Fatou Bensouda - interview transcript

Fatou Bensouda is the Chief Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court in The Hague. A Gambian prosecutor, she worked as a legal adviser at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda in Tanzania and has a wealth of experience in the international judicial system. In conversation with IBA journalist Ruth Green, she spoke about the Court’s jurisdiction and its fight against impunity, and quashed allegations of African bias.

Ruth Green: First of all, prior to your current role at the ICC you held a number of interesting positions, including working at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda. What was your role there like? And how do you think it prepared you for your role at the ICC?

Fatou Bensouda: I served in my native country of The Gambia up to the level of Minister of Justice and Attorney-General, before leaving to go to Rwanda. While I was in The Gambia, I prosecuted a lot of very serious cases, murders and rape and so on, but I have to say that nothing prepared me for the enormity of the crimes that I had to deal with in Rwanda.

It included a massive number of victims, a huge number of perpetrators, very serious atrocity crimes, war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide. So the magnitude of it cannot really be compared to the national system, but, at the same time, the experience that you come with from the national system in prosecuting crimes such as murder or rape does help you a lot when you get to the international scene.

RG: As you just noted, a lot of the victims that you would be seeing are some of the most vulnerable people in society, whether victims of sexual abuse or genocide. How effectively do you think the ICC can manage these sorts of crimes and ensure that the perpetrators are brought to justice?

FB: The main idea, the main motivation and the main impetus for the ICC to be established by the international community was to ensure that there is accountability for these serious atrocity crimes when they are committed. Of course, the primary responsibility to investigate and prosecute remains with the national jurisdiction – they have to do that.

But by establishing the ICC, the international community was saying that when these crimes do occur in a country, and the responsibility is not taken up to investigate and prosecute, the ICC, as an independent, impartial institution, should step in to investigate and prosecute. This is what the Court has been doing since we started work.

We are looking into these very serious crimes that occur, and where no justice is being done at the national level, then the ICC will intervene. But, as you know, the ICC can only intervene in the territory of a State Party. Also, when these serious crimes – ICC crimes, war crimes against humanity, genocide – when they are committed by a national of a State Party, then we have jurisdiction over those crimes.

The ICC is a court of last resort. It is not a court of first instance

And this is why the ICC jurisdiction is much wider than only the territories of the 123 States Parties of today. Because if nationals of those States Parties commit crimes on the territory of non-States Parties, then the ICC could potentially have jurisdiction over the national committing those crimes.

This is why I believe that the ICC is really a very important institution established in this century. It is here to make sure that we are able to judge people where we have jurisdiction and, where we are able to investigate and prosecute these crimes, to bring a measure of accountability and justice for the hundreds of thousands of victims.

RG: It’s interesting that you’re talking about jurisdiction. As you’ve mentioned, there is frequently a misunderstanding of exactly when the ICC can intervene. You’ve often been asked about ISIS atrocities and I think in the past you’ve said that the jurisdiction is currently ‘too narrow’ for the ICC to intervene. Do you think this is something that could change? Or is it something that requires something else, or perhaps somebody else, to intervene?

FB: When I explained that, currently, the jurisdiction is very limited, it is because Syria is not a State Party. Also, Iraq is not a State Party. And, as a result, we do not have territorial jurisdiction to start with. I have just mentioned about having personal jurisdiction over nationals of States Parties who commit these atrocity crimes. We’ve got information to say that among the foreign fighters, among the ranks of ISIS, there are nationals of States Parties [to the ICC].

Therefore, ISIS’ jurisdiction – its personal jurisdiction – over those nationals of States Parties is possible. We are requesting information and we are asking to be provided with information by, especially, the countries where those nationals come from and from any other reliable source to see what the ICC is able to do regarding that personal jurisdiction. We do, of course, have to follow our policies and our practices in the sense that we would normally go after those who are most responsible for the crimes.

From the information we have today, it is not the nationals of States Parties who are occupying the highest responsible positions in the hierarchy of the ISIS structure. So, therefore, there is a bit of a problem in going after them because they are not the most responsible.

However, we are receiving information and we are hearing that there may be nationals of States Parties occupying very responsible positions. But these are things that we have to look at very carefully, we have to see, we have to assess, we have to look at all the information that we can get, and then a decision will be made.

Also, I need to explain, again, the issue of complementarity. Complementarity is a principle of the Rome Statute system by which if the government whose nationals are among the ranks of ISIS are [already] investigating and prosecuting, the ICC will not. The ICC is a court of last resort. It is not a court of first instance.

This means that when governments are genuinely investigating and prosecuting these crimes, then the ICC will take a back seat. And, of course, it will observe what is happening and how those prosecutions are taking place. It is not meant to shield anyone. It is meant to genuinely investigate and prosecute.

If there is no accountability, there will not be justice for these crimes and there will not be justice for the victims of these crimes – this would be unacceptable for me

RG: There has been some criticism in relation to the ICC’s investigation into the Ivory Coast, and I think there have been some allegations of bias. What would you say in reaction to that? Have there been any changes that have been introduced – or changes in your colleagues’ thinking perhaps – about how to investigate these sorts of incidents?

FB: I think the accusation that we have been biased is totally wrong, to start with, totally wrong. If you recall, Côte d’Ivoire made a declaration accepting the jurisdiction of the ICC before actually ratifying their own statute and becoming part of the ICC.

You know the challenges of investigating and prosecuting these crimes. It takes time. It does not happen overnight. We have also announced publicly, and even together with the authorities in Côte d’Ivoire, that we will open a second investigation into Côte d’Ivoire. We have said that from the very beginning.

And even they themselves recognise the need for the Court to do that and they are not against it. When we are investigating, or when we start investigating, we do not make it a very public event. If we are working, we are working confidentially for obvious purposes, so as to protect witnesses and our staff. We work quietly.

And maybe that is what is responsible for these criticisms and accusations that the ICC is only working on one side and not the other. I say this just to emphasise that this is what the office has decided – we are going to investigate both sides to the conflict.

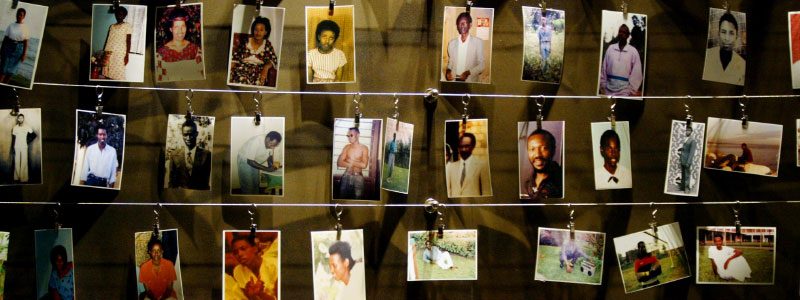

An installation of pictures of victims, donated by survivors, on a wall inside the Gisozi memorial in Kigali, which depicts the country’s 1994 genocide in which 800,000 Tutsi and politically moderate Hutus died.

REUTERS/Radu Sigheti

In short, what I want to say is that it is the evidence that guides us. It is not all this other criteria. When we open investigations, it means that our criteria have been met, that the crimes have taken place and it is grave enough to warrant the intervention of the ICC. It is not against the interests of justice to intervene in these situations, where no national proceedings are ongoing with respect to those crimes. This is what we look for before we determine whether to open investigations or not.

RG: As you say, these investigations involve a huge amount of resources, a lot of people, and a lot of decision-making needs to be done. And I would imagine, therefore, it must be quite costly. I know that you rely on funding from the States Parties to the Rome Statute. Do you have any concerns that future investigations will be able to happen in the way that the ICC would see fit? And that you have the capacity to undertake all these investigations at any given time?

FB: What has been happening over time is that there are a lot of demands on the office. Obviously, there are now many more cases before the ICC than when we started. What is happening is that the resources that we are provided with to do our work, and to do it effectively and efficiently, are not matching the workload of the office.

And, in the past, I have had to prioritise those cases that we feel are rather urgent and by urgent I mean that we are engaging in the judicial process at that moment, or very soon. So we prioritise those cases over others, we delay starting a case, or we even suspend starting investigation until the next year, because we do not have sufficient resources needed to be able to conduct our investigations effectively and efficiently.

RG: There have been examples of Member States that have not followed injunctions. Does this affect the credibility, or are there any concerns that the actions of these members have affected the credibility, of the ICC’s work?

FB: The ICC, the Court itself, created under the Rome Statute, is a system. A system of international justice in which the ICC will do its judicial work, and the decisions that the judges take will be executed by the Member States. This is the system. If one is working and the other not, the system would not work.

If the ICC is doing what it was set up to do, that is, delivering justice, and it’s not assisted and supported by the Member States who set it up, then this system that we have put in place to fight impunity, to bring accountability and justice, will not work.

And this is what is happening, there are some Member States – not all – that are not cooperating with the Court as they should. And I do not think that the credibility of the ICC is at stake when this happens. It’s really that the members are not taking that responsibility seriously, that legal obligation, actually.

RG:You mentioned there are certain limitations to the jurisdictional basis of the ICC intervening in a particular case. And sometimes this relates to certain countries, but a lot of people have questioned whether there’s a bias towards Africa, and I think you’ve had to answer questions about this in the past. What would you say to that? And do you think it’s still the case that there is no African bias?

There has never been any African bias. There is no African bias, and there will never be an African bias

FB: Indeed, there has never been any African bias. There is no African bias, and there will never be an African bias. I keep saying that those who are making the accusations should really try and look at the realities on the ground, as it gives you a completely opposite scenario. It gives you the scenario that it is actually African governments, African countries and African Member States that are coming to the ICC to request intervention. This is really what is happening.

And I can lay out all the countries that have requested the ICC’s intervention: Uganda did; the Democratic Republic of Congo did; the Central African Republic on two occasions requested the ICC to intervene. First, over the events that took place in 2003 when we charged Jean-Pierre Bemba with atrocity crimes, and the second case was in 2014.

Mali has also requested the ICC to step in and exercise jurisdiction. I believe I mentioned Côte d’Ivoire also, which first requested the ICC to intervene by making a declaration under Article 12.3 asking for ICC jurisdiction, as they were not a Member State. But they followed it immediately afterwards by ratifying their statute and becoming a Member State.

So, you can say that all of these countries have requested ICC intervention. Then we have Libya, and we have Sudan. In Sudan and Libya, it was the UN Security Council, acting under Chapter VII, that decided to refer the situation to the ICC. Under the Rome Statute, the UN Security Council can do that, but I just want to make clear that the ICC will not automatically investigate situations referred to the ICC by the UN Security Council.

Of course, we have to take the steps that we do to assess every situation, ensure that these are crimes that are under the ICC’s jurisdiction and make all the checks that we do when there is a normal referral. We do it before we take the case. In both Libya and Sudan, we have done this before stepping in to investigate and prosecute these crimes.

Having explained to you about all these referrals that have come to the ICC, and how the ICC is asked to exercise jurisdiction by these countries, I also want to add the important role the African states have played in setting up the ICC. If you go through the records of the negotiations for the ICC, you will realise that if it had not been for that big push by African states to have the ICC established, perhaps we would not have it today. Maybe later, but we would not have had it as soon as we did.

Another thing that I want to mention is that nobody can deny that these crimes are taking place in the situations that have been referred to the Court. And there are victims of those serious atrocity crimes. And those victims are African victims. I do not think that it is justified to say that the ICC should not intervene because they are African victims and they do not deserve justice. I think they do.

And finally, I also want to mention that this criticism and accusation that all our situations are in Africa is also untrue. This is not the case. We are conducting preliminary examinations outside of Africa: in Afghanistan, in Colombia, in Honduras, in Palestine, in Ukraine and in Georgia. We are conducting preliminary examinations in all of these situations. And if, in any of them, my jurisdiction is met, I will not hesitate to open investigations without fear or favour.

RG: Being from Africa yourself, from The Gambia, you have really become a role model for women in Africa, in terms of the legal sector generally, as well as in the judiciary and the international judicial system. Do you think, throughout your career to date, that things have changed a lot for women in Africa wanting to work within these related spheres?

FB: Something I know is that, throughout Africa, women play a very important role and they are there as partners side by side with our male counterparts, always willing to step up to the plate and work. My role as ICC prosecutor, I hope, is encouraging younger women, other women, to realise that there is no glass ceiling.

Whether it’s real or imagined, there is no glass ceiling, and we have the potential to fully grow into what we can be. I sincerely believe that the people of the next generation, or the younger generation who are coming up, will have this in mind. What is important, always I think, is to work very hard and stay focused. There is really no limit, and no one should make us believe us that there is a glass ceiling, whether it is real or it’s imagined.

RG: You’ve received a lot of accolades and prizes in your career. Are there any awards or any moments in your career that you’re particularly proud of, in terms of the contribution that you’ve made?

FB: The work that I’m doing now, of course. I’m doing it after having also served my national government. But what is always important for me is the plight of victims. The fact that in some way with my work, I am able to contribute to giving them a voice, I’m able to help them to at least experience that justice can be done and will be done.

When I see that they’re having a voice, they are participating in the proceedings, they are telling the world what has happened to them and how they have been victimised, these are moments that always give me pride. They always give me pride, but they also humble me.

It humbles me in the sense that I am able to at least contribute somehow to their plight. For me, this is what keeps me going. This is my motivation all the time. If there is no accountability, there will not be justice for these crimes, and there will not be justice for the victims of these crimes – this would be unacceptable for me.