many people are desperate that they have crossed the river illegally. We are drowning in desperation but we can’t throw in the towel. We are waiting our turn to request asylum.’

More asylum seekers arrive at the border every day, having survived significant violence and trauma. Often they have few financial resources. Those that have family in the US borrow money if they can to avoid life in the tents or on the street in dangerous border areas.

Waiting for weeks or months to request asylum as part of a process that is not clearly defined and has no specific timeline has driven some to desperate measures. Jenifer Castro, 24, from Honduras, paid a smuggler $3,000 per person to guide her and her two sons across the Rio Grande river. But the smuggler kidnapped them and held them ransom until she gave him more money.

In June, the harrowing photograph of Óscar Alberto Martínez Ramírez and his 23-month-old daughter, Valeria, from El Salvador, who drowned while trying to swim across the Rio Grande, told the world of the awful reality of the border conditions for vulnerable migrants.

In 2018, Attorney General Jeff Sessions issued a decision, Matter of A-B-, to limit asylum grants for those fleeing domestic and gang violence, a move that has had a marked impact on women migrants. Blaine Bookey, Legal Director at the Center for Gender and Refugee Studies, explains, ‘Some judges are relying on A-B- to deny asylum.’

Allegra Love is an attorney and Director of the Santa Fe Dreamers Project, which provides free legal services to immigrants. She says there is a particular impact of changing asylum policies on trans women. ‘Trans women need to come to the US. They are not safe in Mexico. What [the administration] are trying to do is chip away at how they can restrict asylum with enforcement. MPP is a big blow.’

Back in Reynosa, Areli García García, 28, and her eight-year-old son, Danilo, are living in a migrant shelter. García once sold tacos in Chiquimula, Guatemala, but fled the country in fear of domestic and gang violence, two issues that are often related. In May, having been on the waiting list to request asylum for over a month, she was at number 318 on the asylum list.

‘I am worried because I have gotten sick a lot here,’ García says. ‘The heat affects the children a lot.’ She hopes to be reunited with her mother, who has been living in Los Angeles for 23 years. Of the asylum waiting list, she says, ‘I wish the list was in order because sometimes many people get in front of us that haven’t been waiting here for 40 days.’

Every asylum seeker is a number. CBP requests asylum seekers based on criteria that varies, including calling for only pregnant women, single men, single women or families. For days or weeks, CBP might make no request for asylum seekers at all.

Those navigating the system quickly learn that their waiting list number means very little. Some carry pieces of paper showing a series of additions and subtractions that reflect their changing status – numbers they hope will eventually add up to an equation that allows them to request asylum.

Alice Driver is a freelance journalist and the author of More or Less Dead: Feminicide, Haunting, and the Ethics of Representation in Mexico. She can be contacted at alicel.driver@gmail.com

Photographs from Matamoros, Mexico, 2019 © Alice Driver