Our overcrowded prisons

Margaret TaylorFriday 12 January 2024

Prisons around the world are experiencing severe overcrowding. Global Insight asks whether it’s time for a fresh approach to criminal justice.

When Jalal was arrested on suspicion of theft in 2019, he spent 35 days in a Lahore prison cell with six other people. They couldn’t all lie down at the same time because there wasn’t enough space and, in the heat of the summer, he felt as if he was being ‘baked alive’. He ‘lost six kilograms in one month, permanently lost my hair and had bags under [my] eyes making me almost unrecognisable by the time I was released […] the experience has scarred me for life’.

A year later Shafiq had a similar experience, with the room he was held in ‘so clogged at night that it was almost impossible to get up and go to the bathroom without stepping on people’s heads and the only option was to wait till morning’. In 2022, when Irfanullah spent three weeks in prison after being accused of stealing a motorbike, he developed a skin allergy from the cramped conditions and reported that he and the others in his cell were so closely packed there was ‘barely any room for air to pass’ between them as they slept.

Their experiences are detailed in ‘A Nightmare for Everyone’: The Health Crisis in Pakistan’s Prisons, a March 2023 report from international non-governmental organisation (NGO) Human Rights Watch. The publication documents how the majority of Pakistan’s 91 jails and prisons were operating at more than 100 per cent capacity, with the ‘severe overcrowding’ compounding existing health issues while leaving inmates ‘vulnerable to communicable diseases and unable to access medicine and treatment for even basic health needs’. The overcrowding was, Human Rights Watch found, ‘intersecting with a range of other rights violations’ such as ‘inadequate and poor-quality food, unsanitary living conditions, and lack of access to medicines and treatment’. Pakistan’s government didn’t respond to a request for comment from Global Insight.

‘Seriously dangerous overcrowding’

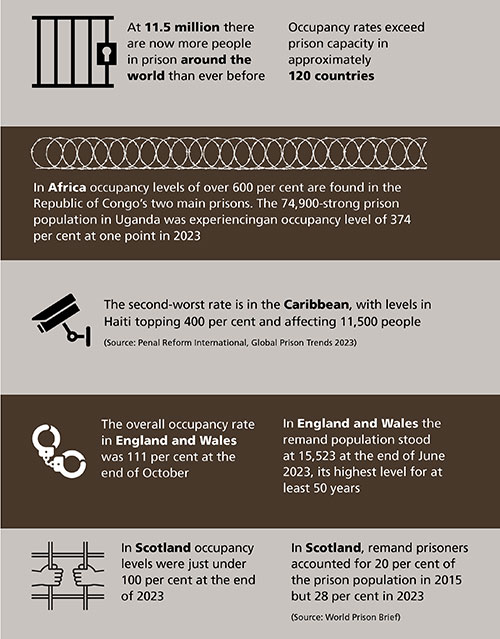

It’s not a situation that’s confined to the developing world. According to NGO Penal Reform International’s report Global Prison Trends 2023, at 11.5 million there are now more people in prison around the world than ever before and occupancy rates exceed prison capacity in approximately 120 countries. The worst overcrowding is found in Africa, the report states, with occupancy levels of over 600 per cent in the Republic of Congo’s two main prisons. The second-worst rate is in the Caribbean, with levels in Haiti topping 400 per cent and affecting 11,500 people, while the 74,900-strong prison population in Uganda was experiencing an occupancy level of 374 per cent at the time the report was published.

Data from World Prison Brief, which collates information on prison systems globally, shows that UK institutions are suffering from overcrowding too, with the overall occupancy rate in England and Wales sitting at 111 per cent at the end of October. In Scotland, where occupancy levels were just under 100 per cent at the end of 2023, a damning report issued by Auditor General Stephen Boyle, published in December, stated that occupancy was expected to tip over to 103 per cent by March 2024. The rate in Glasgow’s HMP Barlinnie is already considerably worse, with almost 1,400 prisoners packed into a creaking Victorian jail built to house just 987.

It's a situation that Sara Carnegie, Director of the IBA’s Legal Policy and Research Unit and the former Director of Strategic Policy with the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) of England and Wales, says has been building for some time. ‘I remember going into a senior policy adviser’s office when I was at the CPS and there was a huge chart on the wall showing prisoner numbers’, she recalls. ‘It was getting to the point of seriously dangerous overcrowding about five or six years ago.’

Part of the reason for the increase in England and Wales is the enhanced sentencing powers handed to magistrates, coupled with a hardening of the ‘tough on crime’ rhetoric coming from the government. This has led to overcrowding, Carnegie says, because the government’s agenda doesn’t include appropriately financing the system, ‘whether that’s courts, the police, the prison system’.

At the same time, prisons have been affected by the Covid-19 pandemic, with the backlog in cases that piled up when the courts were forced to close leading to a surge in the number of people being held on remand. In Scotland, remand prisoners accounted for 20 per cent of the prison population in 2015 but 28 per cent in 2023, while in England and Wales the remand population stood at 15,523 at the end of June – its highest level for at least 50 years.

A spokesperson for the UK’s Ministry of Justice admits that overcrowding in England and Wales is in part due to the government taking a harder stance on prosecution and sentencing. The spokesperson says, however, that the construction of six new prisons will help mitigate the issue. ‘We’re embarking on the biggest prison-expansion programme since the Victorian era, creating an additional 20,000 modern places to rehabilitate offenders and cut crime’, the spokesperson says. ‘We’re also letting our Crown courts run at full throttle by lifting the cap on the number of days they can sit for a third year, recruiting more judges and investing more in our courts. This includes Magistrates’ courts where more than 90 per cent of criminal cases are heard.’

However, Felicity Gerry KC, former Asia Pacific Regional Forum Liaison Officer on the IBA Criminal Law Committee and a barrister at Libertas Chambers in London and Crockett Chambers in Melbourne, Australia – where the country-wide occupancy rate is around 112 per cent – says that the overall impact of overcrowding in the meantime is that prison resources are stretched too far, making an already bad situation worse. ‘I’ve been in prisons in Australia, the UK and Indonesia, including death row, and all have been overcrowded’, says Gerry KC. ‘The biggest problem for England and Wales at the moment is the large number of young people, particularly young men between the ages of 18 and 25, who have nothing to do – they are locked up sometimes up to 22 or 23 hours a day.’

Putting people in prison with nothing to do is not only cruel and tortuous – whatever they have done as a crime – but a total waste of money

Felicity Gerry KC

Former Asia Pacific Regional Forum Liaison Officer, IBA Criminal Law Committee

Gerry KC explains that a large proportion of male prisoners’ conduct is violent, whether physical or sexual. ‘Clearly there’s a problem that needs to be addressed with male behaviour, but prisons are not designed to solve that problem’, she says. ‘We’ve created a system that’s much more likely to cause violence than to cure it. Putting people in prison with nothing to do is not only cruel and tortuous – whatever they have done as a crime – but a total waste of money. It wastes lives, particularly if those people could be rehabilitated. There are lots of people in there who are no risk if they could be helped.’

The second punishment

Notably, in recent months judges in other jurisdictions have refused to send inmates to UK jails over fears that their human rights would be breached due to the overcrowding. In July 2023, Irish High Court judge Justice Paul McDermott refused to extradite 24-year-old Richard Sharples to Scotland on the basis he would face a ‘real and substantial risk of inhumane or degrading treatment’ due to a lack of resources to address his mental health conditions. In September, the Karlsruhe Higher Regional Court in southwest Germany refused to send an Albanian national accused of drug trafficking to the UK after his lawyer successfully argued that chronic overcrowding, staff shortages and violence among inmates would breach the minimum standards required under the European Convention on Human Rights.

Emmanuel Moyne, former In-House Counsel Liaison Officer of the IBA Criminal Law Committee and a name partner at French law firm Bougartchev Moyne Associés in Paris, says the situation described by Gerry KC is replicated in France, where the overall prison occupancy rate was 122 per cent at the end of October, but reached more than 200 per cent in Perpignan and Nîmes in summer 2023 — an all-time high. Figures released by the French Ministry of Justice at the end of July showed that, in total, there were 16,643 more prisoners than there were places available in French prisons, with almost 2,500 inmates forced to sleep on mattresses on the floor due to the overcrowding. The Ministry didn’t respond to Global Insight’s request for comment on what action, if any, has been taken to remedy the overcrowding. As things stand, the situation is, says Moyne, a double punishment for everyone involved.

When you are sentenced to jail that’s the first punishment, but if you are sentenced to spend time in a jail where the living conditions are [poor] it’s a second punishment

Emmanuel Moyne

Former In-House Counsel Liaison Officer, IBA Criminal Law Committee

Moyne highlights that France is regularly sanctioned by the European Court of Human Rights about the situation its prisons are in, with the Court finding in 2020, for example, that prison conditions and the treatment of prisoners were in violation of the European Convention on Human Rights. ‘When you are sentenced to jail that’s the first punishment, but if you are sentenced to spend time in a jail where the living conditions are [poor] it’s a second punishment’, he says. ‘It’s a well-documented situation – the government, NGOs, lawyers and magistrates are aware of it – but it’s difficult to solve. You have to build new prisons, allocate money and funding. It’s crazy because the criminal justice system is one of the basics of democracy and justice and we should do everything which is possible to make it work.’

For Gerry KC, the fact that so many people are incarcerated in prisons that don’t have the capacity to house them appropriately, let alone rehabilitate them, shows that most criminal justice systems aren’t working properly. Rather than adding to prison populations by continuing to lock people up, governments should be looking at ways of reducing the number of inmates they already have.

‘We need to audit prisons to understand who is in there’, she says. ‘What about people with autism? They often have challenging behaviour, but we are labelling that as criminal behaviour. We should only be locking up those people who are a genuine risk to society. There’s research in Australia that shows that a very large proportion of the male prison population has a traumatic brain injury. Once they know that, they understand the condition and can address violent conduct. It might be men who have ended up in prison because of fighting and if they understand what has caused the behaviour they might be less likely to fight.’

Trialling alternatives

More than 30 of Africa’s 54 nations have overcrowded prisons, with Uganda (367 per cent in September 2023), the Democratic Republic of Congo (323 per cent) and Ivory Coast (319 per cent) joining the Republic of Congo as the countries with the highest levels of occupancy on the continent. In Nigeria, where the number of inmates on remand outweighs the number convicted and the overall occupancy rate was just over 160 per cent at the end of November, states are beginning to take matters into their own hands, with the Lagos State Government pardoning 30 inmates in July to help ease prison conditions. Reportedly, the Chief Judge of Lagos State, Justice Kazeem Alogba, released the group specifically to deal with overcrowding.

‘The inmates released are those who committed minor offences such as assault, disorderliness, low-level shoplifting, road traffic offences, theft and burglary, among others’, says Rotimi Oladokun of the Lagos Command of the Nigerian Correctional Service in an interview. ‘There is, however, a need to free more inmates as the state custodial facilities are housing over 8,000 inmates, which is above their capacities.’

Banke Olagbegi-Oloba, former Member of the IBA African Regional Forum Advisory Board and a law lecturer at Adekunle Ajasin University in Nigeria’s Ondo State, says poverty is a major driver of certain crimes in Nigeria. Rather than offering inmates a means of escaping poverty, however, she says prison only serves to make a bad situation worse, with the conditions inside the country’s institutions having an impact on prisoners’ mental health, which in turn affects their ability to earn when they’re released. Restorative justice, she says, offers a potential solution, particularly when the courts remain overstretched and remand populations are so high.

‘Poverty is not a good reason to steal or to commit crime but I can say for a fact that someone who is hungry and has been hungry for days might be more amenable to committing crime when there are no other options available’, she says. ‘Quite a number of people who commit minor offences are not educated; quite a number of them do not have skills that they can put to use to acquire an income that would meet their daily needs.’ She adds that, notwithstanding that a person might have committed a crime, they continue to have human rights – which the poor condition of prison facilities in Nigeria deprives them of.

If you want to get to the root of the problem, the solution has to be holistic and well thought out

Banke Olagbegi-Oloba

Former Member, IBA African Regional Forum Advisory Board

‘If you want to get to the root of the problem, the solution has to be holistic and well thought out,’, says Olagbegi-Oloba. Given that the government lacks the money to alleviate overcrowding, she says that one option is the possibility of bringing in mediation or alternative dispute resolution for simple offences, rather than holding offenders for a long time while they await trial.

Gerry KC agrees that alternatives to custody need to be found, especially for those being held on remand and particularly as the Covid-inspired court backlogs mean the time being spent on remand continues to increase. ‘There’s no reason with tagging why you can’t have electronic remand’, she says. ‘There’s no reason why you can’t have bespoke conditions for individual prisoners. That would reignite the principle of being innocent until proven guilty.’

However, a prison system that balances the upholding of prisoners’ basic rights while serving as a form of punishment to inmates isn’t necessarily an easy sell to the public – especially given the level of funding this would require to achieve, says Moyne. He argues that the public-at-large must understand that if someone requires treatment for mental health issues, they must receive that assistance and shouldn’t be put in jail without it, ‘because if you do that you’ll only worsen the situation’. But, he adds, ‘at a time when life is difficult, we had the pandemic, we have the war [in Ukraine]’, it can be difficult to justify spending money on the justice system.

Margaret Taylor is a freelance journalist and can be contacted at mags.taylor@icloud.com