Poverty: UN Rapporteur calls on governments to pursue ‘triple dividend measures’

In May, a UN expert group meeting in Geneva examined the progress made on UN Sustainable Development Goal 1, which calls for ending extreme poverty by 2030. The outcomes from the discussion will contribute towards the 2024 UN High Level Political Forum to be held New York in July.

While eradicating poverty is vital, the data suggests that, globally, we are behind schedule in freeing humanity from its deprivations by 2030. According to a UN Development Programme (UNDP) report published in 2023, 1.1 billion out of the planet’s 6.1 billion people – across 110 countries – are poor.

And while ending poverty and advancing human rights are closely linked goals within numerous international treaties and agreements, it can be argued that the fact that extreme poverty still exists in nations capable of eradicating it represents a direct infringement of fundamental human rights. ‘There’s an interesting tension between guiding principles on extreme poverty and human rights,’ says Bruce Ian Macallum, Co-Chair of the IBA Poverty and Social Development Committee and a practitioner in international public law based in Victoria, Canada. ‘Sometimes it is stated that people living in extreme poverty shouldn’t be denied human rights, but the discourse on the issue does not go far enough to state that by bolstering human rights, you can eliminate the very condition.’

‘My take on it is that you must do more than just recognise the human rights of people living in extreme poverty. You must change or ameliorate the underlying conditions so that extreme poverty does not exist,’ Macallum says. He adds that ‘there is an obligation under international law to do so in any event.’

Related links

You must do more than just recognise the human rights of people living in extreme poverty. You must change or ameliorate the underlying conditions so that extreme poverty does not exist

Bruce Ian Macallum

Co-Chair, IBA Poverty and Social Development Committee

In the UNDP report, multidimensional metrics complement those based on monetary poverty by assessing non-monetary deprivations, since an approach that monitors only a lack of income wouldn’t adequately address the complexity of extreme poverty – for instance, its impact on education, availability of safe drinking water, sanitation, healthcare and access to justice. In 42 out of the 61 countries with available data, there are a greater number of people suffering multidimensional poverty than extreme monetary poverty, with the latter defined by the World Bank as living on $2.15 or less per day.

However, understanding the multidimensionality of poverty is not the only key to overcoming it. According to the UN Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights, Olivier De Schutter, the approach to doing so based on economic growth has passed the peak of its usefulness.

In his book The Poverty of Growth, De Schutter explains why it’s necessary to expand our toolbox in the fight against poverty in order to be substantially less dependent on economic growth. Following a post-growth approach, policies to eradicate poverty would significantly differ from those adopted in the last decades by governments willing to do whatever it takes – including dismantling the rights of workers – to create what they term ‘a business-friendly environment’.

‘The major problem,’ says De Schutter, ‘is that the economic machine is essentially geared towards meeting the demand expressed by those who have enough purchasing power to send signals to the markets that certain types of goods and services have to be produced. In a market economy, mostly the resources are used to meet demand, not the social needs of people in poverty, but demand expressed by the purchasing power of the richest groups in society.’ Increasing overall output, he says, isn’t the most efficient way to meet social needs, but rather results in ‘inefficient use of the scarce resources at our disposal.’

The key, says De Schutter, is to be much more lucid about what we need to produce. ‘We should invest much more in public goods, education, healthcare, housing and public transport, and we should produce fewer mansions and private jets and powerful cars that will only be affordable to the richest in society’, he believes. He adds that moving to a post-growth approach will be a major challenge.

De Schutter speaks of ‘triple dividend measures’, which are policies able to achieve three objectives at the same time: reducing our environmental footprint, creating jobs that are accessible to people with low levels of qualification and providing goods and services at an affordable price for households on modest incomes. Triple dividend measures can be implemented in different areas, such as mobility, energy, agriculture and construction. 'For instance, insulating buildings is a way to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions from poorly insulated buildings, to create jobs in the construction industry and, finally, to reduce the bills of low-income households who live in poorly insulated dwellings’, he explains.

To take a second example, by investing in public transportation, societies can reduce the air pollution that results from individual cars and create jobs to service public transport vehicles such as trains and the infrastructure behind them. Thirdly, they can ensure that the right to mobility is also guaranteed for households who can’t afford an individual car. ‘So, we can absolutely achieve ecological transformation as a tool to reduce poverty and inequalities,’ says de Schutter.

In 2020, presenting his first report as Special Rapporteur, De Schutter addressed the UN Assembly on rebuilding the economy after the Covid-19 pandemic. In the document, he identified the synergies that can be activated to pursue policies that make the three objectives work together. 'We can combine the move to a low-carbon society with a concern for social justice. These are not incompatible objectives’, he said.

In September 2024, negotiations will begin on the next generation of development goals at the Summit for the Future in New York, as part of the 79th session of the UN General Assembly. An alliance of non-governmental organisations and unions, among other groups, will propose a post-growth scenario that they hope to see included in the new goals. ‘We will propose that governments study how to move towards improved wellbeing and meeting the social needs of the economy at the same time,’ says De Schutter. ‘In rich countries and advanced economies, economic growth cannot be the answer anymore. We are doubling the size of the economy every 30 years, [but] people are not happier, wellbeing is not improving anymore, and we need to focus on other priorities than just GDP [gross domestic product] increase.’

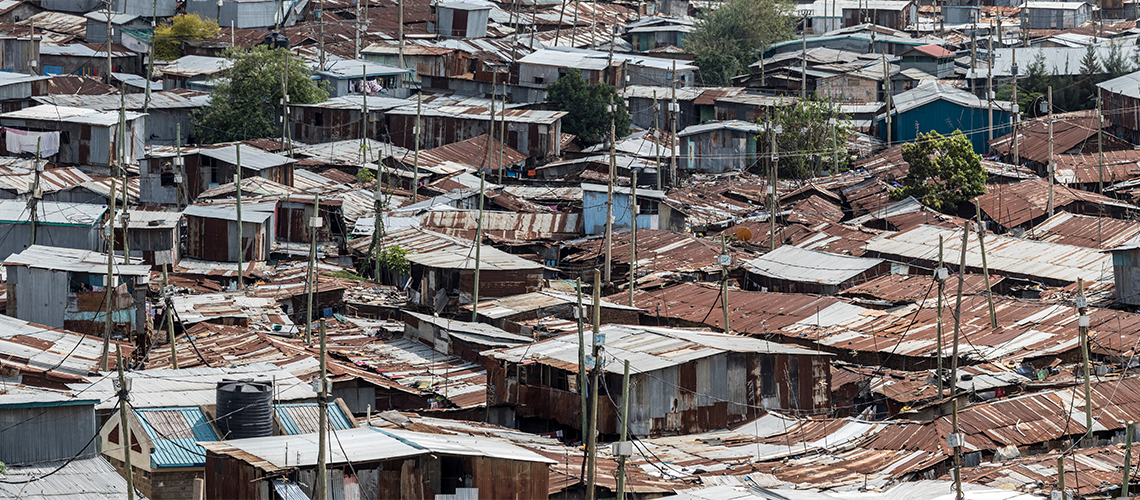

Image caption: High angle panoramic view of the Kibera slum in Nairobi, Kenya. By Wollwerth Imagery/AdobeStock.com