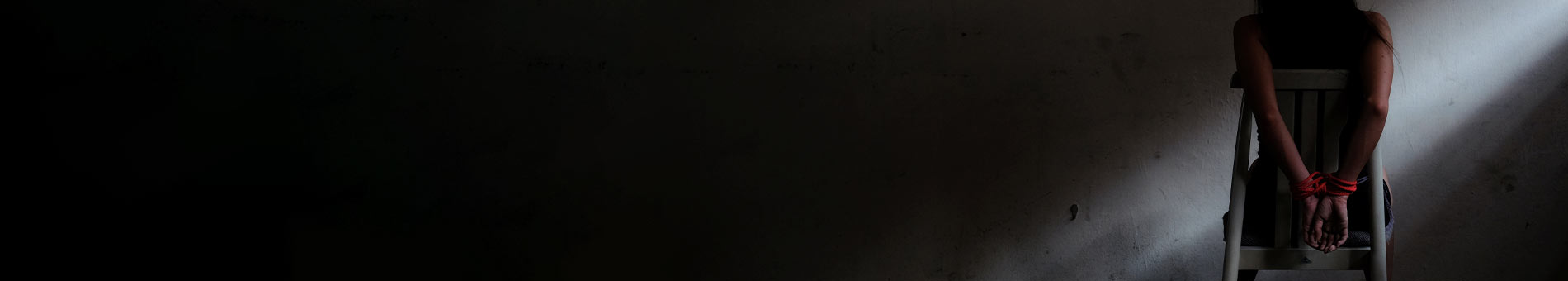

US anti-trafficking law continues to court controversy

In April 2018, American President Donald Trump signed into law a package of bills aimed at curbing the online exploitation of sex trafficking victims. It was hailed by legislators as a boon to prosecutors in their fight to police websites where sex is sold, as well as enabling trafficking victims to file lawsuits against these sites. The immediate impact was staggering, but there are growing concerns the law is pushing the problem of sex trafficking further underground.

The Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act and Allow States and Victims to Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act (SESTA-FOSTA) became law on 11 April 2018. It repealed Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996 under which websites were not liable for content posted by third parties, effectively making them immune from prosecution. Suddenly, classified advertising websites like Craigslist were forced to shut down their personal ads amid fears they could be seen as sex-related.

‘I think those of us who were working in this field didn’t really expect the law to have an immediate impact,’ says Valiant Richey, a former US prosecutor who is now acting coordinator of the Office for Combatting Trafficking in Human Beings at the Organization for Security and Co-Operation in Europe (OSCE).

Richey worked for 13 years as a senior prosecutor in Seattle. He says it was clear the problem of commercial sexual exploitation was vast in a country where buying sex in all but one state was ostensibly illegal. Using some of the technology tools that we used in our operations we were able to measure the impact of the law and that impact was stunning,’ Richey says. ‘Within 24 hours some of the biggest websites in the country that were hosting these ads shut down. The daily volume of ads went from about 100,000 a day to 20,000 a day within a week. 80% of the online marketplace was just eviscerated.’

The law has also come under considerable criticism. Some argue it conflates sex trafficking with consensual sex work and the repeal of Section 230 makes it more difficult for them to screen clients, leaving them vulnerable to exploitation. What’s more, the law’s bid to make sex trafficking easier to detect and prosecute has seemingly backfired as it’s closed down many of the online forums and sites that had previously made human trafficking more visible to law enforcement.

“In my experience, nobody has ever passed a law that eviscerated 80% of an illegal market within days

Valiant Richey The Office for Combatting Trafficking in Human Beings, OSCE

‘Websites provided a digital footprint, with key data and information that allowed law enforcement to investigate sex trafficking and find victims,’ says Luz Nagle, a Professor of Law at Stetson University College of Law, who co-chaired the IBA’s Task Force against Human Trafficking. ‘Many website administrators voluntarily reported probable sex trafficking cases to law enforcement. Federal prosecutors were able to go after Internet sites and individuals participating in sex trafficking.’

A case in point is Backpage.com. The website, notorious for carrying sex ads, was seized by the US authorities on 6 April, five days before SESTA-FOSTA had even made its way to the Senate for approval. The site’s founders and five other employees were held on charges, including facilitating the prostitution of teenage girls and money laundering. The website was permanently shut down. And all this happened without the need for SESTA-FOSTA.

Nagle says the law has forced sex trafficking ‘underground’ leaving victims ‘hidden and buried, and exposed to more danger.’ Now both prosecutors and companies will need more resources to identify victims. She says many websites will also be forced to rely on unreliable systems and algorithms to police their users’ activity, which could cause more trafficking victims to slip through the net. ‘Existing technology fails to distinguish between trafficking victims and consensual sex workers,’ says Nagle. ‘More concerning, automated filtering fails to detect trafficking victims seeking help or narrating their stories. Individuals will need to do additional content review, which requires trained staff to mitigate liability properly.’

Richey admits the law is not without criticism, but says it has helped reignite the debate about how to stop human trafficking. ‘Some new websites have come online and the number of ads has begun to creep back up again, but this was a policy outcome like we’d never seen before,’ he says. ‘In my experience, nobody has ever passed a law that eviscerated 80% of an illegal market within days. This opened up a whole new line of thinking for us around how we could end human trafficking.’

If SESTA-FOSTA does make sex trafficking harder to monitor, the task ahead looms large. According to a report by the US Justice Department, in 2017 US law enforcement agencies initiated 1,795 trafficking investigations, but convicted only 471 sex traffickers. These are disappointing numbers in a marketplace, where sadly the demand side for paying for sex remains all too high. Efforts to fight sex trafficking continue, however. Despite the government shutdown, on 11 January President Trump signed a new law authorising $430 million of federal funds towards combating human trafficking in the US and abroad.

Cyrus Vance Jr, District Attorney for New York County, agrees with Richey that SESTA-FOSTA will help the US get a grip on sex trafficking. However, he thinks a state-by-state approach may be key to resolving the problem for good. ‘What you really need to be successful in this work is you need the right laws in each state,’ he says. ‘Recently our laws in Manhattan have changed to enable us to better prosecute sex trafficking when minors are involved.’ Vance says the legislation has been hugely positive for his office and brought New York in line with 48 other states. ‘New York was just out of step…this is going to make our work easier in terms of prosecuting sex trafficking of young men and women.’