Denmark adopts new foreign direct investment legislation

Nikolaj Juhl Hansen

Magnusson, Copenhagen

njh@magnussonlaw.com

Denmark has become the latest European Union country to introduce rules controlling certain foreign direct investments (FDI). Denmark, traditionally a very open economy, introduces – in the words of the Danish Government – a ‘robust’ FDI regime in the ‘more restrictive’ end of what has yet been seen across the EU. Critical voices have characterised the rules as ‘trawling where fly-fishing is required’. The new rules apply to any transaction closing after 1 September 2021.

The legislation is based on the EU regulatory framework from 2019 requiring EU Member States to review their national FDI screening rules. The framework also mandates the establishment of a line of communication where FDI transactions of relevance to the national security and/or public order of one or more Member States may be discussed.

Foreign direct investment comprises a significant part of the Danish economy. During the period 2013–18, Denmark received foreign investment at an amount of approximately €518bn. This is equivalent to 30.9 per cent of the Danish GDP, of which approximately circa 75 per cent came from other EU/European Economic Community countries.

Denmark has opted for a very broad definition of foreigners in its implementation of FDI regulations. It includes not only persons and companies from other EU countries, but also Danish companies where a foreigner maintains ‘control’. The control test is somewhat similar to the test applicable to defining ultimate beneficial owners of businesses in Denmark. Defined control under the FDI regime begins with control of more than 25 per cent of the shares or votes in a Danish enterprise, or an ability for the foreigner to exercise control otherwise – for instance, through veto rights or the right to appoint directors or officers.

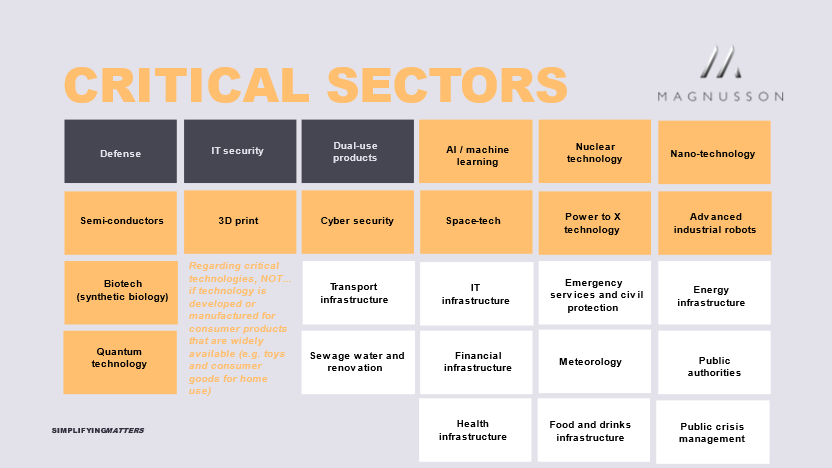

Additionally, Denmark has defined a wide range of critical sectors, technologies and infrastructure where FDI transactions will need approval to be able to complete. The areas cover traditional defence and military sectors, but also extends well beyond these sections (see Table 1).

Table 1: Critical sectors

The FDI rules apply where:

- a foreigner acquires ownership or control over 10 per cent, 20 per cent, one-third, 50 per cent, two-thirds or 100 per cent of shares or votes; or

- acquires ‘similar’ control (including in jointly owned enterprises) such as a right to appoint members of the management organs as well as having the ability to make or veto certain decisions.

At the outset, there are no de minimis thresholds in the Danish FDI legislation, neither monetary nor otherwise. This means that transactions of any value, as well as a transaction concerning a Danish enterprise where only 1 per cent of its business is deemed ‘critical’, will be caught by the FDI regime. In terms of critical infrastructure, any Danish enterprise ‘supporting’ critical infrastructure, including companies that are suppliers of components or services to critical infrastructure, may be deemed a critical infrastructure company and consequently subjected to the FDI regime.

The transactions relevant for the Danish FDI regime include:

- traditional M&A and investment transactions;

- long-term finance and lease agreements and certain asset deals;

- acquisition of shares listed on a stock exchange;

- setting up a subsidiary in Denmark; and

- a Danish company entering into a ‘special economic agreement’, including certain R&D joint ventures, outsourcing, and supply agreements.

Having listened to critical voices from the Danish startup environment, Denmark will allow a foreign investor to invest up to DKK 75m (€10m) in a startup during the first three years of its lifespan, as long as the startup company you invest in does not come under the foreign investor’s control or become a subsidiary of the foreign investor.

For international M&A practitioners, it is of particular importance to note that the Danish rules also cover an indirect change of control over a Danish business. Consequently, the Danish FDI regime has extra-territorial effect, causing any cross-border M&A transaction where a foreign owned/controlled parent or group which owns a Danish subsidiary (subjected to the FDI restrictions) to be subject to mandatory governmental approval in Denmark.

As is the case across the EU, FDI transactions may only be blocked if they present a threat to Danish national security or public order interests. However, the FDI regimes are different to one of the other major regulatory hurdles – merger control – in that each country is given the discretion to define what constitutes national security or public order.

For that reason, the EU will continue to see FDI regimes mushrooming up in different shapes and forms across the Member States, creating for a complex regulatory environment, especially in cross-border M&A deals where the target has operations in numerous countries.

The Danish rules also contain a ‘gun-jumping’ prohibition. Any transaction that is subject to Danish FDI approval must halt and await clearance from the Danish Business Authority before completing. If you run the red light and proceed without approval, the Danish authorities can exercise a range of powers, including seizing control over the shares of the Danish entity.

The duty to seek clearance in Denmark lies with the foreign investor. Normally, the Danish Business Authority will – after having received ‘full information’ – have 60 days to review the application. The transaction is not automatically approved if the deadline is not met.

In addition to the mandatory filing regime, Denmark has also introduced a voluntary notification regime as well as a possibility for pre-screening of potential transactions.

Europe has recently seen some significant FDI-related cases, including the Norwegian government blocking a Swiss-based Russian buyer’s proposed acquisition of Rolls-Royce’s marine diesel engine manufacturer (Bergen Engines AS) and Canadian Couche Tard’s retraction of interest in French retail giant Carrefour after the French government stated that the supermarket chain was critical food supply infrastructure in France.

The Danish government has stated that the new rules are not intended to impact adversely on foreign direct investment into Denmark. If that statement holds true, and only a few FDI transactions are blocked, the adverse impact will in that sense likely come from the FDI process adding to the transaction timetable and in general adding much more complexity to a transaction process. This is particularly relevant for Danish mid- and small-cap M&A deals that have generally so far been able to proceed to closing without regulatory hurdles. Due to the gun-jumping prohibition, the buyer cannot assume control or otherwise exercise significant influence over the target pending the approval, which may drive buyers to an increased use of ‘material adverse change’ clauses trying to eliminate the risk of bad things happening to the target while the FDI screening is taking place.

In the bigger picture, the complexity of the international FDI landscape may impact adversely on deal certainty, pushing sellers towards buyers that are less likely to cause problems in relation to FDI screening. This may, of course, also impact negatively on valuations.