Turkey: Erdogan tightens grip on rule heightening concerns over authoritarianism

At the end of June, Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan won 52.6 per cent of the vote in snap presidential and parliamentary elections. The result further entrenches Erdogan’s rule after fifteen years as President. The contest was more challenging than in previous elections, but victory paves the way for the implementation of controversial constitutional reforms, replacing Turkey’s parliamentary system with an executive presidency.

The new constitution, passed in last year’s referendum, allows the President to directly appoint members of the High Council of Judges and Public Prosecutors (HSYK), issue legislative decrees, dismantle parliament, and remove civil servants without parliamentary approval, among other things. Critics continue to voice concerns about authoritarianism and the elimination of the government’s system of checks and balances.

‘The rule of law is already designed to serve Erdogan,’ says Zeynep Altiok, a member of parliament from the main opposition party, the Republican People’s Party (CHP). ‘He is the only one who can assign members to all justice boards meant to oversee equality and freedom.’

What is needed is systematic action to restore respect for human rights, allow civil society to flourish again and lift the suffocating climate of fear that has engulfed the country

Fotis Filippou

Deputy Europe Director, Amnesty International

Erdogan’s primary opposition in the election was Muharrem Ince, the CHP’s presidential candidate, who gained 30.6 per cent of the votes. ‘Ince’s voters believe in democracy and that deeply rooted democratic values could defeat the authoritarianism being developed. This is a major achievement and holds potential for Turkish society,’ says Ünal Çeviköz, Deputy Chairperson at the CHP. In a speech in Ankara, Ince vowed to oppose one-man rule in the legislature, judiciary and government and ‘keep up the fight as someone who got the approval of one person among every three in Turkey’.

Hans Corell, Co-Chair of the International Bar Association’s Human Rights Institute, believes that political parties and a periodic change in government are a sign of a strong democracy. ‘What is happening in Turkey at present is not only offering an opportunity for the opposition parties to come together,’ he says, ‘they must understand that it is a necessity.’

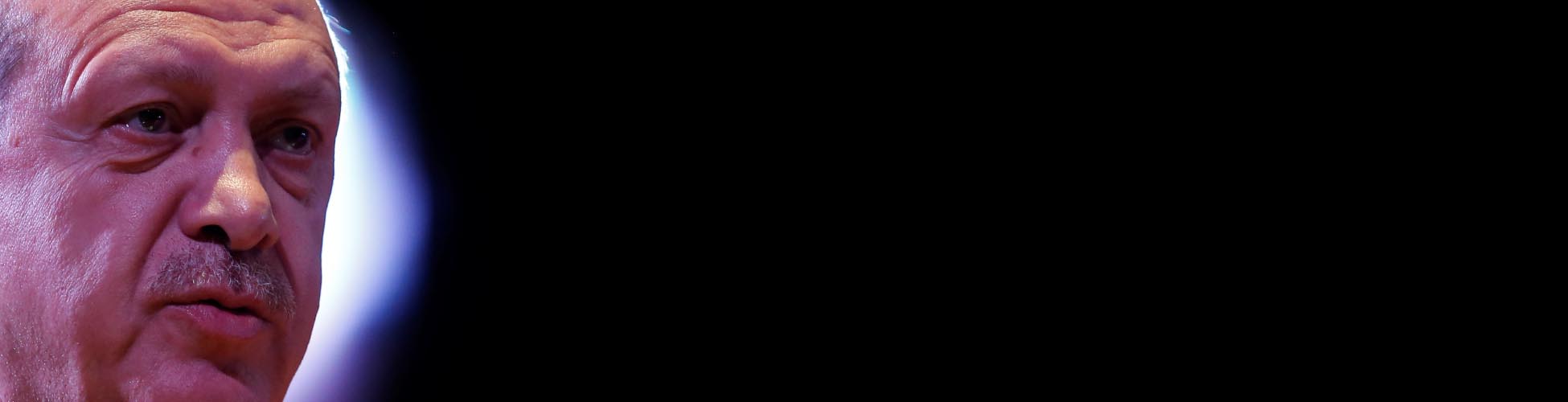

President Erdogan addresses his supporters during a rally in Izmir, Turkey, April 2017

Both Erdogan and Ince made ending the state of emergency – in place since 2016’s attempted coup – part of their campaign. The anti-terror package intended to replace the state of emergency is now under review by parliament. The proposed bill comes as a weary government keeps a close eye on the army and the opposition under its thumb. The government, for example, retains the power to purge members of the civil and security services, and governors will have the right to forbid people from gathering at certain places, set a curfew for public events, and ban protests that ‘would make the lives of residents unbearably difficult’. These new rules would be in effect for three years, a proposal that opposition parties consider more dangerous to individual freedoms than the state of emergency itself.

Since the attempted coup in 2016, more than 130,000 government employees have been dismissed from their jobs by presidential decree. About 6,000 academics have lost their jobs, and scores of journalists have been sent to jail. To address the lack of investigations and due process for public servants dismissed on terrorism charges, and following international pressure, the Turkish government established an ‘Emergency Law Commission’ in January 2017. Only 1,300 employees out of 108,905 applicants have since been reinstated. Following Erdogan’s election win, the government issued a decree to dismiss another 18,632 state employees over alleged links to terrorist groups.

Supporters of President Erdogan back his promise to boost the economy, strengthen security, fight terrorism and position Turkey on the world stage. But there are widespread concerns about the dangers of one-man rule. ‘Under the state of emergency it is very difficult to speak of free elections,’ says Sanar Yurdatapan, an advocate for freedom of expression and a spokesperson for the Initiative for Freedom of Expression - Turkey. Over 100,000 websites were reportedly blocked in 2017, including a high number of pro-Kurdish websites and satellite TV channels. The June election was also dotted with irregularities. The TV watchdog RTUK said Erdogan and his allies had 181 hours of air time from state-owned TRT channels, compared with just under 16 hours for Ince and his backers.

Human rights abuses are a major concern for activists and international watchdogs. On 20 March, the UN released a report condemning Turkey’s human rights violations in the post-coup climate. The report listed arbitrary deprivation of the right to work and of freedom of movement, torture and other ill-treatment, arbitrary detentions and infringements of the rights to freedom of association and expression.

‘The lifting of the state of emergency alone will not reverse this crackdown,’ said Fotis Filippou, Amnesty International’s Deputy Europe Director. ‘What is needed is systematic action to restore respect for human rights, allow civil society to flourish again and lift the suffocating climate of fear that has engulfed the country.’

‘Turkey is a member of the Council of Europe and subject to the jurisdiction of the European Court of Human Rights,’ adds Corell. ‘It is my sincere hope that Turkey in the future will organise itself in a manner that it meets the requirements of a democracy governed under the rule of law.’

'I believe democracy is a dream in Turkey now,' says Altiok. Yet despite President Erdogan’s win, about half of Turks who voted did not pick him. That’s a challenge for him to face even with new vested powers.