Asean: unlocking the potential of the single market

Margaret Taylor

Nearly four years after its creation, the Asean Economic Community is still struggling with integration. Could China’s investment in Belt and Road hold the key to its success?

At its inception in 2015, the Asean Economic Community (AEC) was full of promise and hope. Not only was the trading bloc expected to level the playing field between the ten states in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, it was supposed to transform the integrated whole into an Asian powerhouse. Nearly four years on – and with major international trade agreements crucial to its success failing to materialise – practically all of that promise has yet to be realised.

The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) were expected to be transformative for the AEC. The TPP was intended to link Asean countries Brunei, Malaysia, Singapore and Vietnam into a 12-strong trading partnership that, crucially, included the US. The RCEP will bring down trade barriers between all ten Asean countries, as well as Australia, China, India, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea.

Though not all of its members were signed up to each, manufacturing supply lines were being created whereby one Member State could send parts to another on a duty-free basis for finished goods to be assembled and sent to lucrative markets in Australia, Canada and the US free of charge. It was seen as a win-win situation.

Despite being signed in 2016, the TPP wasn’t ratified and, after assuming the US presidency in 2017, Donald Trump abandoned the plan altogether. President Trump cited the need to protect American workers from competition from low-wage economies, such as Malaysia and Vietnam. The move saw the US President rip up the trade deal and sever his country’s ties with East Asia. The remaining signatories are taking the agreement forward as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). But, for this group – including Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore and Vietnam – being unable to access one of the world’s largest consumer bases is a major setback.

Similarly, the RCEP was designed to strengthen the economic ties between Asean and the Asian nations it already has free-trade agreements with. It too has yet to come into force. This is despite negotiations beginning in 2013 with a view to the agreement being in place by 2018. As with the TPP, the RCEP was expected to have a significant impact on the AEC by giving its members even greater access to two of the largest markets in the world: China and India. Though the participating countries have signalled their intent to get the deal signed off this year, it is still not clear when the agreement will be concluded. ‘There is effectively now a race to complete the RCEP to fill the void left in globalisation by protectionist US policies,’ says Kasamesunt Teerasitsathaporn, a partner at Thai firm Tilleke & Gibbins.

‘Delays to the RCEP have been a hallmark of the negotiations since they began, but the pace actually seems to be picking up in light of the US–China trade war and the US withdrawal from the TPP,’ Teerasitsathaporn says. ‘Following [a members meeting in] Tokyo in 2018, and the withdrawal of the US from the TPP, momentum for greater integration across Asia has grown dramatically. Although little practical impact will be seen until the RCEP finally comes into force, a mandate to complete it in 2019/2020 exists, and if successful, will result in a major boost to economic supply lines in and out of Asean, China and the rest of the Eastern Pacific Rim.’ It remains a big ‘if’.

Finding unity

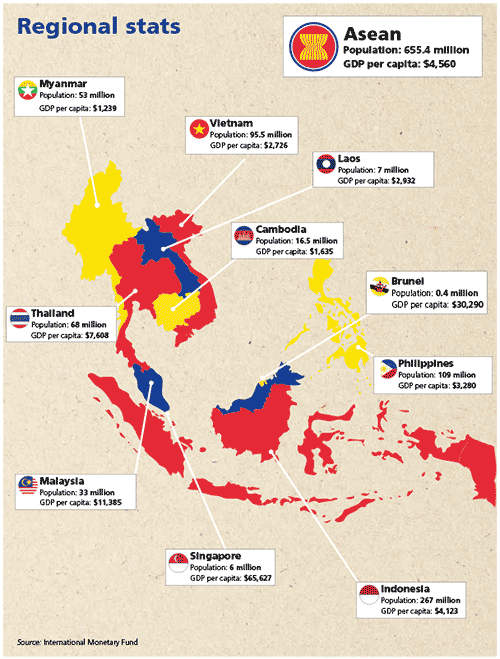

It would be easy to portray the TPP’s transformation into the CPTPP and the RCEP’s ongoing delays as the reason for the AEC’s slow start. In truth, the project’s problems are far more deep-seated. The idea of a single market was dogged with issues from the start, due to its Member States being so disparate. Underdeveloped Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar are, after all, streets apart economically from much larger neighbours Malaysia, Singapore and the tiny but oil-rich nation of Brunei.

Though the creation of the economic bloc was supposed to help close that gap, that it existed in the first place meant the region’s wealthiest nations were best placed to reap the benefits of the community when it went live, while those that had the most to gain from it were starting on the back foot. Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam, for example, had not lifted the tariffs necessary to make the region a true free-trade area on day one. This has made them less attractive as entry points for those looking to do business in the AEC.

Akil Hirani, Managing Partner of Indian firm Majmudar & Partners and Co-Chair of the IBA Asia Pacific Regional Forum, says not much has changed in the past three years, with little hope of the economic disparities being eliminated in the near future. That means the vision of the AEC as a fully integrated single market will remain unfilled. ‘There remains significant inequality among the members themselves,’ Hirani says. ‘Consequently, the least-developed countries, including Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar, have experienced fewer benefits as members of the AEC vis-à-vis developed countries, such as Singapore or Malaysia. Therefore, by and large, it has remained an integration of convenience rather than a consolidated trading bloc that propels the region’s development as a whole.’

Nor is it just their economies that divide the Member States. Ramesh Vaidyanathan, Managing Partner of Mumbai firm Advaya Legal and Treasurer of the IBA Asia Pacific Regional Forum, notes that the political and cultural differences between the Asean nations is hampering AEC integration too. That poses a challenge for anyone looking to invest in the region. ‘The group includes three constitutional monarchies, two communist states, three republics, a sultanate and a former military junta,’ he says. ‘Per-capita GDP ranges from more than $40,000 in Singapore and Brunei Darussalam to around $1,000 in the emerging economies of Cambodia and Myanmar. There is currency regulation in economies such as Malaysia and Vietnam and political worries in Thailand. I think each of the member countries continues to be seen very much as individual and therefore the challenge of attracting foreign investment plays out in Asean’s economies in different ways.’

By and large, it has remained an integration of convenience rather than a consolidated trading bloc that propels the region’s development as a whole

Akil Hirani

Managing Partner, Majmudar & Partners, India;

Co-Chair, IBA Asia Pacific Regional Forum

While those differences were among the main strengths of Asean when it was simply an intergovernmental organisation – its determination to reach agreement through consensus rather than decree – when it comes to presenting a united front to investors, that poses a problem. Indeed, Ross Becroft, Principal at Melbourne firm Gross & Becroft and Secretary of the IBA International Trade and Customs Law Committee, believes that having to find a consensus in everything – or failing to find a consensus in everything – could prove the biggest weakness in the development of the AEC.

‘The main issue is the fact that the AEC members are diverse culturally, geographically and economically, and with Asean there has been a need to accommodate such diversity in developing its objectives,’ he says. ‘What is most important is that the legal machinery developed within the AEC is sufficiently rigorous so that there is legal certainty [but] Asean has been around for a long time and it has always been a flexible and culturally diverse organisation so legal rigour may be a challenge.’

Source: International Monetary Fund

Though each Member State should be working for the good of the single market, the fact the principles of the AEC are not legally binding means there has so far been little imperative for them to do so. South Asia Law Founding Partner Gary Biesty, who previously spent nearly three decades with international firm Mayer Brown, notes that without the structures required to foster greater integration at a regional level, each Member State is continuing to prioritise its own interests over that of the collective.

‘Much was expected of the AEC in the years leading up to 2016. In particular, Thailand hoped it would reignite the country’s aspirations to become a regional hub for various sectors, notably IT and services,’ Biesty says. ‘In my view, this has not materialised and this is no doubt in part because other member countries harbour the same aspirations. One of my firm’s prime focuses is foreign direct investment into Myanmar and Thailand. I cannot identify any deal we have closed in the last three years that could be attributed to the AEC.’

The group includes three constitutional monarchies, two communist states, three republics, a sultanate and a former military junta. The challenge of attracting foreign investment plays out in Asean’s economies in different ways

Ramesh Vaidyanathan

Managing Partner, Advaya Legal, Mumbai;

Treasurer, IBA Asia Pacific Regional Forum

That’s creating a vicious cycle that works against the further development of the project as a whole, with competition between Member States often serving to heighten the differences that made integration tricky at the outset.

‘The differences have caused tensions and forced members to often look inwards rather than strive for comprehensive integration,’ Hirani says. ‘The Rohingya crisis in Myanmar, for example, did not sit well with the members with a Muslim majority, namely Indonesia and Malaysia.’

Despite this, it would be unreasonable to write the project off at this early stage of its development, with Teerasitsathaporn noting that, when they laid out their vision for the bloc in 2015, the AEC Member States said it would be a decade before they fully achieved their goal of becoming ‘highly integrated, cohesive, competitive, innovative and dynamic’.

‘The optimism of the early days of the community has been dampened a little by patchy harmonisation from country to country,’ Teerasitsathaporn says. ‘However, that’s inevitable in a trade bloc with such a wide disparity in levels of development between nations, and delays don’t mean that momentum has stalled – far from it in fact. Some incredible strides forward have been made in some of the least-developed countries in the bloc, perhaps most visibly in Myanmar’s adoption of modern, world-class company laws and intellectual property laws in 2018 and 2019. We are seeing similar enthusiasm in projects across all of the middle and lower income of the bloc, and although they may be a little slower than expected by the standards of countries in advanced stages of economic development, by the mean standards of the Member States, progress has actually been quite rapid.’

Market-making: the TPP/CPTPP and the RCEP

Signed in 2016, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) was an ambitious free-trade agreement that aimed to eliminate trade barriers in a bloc of 12 Pacific Rim countries that collectively account for 40 per cent of the global economy.

In addition to setting a high bar for standards relating to employment rights and environmental protection, the agreement promised to gradually reduce thousands of tariffs over time and would have also required its signatories to open up state procurement to foreign competition, rather than giving state-owned enterprises preferential treatment.

Brunei, Malaysia, Singapore and Vietnam were the four Asean countries that joined the founding group, which was also made up of Australia, Canada, Chile, Japan, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru and the US.

The agreement was strongly supported by America’s then President, Barack Obama, who promoted it as a means of maintaining America’s influence on the world stage in the face of an increasingly dominant China. It was never ratified by the US, though, and when Donald Trump won the 2016 presidential race, he pulled the country out of the agreement within his first few days in power. The reason, he said, was to protect American workers from overseas competition.

Despite the setback, the remaining 11 countries signed a new agreement in March 2018, with the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) maintaining around two-thirds of the provisions of the TPP. Some provisions the US had insisted on, such as those relating to oil and gas developments, did not make it into the CPTPP. So far, the agreement has been ratified by Australia, Canada, Japan, Mexico, New Zealand, Singapore and Vietnam, and speculation is mounting that the UK and even China may seek to become partners in due course.

Like the TPP and CPTPP, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) is a proposed free-trade agreement that promises to open up trade links for key nations in Southeast Asia, only this time the partners are based solely in Asia Pacific. As well as the ten Asean Member States (Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam), the agreement includes Australia, China, India, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea. Collectively, these countries account for around 28 per cent of global trade.

Though the agreement sets out specific rules for global trade, those rules are less onerous than those outlined in the TPP and, according to its detractors, would erode workers’ rights.

While it was due to come into force at the end of 2018, the RCEP has still not been fully ratified. It is expected that the agreement will be up and running sometime in 2019 or 2020, although no firm timeline has been given.

Martin Desautels, Managing Partner of Mekong law firm DFDL, agrees, noting that Asean businesses looking to tap into export markets have been particularly adept at responding to the opportunities the AEC presents. ‘On the business front, the creation of the AEC has dramatically changed how businesses see the Asean region and how businesses approach the region,’ he says. ‘Notably, it has steered businesses in developing a much more integrated Asean approach and, for manufacturing, we have seen the development of a more integrated Asean supply chain.’

In China’s hands

Though Chew Seng Kok, Chairman of Asean law firm network ZICO Law, says the economic differences between, for example, Myanmar and Singapore are such that ‘the idea of bringing them together in a single integrated union is miles away’, it appears clear that this may never happen unless the CPTPP and RCEP finally get off the ground. The difference now is that while the US was to be a significant driver of the AEC’s fortunes via the TPP, now it is China – the dominant force behind the RCEP – that is in charge.

While Chew notes that the RCEP ‘is China’s baby’, speculation is also rife that the superpower could become a signatory of the CPTPP. It is thought that the benefits to all parties could be huge, particularly if other Asean countries, such as Indonesia and Thailand, also signed up. Indeed, in a briefing paper issued by the Peterson Institute for International Economics earlier this year, Peter Petri of the Brandeis International Business School in Massachusetts and Michael Plummer of Johns Hopkins University in Maryland said the gains would be ‘driven by a sharp expansion in trade among CPTPP members estimated at around 50 per cent’.

For manufacturing, we have seen the development of a more integrated Asean supply chain

Martin Desautels

Managing Partner, DFDL, Mekong

‘Chinese membership in the CPTPP would yield large economic and political benefits to China and other members,’ they wrote.

‘The CPTPP, in its current form, would generate global income gains estimated at $147bn annually. But if China were to join, these gains would quadruple to $632bn, or a quarter more than in the original TPP with the US. They would be even greater if other Asia-Pacific economies joined as well. For example, a CPTPP-16 agreement with five more members – say, Indonesia, Korea, the Philippines, Taiwan and Thailand, all of which have expressed interest – would yield benefits of $449bn per year without China and $1,225bn with it.’

The problem is that, as the dominant force in Asia, China is more than adept at pushing its own agenda at the expense of its trading partners. This is most obvious in the way its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – which seeks to foster trading relationships across Africa, Asia, Europe and South America through the construction of physical infrastructure – has developed, with the project widely seen as being detrimental to the very countries that would stand to benefit most from having China as a trading partner. Indeed, while Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Vietnam have been huge beneficiaries of BRI capital flows, a number of projects have already been scaled back for fear they would leave the countries involved heavily indebted to China.

That some of the projects have been renegotiated recently shows just how ambitious China’s price tags have been, with Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad cancelling plans for a $14.3bn railway funded by state-owned China Communications Construction before later renegotiating the project for a third of the cost. Similarly, the price for a deep-water port that Chinese state-run business CITIC Group had planned to build in Myanmar fell from $7.3bn to $1.3bn when it looked like the Bay of Bengal project might be shelved.

Overcoming contradictions

Viewed like that, the AEC – or at least its individual Member States – may well want to exercise caution when it comes to further deepening relationships with China. As Becroft says: ‘There is certainly cautious reflection about China’s BRI project.

It is positive that China is prioritising capacity building in Asia and beyond, but it is obviously an example of China’s growing influence and countries value their independence and relations with other countries as well.’

For Hirani, the AEC’s ambiguity towards China has been heightened by the country’s actions in the South China Sea, with Asean nations such as Thailand siding with the Asian superpower in its various territorial disputes, while those that have the most to lose from those disputes, such as the Philippines and Vietnam, have distanced themselves from it. ‘The inequality within the members makes it difficult for them to take a unified stance in many scenarios,’ Hirani says. ‘For instance, despite the negative implications of China’s actions in the South China Sea on the AEC’s ability to guarantee economic benefits, the overlapping claims of several AEC members and national interests posed a significant hurdle to the AEC presenting a unified front.’

It’s a conundrum that will continue to be pondered in a region where progress is already being hampered by so many contradictory forces. Unless and until these contradictions can be overcome, the AEC’s dream of becoming the seventh-largest economy in the world will remain just that. As Chew at ZICO Law says: ‘The vision continues to be there but on the ground the AEC has not fulfilled its potential.’

Margaret Taylor is a freelance journalist and can be contacted at mags.taylor@icloud.com