A conversation with Sir Bill Browder KCMG

Thursday 20 November 2025

Sir Bill Browder KCMG, Head of the Global Magnitsky Justice Campaign, speaks to IBA Executive Director Mark Ellis about the history of the Magnitsky Act, Putin’s position in Russia and the effect of sanctions.

Mark Ellis (ME): I'd like to start with the Magnitsky Act. Can you just bring us up to date a little bit on how that campaign is progressing?

Bill Browder (BB): The idea behind the Magnitsky Act is when a country like Russia acts with impunity and there's nothing you can do, as was the case with Sergei Magnitsky's murder, that you can hit the people who did that with something that they care about, which is going after their money offshore, freezing the assets and banning their travel. And it really was the Achilles heel of the Putin regime.

Putin reacted [angrily] to the Magnitsky Act being passed. He banned the adoption of Russian orphans by American families. He made repealing the Magnitsky Act his single largest foreign policy priority. And then he started coming after me with death threats, kidnapping threats, arrest warrants, extradition requests, everything. And so, we knew that we had, in the parlance of the game Battleship, a direct hit.

I knew it most of all in the summit between Trump and Putin in 2018, when it was right after Robert Mueller had indicted 12 Russian military intelligence officers for interfering in the US election. Putin met with Trump in Helsinki, and at the press conference, one of the journalists asked Putin, are you going to hand over the 12 GRU officers? And Putin said, yeah, it's possible we would do so, but we would expect goodwill and reciprocity from our American friends, and we would expect them to hand over Bill Browder. So, [Putin’s] next obvious question to Trump [was]: ‘Mr President, what do you think?’ And without skipping a beat, he said, ‘I think it's an incredible offer’. And it required a vote in the Senate four days later, 98 to zero, not to hand me over before the whole thing died a death.

I wanted all rule of law countries to have a Magnitsky Act

The reason I tell this story is because we know that the Magnitsky Act is a powerful tool. And so, I've spent the last [few years], since 2012 when it was passed, trying to get other countries to pass it. I wanted all rule of law countries to have a Magnitsky Act. And as I went around talking to governments, I discovered something, which is nobody wanted to follow the United States. And this is long before where we are right now, but nobody wanted to follow the United States. There's always been a certain amount of anti-Americanism in the world. And so I said, I need to get another country to do this that could then open the floodgates.

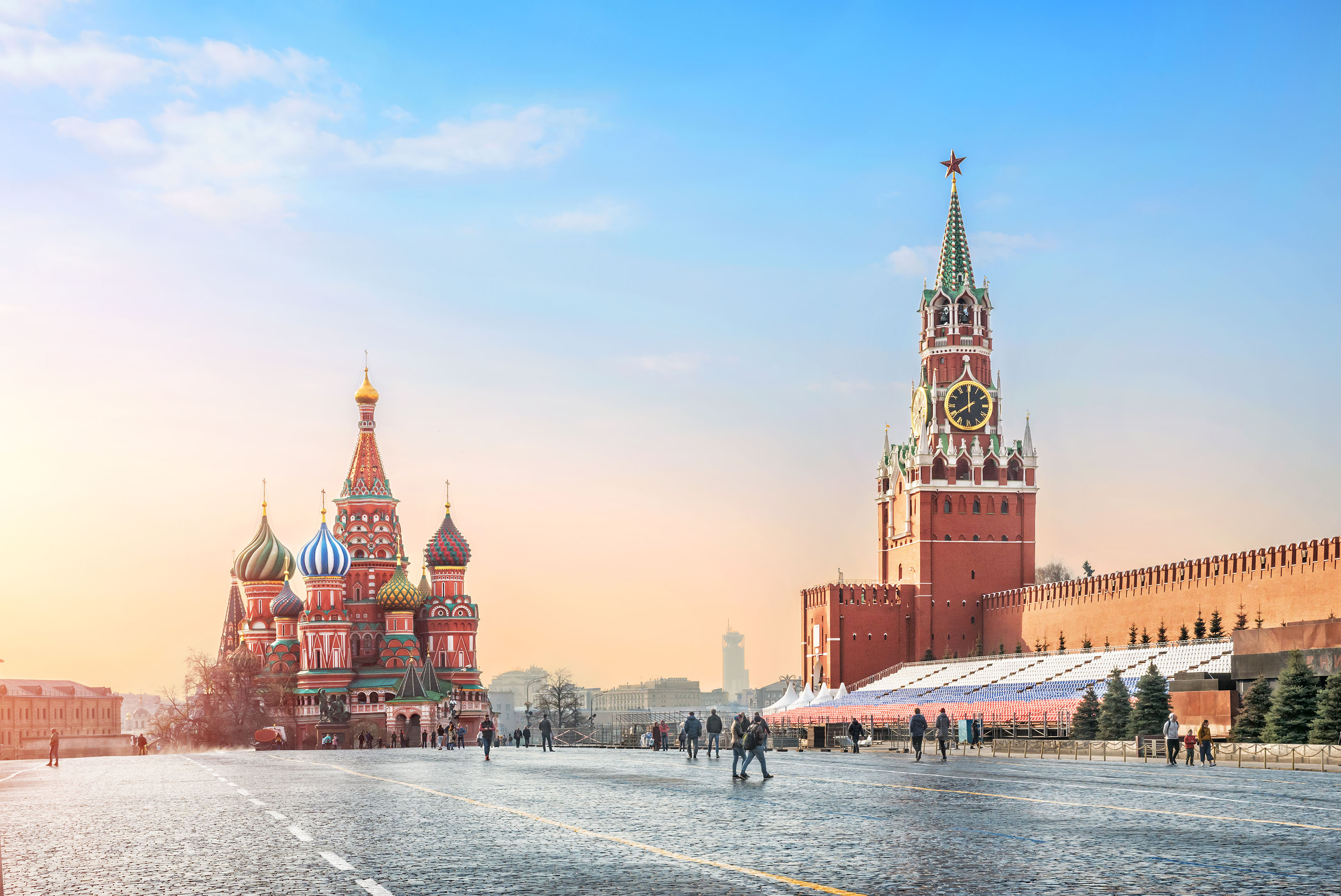

The Kremlin and Red Square in Russia, Moscow. Adobe Stock/yulenochekk

And my logic was that there might be a lot of anti-Americanism in the world. There's no such thing as being anti-Canadian. And we got the Canadian Magnitsky Act passed in 2017, and that was the domino that fell, and all the dominos started following it. After Canada, we got the UK, after the UK we got the EU, we got Australia. We got three Baltic countries within the EU to have their own Magnitsky Act, [then] the Czech Republic, Norway, Iceland, Montenegro, Kosovo. There [are] now 35 countries with Magnitsky Acts around the world, and it really has turned into something so much bigger than I could have ever imagined. It doesn't just apply to Russia; it applies to human rights abusers everywhere in the world. Victims from China, victims from Iran, victims from everywhere can now have a tool in most rule of law countries who have a Magnitsky Act.

People say to me, ‘OK, do you have enough countries with Magnitsky Acts?’ And I say, no, we're missing two. We're missing New Zealand, which doesn't have a Magnitsky Act, and we're missing Japan. I want to have rule of law countries.

As some of you will remember, Brazil had a previous president named [Jair] Bolsonaro, who tried to do the same thing in Brazil that Trump did on January 6th in the United States; he didn't want to give up power. And in Brazil, they actually prosecuted him, and the person in charge of the prosecution is a judge named Moraes. Donald Trump took a huge offence to this because he was friends with Bolsonaro and in something that truly makes me uncomfortable and really demoralised, I would say, the United States used the Global Magnitsky Act to sanction the judge who is prosecuting Bolsonaro.

We have a situation where this law, which was very much the work of my life to go after torturers, killers, death squad members, kleptocrats, was used to sanction a judge prosecuting in a legitimate prosecution against a corrupt politician. I don't think it ruins the Magnitsky Act, but it certainly has raised questions, which I feel very uncomfortable about.

ME: Could you give a sense of the effectiveness of sanctions on assets? Is that something that you have seen work?

BB: The big picture is that before the Magnitsky Act existed, the only sanctions that existed were sanctions on a whole country. And so, there's two problems with that. One, you sanction a whole country like Iran. Iran has done a lot of terrible things and we have sanctioned Iran long ago. But what happens is that the people of the country suffer and the elite, the ones who are doing all the terrible stuff that we get upset about, they're flying in planeloads of caviar and champagne and still living the same kind of life they had before. And so we kind of wanted to flip this whole thing on its head and say, let's forget about the country, let's go after the specific individuals that do the really bad stuff because when you name and shame somebody, whether it's assets or visas or anything, but if you name and shame them personally and individually, that has an effect.

Then, of course, I would say that 95 per cent of all human rights abuse and misgovernance and kleptocracy all surrounds money. Most people do bad stuff in their governments for money. And they don't keep that money in the country that they do the bad stuff in, they keep that money 'safe' in the West. And so, if you kind of take away the whole concept [that] they could do whatever they want in their own country and then they have this nest egg outside of the country, that really drives them up the wall. I mean, it's absolutely horrifying for them.

But what was interesting is that everybody was scared. Everybody thought, 'God, is this gonna come to me?' And so, part of the value of the Magnitsky Act is of course punishing the individuals doing the bad stuff, but it's creating a climate of fear around those individuals of who's next, and could you be added to the sanctions list?

ME: Do you still see corruption in Russia and Moscow? Is that still the glue that's holding things together in [Putin's] inner circle? Or have we moved to this kind of wartime nationalism that has replaced corruption?

BB: Well, corruption will always be the basis for everything that happens in Russia and I think it's really important to connect the corruption to the war, because it's really the cause of the war.

They're not laundering the Russian money anymore. That's all finished. The money that's stolen from Russia is sitting in the West. The money [that was] stolen from the Russian government should have been spent on hospitals, schools, roads, public services. Instead, it was spent on yachts, private jets, villas in the south of France by Putin and a thousand people around him. And the reason why that's so significant is that that is like emptying gasoline on the floor of Russia. And all it takes is one match to light it all up. If you have a thousand who have benefited and 145 million people that are living in destitute poverty, which is what's going on Russia, that is a recipe for a revolution. And Putin understood that.

Basically, Putin had been in power for too long, had stolen too much money and was desperately afraid that someday, some match – and he has no control over that match – is gonna light up. And that's what he's most afraid of. Putin needs this war to stay in power. If he doesn't have this war, he would lose power. And therefore, this war is gonna carry on for a lot longer than any of us could ever hope for. And it's only going to end if either Russia wins or Ukraine wins.

[The war is] only going to end if either Russia wins or Ukraine wins

ME: If you're saying that the equation is such that the war in Ukraine is critical for Putin's survival, then let's continue the discussion then with the position that President Trump plays.

BB: People ask me this a lot, 'why is Trump doing this?'. And I can say some reasons that people have speculated that are reasons I don't believe to be the case. It's pretty clear that Trump is on Putin's side. And I say that looking at the facts and ignoring the words. Trump has cut off military aid for Ukraine. We saw that absolute horrendous meeting in the White House with Zelensky, where then we saw American soldiers literally on their knees rolling out a red carpet to Putin's plane in Alaska.

So, and everybody asks me all the time, and I'm not some Trump whisperer, I don't know the answer [as to why], but I can state the obvious. It's not because there's some tape. Everyone says, ‘what do the Russians have on Trump?’. There's not a tape. But the tape, if there is a tape, is not gonna influence Trump. He's un-blackmailable and as he says, he could shoot somebody on Fifth Avenue and he can get away with it.

I put no stock in the compromised version of the story. The second thing that people are always throwing out there is that Trump has historic financial entanglements with Russia. They say that Russians funded his operations, real estate operations, when he was bankrupt, et cetera. And that may very well be true. I don't know the details. I mean, I know some of the details, but not all of them. But the other thing I can tell you, with 100 per cent certainty, is that if the Russians had lent him money, that would be absolutely no reason why he would behave himself.

I think it's pretty simple that Trump likes rich people. I think he thinks that Putin's a rich guy. I think that he thinks that Putin can do some business with him somehow. I don't know what that business is, but there's a lot of different avenues.

ME: Is there any opposition left in Russia? Is there internal dissent recognising Putin's control over the media, the judiciary, all of it? And do you see any hope for this match to be lit?

There's no organised opposition in Russia

BB: There's no organised opposition in Russia. Anybody who is a member of the opposition is either dead, in jail or in exile. There's no possibility of being an organised opposition leader and sitting in Russia. But that doesn't mean that people are happy with what's going on. And I don't think you can trust the opinion polls.

However, and this is really important, I'm sure all of you will remember Yevgeny Prigozhin, the head of the Wagner Group, marching towards Moscow. And he wasn't even anti-Putin; he was just anti the head of the army and anti the Defence Minister. They were fighting it out. And it blew up and they tried to kill him. They tried to kill Prigozhin and that's what precipitated his march. And his march was originally just towards Rostov, where the defence ministry was headquartered, or that's where their main base was. And then the momentum started building, and he marched towards Moscow.

But what was interesting on that day was two things. One, people were coming up to the tanks and putting flowers on the tanks and offering candy to the tank drivers and wanting to take selfies with them. And everyone was dead quiet. Nobody was saying anything publicly. But the other interesting thing is that there's an app called Flight Radar where you can track jets, and when Prigozhin was marching on Moscow, all sorts of planes were taking off out of Moscow and St Petersburg with all the oligarchs because they knew that if Prigozhin took over, he would want their money.

So, the Prigozhin thing, what it showed you was [that] they weren't loyal to Putin; they just wanted to know who's the big boss, who do we report to. And what that tells you is that he's sitting in a very uncertain place. They're not there for the love of Putin, they're there because they're scared of him. And at any point, if that fear were to diminish or stop, Putin would be gone.

This is an abridged version of the conversation with Bill Browder. The film of the conversation can be viewed in full here.