Relevant tax issues regarding M&A operations

Monday 19 May 2025

Pedro Afonso Avvad

FreitasLeite Advogados, Rio de Janeiro

pedro@freitasleite.com.br

The Brazilian tax system is complex and, in numerous situations, presents inconsistencies – not only among its rules, but also between the legislators’ intentions and the interpretation given by the relevant oversight bodies when applying such rules. In M&A transactions, the application of tax rules becomes even more cumbersome as the economic impact increases and as more parties and jurisdictions become involved.

The greater the economic impact of a transaction, the more significant the associated tax burden, which, if not correctly measured, may even render the deal unviable. Moreover, transactions that are economically significant tend to be subject to regulatory and antitrust constraints, which condition their completion and limit the available options to achieve the desired outcome.

The parties involved can also cause the same transaction to have different tax effects, according to their country of residence or a particular situation (individual taxpayer versus legal entity, regulated entity versus unregulated entity), making it necessary to seek structuring solutions that relieve one party without imposing an excessive burden on another.

In this article, we address some relevant issues that should be taken into consideration when structuring and implementing M&A transactions, in order to facilitate an adequate tax assessment and to prevent unpleasant surprises.

Although every tax is relevant in a business combination, it is undeniable that the most significant tax impacts occur in the area of income tax[1] and, regarding legal entities, corporate income tax.

Preventive approach and understanding the transaction

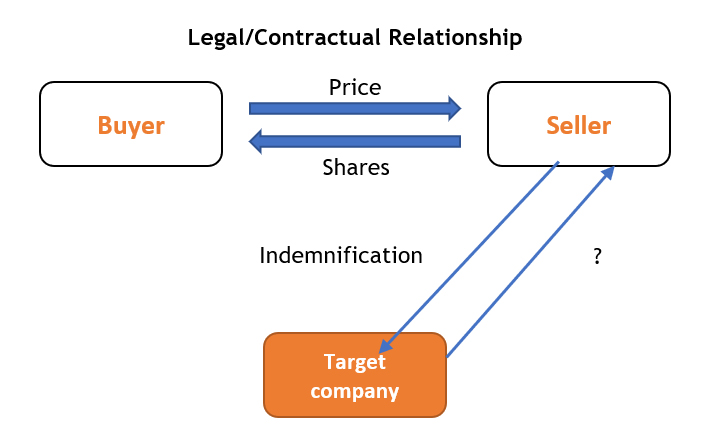

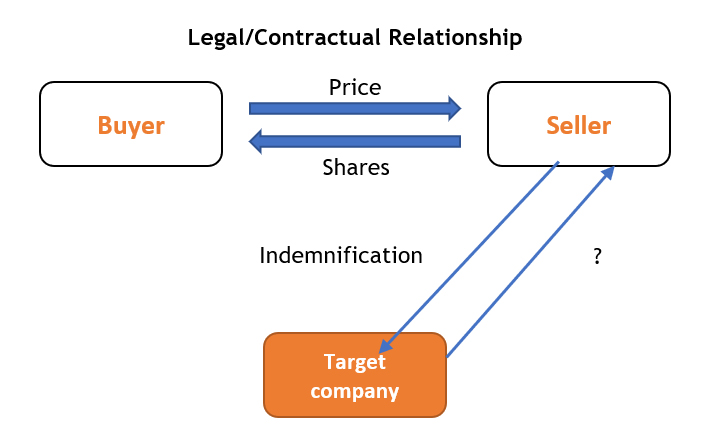

In an M&A transaction, it is advisable to evaluate the potential tax impacts from the outset – not only for the parties directly involved in the transaction (buyer and seller) but also for the target company and even for persons or entities that may be indirectly affected.

Although it is not uncommon for the parties to initially focus on issues such as valuation, price determination and the due diligence process, tax planning should be regarded as an essential part of the early conception and negotiation of the transaction. In other words, it should be analysed as early as possible – even before the preliminary documents are discussed. While this may increase costs during a phase when the outcome of the transaction is still uncertain, a preventive approach will undoubtedly lead to greater savings and lower risks for the parties involved.

Conversely, when this preliminary analysis is neglected until later stages of the transaction – for example, during the drafting of the definitive documents – the tax advisers are often left merely to present the applicable tax burden and to point out the risks of exploring alternative paths, which in many cases turn out to be excessive, particularly when inconsistencies arise between the preliminary documents (such as confidentiality agreements, memoranda of understanding or term sheets) and the final characteristics of the transaction. Today, such inconsistencies are a primary focus of scrutiny by tax authorities and may lead to allegations of tax evasion or the absence of genuine business purpose by the tax authorities.

Bearing in mind that, for legal entities, income tax (IR) and a social contribution tax, CSLL, are levied at a combined rate of 34 per cent (which may reach 40 per cent in the case of financial institutions), the absence of a preliminary tax impact analysis on the intended transaction can consume more than one third of its economic outcome. Moreover, considering the penalties imposed by tax authorities, a hastily structured transaction can not only generate an excessive tax burden but also result in fines ranging from 75 per cent to 150 per cent of the tax amounts.

Given this asymmetric risk, a preventive approach is recommended as the best way to achieve consistent tax structuring from the very beginning of the transaction.

It is clear at these early stages that the evaluation of tax aspects involves many uncertainties and variables, given the multitude of paths and alternatives for structuring the transaction. To reduce these variables, it is essential to understand the needs and interests of the parties involved – thereby immediately ruling out many alternatives and ultimately narrowing the analysis to a few feasible and tax-efficient structures.

As a starting point, the following issues should be assessed:

- the position of the parties: buyer (buy side), seller (sell side) or, in more complex transactions, whether the deal involves financing, restructuring, or a joint venture;

- the interests and motivations behind the transaction (which may include, for instance, business growth, an outright exit from the business, vertical integration of certain activities, product diversification, synergy capture and cost reduction, competitive defence, or even resolving financial or governance issues);

- the relevant assets held by the parties and the significance of those assets in the transaction;

- the financial and accounting positions of the parties involved, as well as of the target company and its key identified assets;

- the relevant tax risks and contingencies that have already been incurred and need to be addressed from the outset; and

- the strategic commercial plan of the parties post-acquisition, that is, whether the tax structure should encompass not only the transaction itself but also a restructuring, a subsequent asset sale, or even a future exit from the business, as is common in private equity investments.

A detailed understanding of these themes makes it possible to forecast the tax impacts resulting from the transaction and, when necessary, incorporate these impacts into the economic equation of the involved parties – ensuring that the entire transaction is developed consistently with the established structure, starting from the preliminary documents.

For instance, imagine a transaction between two companies that begins as a sale of key assets but eventually is negotiated as a spin-off of those assets, which are then transferred to a new company and ultimately sold by individual shareholders with a considerably lower tax burden. It is not uncommon for the preliminary documents to reflect the initially intended operation (asset sale between two companies) rather than what is ultimately executed (share sale by individuals in a company holding those assets). Although such a change is legitimate, modifying the structure after the initial deal has been agreed upon may be seen as a tax evasion mechanism if the sole purpose of altering the transaction structure was to reduce the tax burden. In such cases, the argument that the tax burden rendered a simple asset sale unviable will not persuade the tax authority.

To illustrate that this scenario is relatively common, consider the case involving the sale of a well-known furniture company that was subject to tax assessments by the Receita Federale do Brasil (RFB) on the grounds that the final transaction did not materially reflect what had been initially agreed upon. In that deal, multiple sellers were involved and each underwent reorganisations so that the stakes being sold were transferred from legal entities to individuals. However, it appears that each seller negotiated different contractual arrangements with the buyer: while some sellers entered into sale agreements with a suspensive condition (only implemented after the reorganisation), at least one seller executed a contract without any suspensive condition and, worse, received part of the price before the reorganisation. This discrepancy – stemming from a mismatch between what was initially contemplated and what was eventually formalised – led the Administrative Tax Council (CARF) to cancel the assessments for the first group of sellers (considering that the sale was only completed once the stake was held by individuals) while maintaining the assessments for the second group (on the basis that, at the time of the sale, the individuals did not yet hold the stake).

It is evident that while tax issues should not be the sole focus of an M&A transaction, they must remain a priority to ensure that an excessive tax burden does not undermine the strategic motives driving the deal.

Once the characteristics of the involved parties and their respective interests are understood, the analysis of the relevant tax aspects becomes more objective, thereby clarifying the possible paths to achieve the intended result.

Preliminary structuring and planning

As in many jurisdictions worldwide, Brazilian tax legislation provides for a series of special treatments that must be considered in advance of an M&A transaction, given their direct impact on the efficiency and profitability of such deals. These treatments range from the differences in tax burden between individuals and legal entities (which means that the tax incidence differs depending on who is selling a particular stake), to the existence of specific exemptions that can be utilised, and even to the tax effects on the amounts paid.

In this section, we address the key elements that have the most significant influence on the structuring of an M&A transaction and that, consequently, should be taken into account during the planning phase.

Under Law No 12.973/2014, when acquiring a stake – whether by purchasing existing shares or through a new issuance – a company must revalue the acquired assets and liabilities at fair value (per IFRS standard n 13). This process establishes whether there is a future profitability premium (goodwill) or a gain from a bargain purchase, each with distinct tax treatments.

The acquisition cost is allocated among the book value, any surplus or deficit, and the resulting goodwill. Tax benefits linked to goodwill (such as its gradual exclusion from taxable income) depend on meeting specific conditions such as transaction independence and proper documentation. Conversely, a gain from a bargain purchase – the excess of the investee’s net assets’ fair value over the acquisition cost – is treated differently, with its recognition deferred until the investment is sold or gradually included in the tax calculation in cases of mergers or demergers.

Additionally, in scenarios involving deferred payments or contingent considerations (earn-outs), these amounts must be recognised at fair value at the time of acquisition, affecting both goodwill and bargain purchase computations.

Considerations in negotiating the definitive agreements

Once the transaction is structured and the phase of drafting definitive contracts begins, attention to tax issues must focus on the impacts of certain contractual clauses, whose tax effects should be considered and properly addressed by the parties to avoid hidden liabilities.

In this context, there are several contractual clauses commonly found in M&A transactions that have significant tax consequences.

Indemnification for losses

One prominent example is the traditional indemnification clause, which sets forth various types of compensatory adjustments, each with distinct legal natures and, accordingly, different tax consequences. For instance, events that may trigger indemnification include:

- breach of contract;

- inaccuracy or violation of representations and warranties; and

- events that occurred prior to closing (eg, ‘my watch, your watch’ situations).

In effect, while a loss resulting from a breach of contract is naturally considered a compensable damage under civil law, those arising from inaccurate or misleading representations, or pre-closing events, are usually not compensatory for damages but rather are contractual obligations to perform. This distinction leads to entirely different tax effects, as indemnification for actual damages is not subject to income tax, whereas indemnification as a contractual obligation to perform typically has economic effects similar to a price adjustment.

Another debate concerning indemnification clauses relates to determining which party should receive the indemnity. It is not uncommon for contracts to include provisions for compensation directly to the target company. However, this situation is not supported by accounting principles, since the legal relationship is between the buyer and the seller; therefore, the contract should provide for different treatments in cases that demonstrate actual damage to the target company. Generally, the party suffering the loss should be indemnified, whether the obligation is to perform an action or otherwise.

An additional important point is the neutralisation of the tax effects of the loss, since such losses can significantly reduce the overall tax burden. In cases where the loss claimed corresponds to the materialisation of a contingency or a cost/expense incurred, these payments typically allow the target company to take a tax deduction for IR and CSLL purposes, and may even generate credits with respect to non-cumulative taxes (eg, federal excise tax (IPI), tax on commerce and services (ICMS), Program of Social Integration (PIS)/ Contribution for the Financing of Social Security COFINS, etc.). Therefore, it is advisable that the indemnification clause specifies that the indemnity amount shall be offset by the tax deduction effects of the loss.

Contingent assets

In contrast to indemnification for pre-closing losses – which are usually the seller’s responsibility – it is important to verify the existence of contingent assets, characterised by tax credits arising from overpayments or undue payments of taxes or any other claims made by the target company that would be deemed a contingent asset under the ‘my watch, your watch’ provision.

If contingent assets exist, their outcome can be subject to negotiation and may even serve to mitigate the effects of the indemnification for losses.

Escrow account

Regardless of the rules for the release of funds, an escrow account can typically follow one of two criteria: (1) it characterises a ‘withheld payment’ if it is in the name of the buyer, who maintains control over the funds; or (2) it functions as an ‘indemnity guarantee’ when it is held in the name of the seller, thereby falling outside the buyer’s legal sphere. In the first case, the buyer is subject to tax on any income generated by the funds in the escrow account; in the second, they are not.

Because the income earned on financial investments from the escrow account – and the funds deposited therein – are primarily intended for the seller, holding the escrow account in the buyer’s name may create a misalignment between the amounts withheld at source and the ultimate recipient of the funds.

It is worth noting that, in Brazil, the tax authorities have taken the view that the funds deposited in an escrow account only become available to the seller when they are actually released, making ownership in the seller’s name less risky from a tax management perspective.

After the closing

Finally, the tax effects of the so-called post-closing phase – when the business combination is implemented – should also be assessed, preferably in a preventive manner. Indeed, the integration phase may have tax impacts that are both significant and require careful management.

Before implementing any integration of product lines, personnel or services, it is advisable for the parties involved to analyse the implications of these activities, particularly in the following areas:

- supply chain integration: combining the operational logistics of two companies may make sense from a cost perspective, but the tax implications – especially concerning VAT – can make such consolidation complex;

- sale of non-core assets: in many M&A transactions, after the deal, the buyer may seek to dispose of duplicate or non-core assets. The tax aspects of such sales must be evaluated and taken into account;

- cross-border transactions: in transactions involving assets or operations in different countries, integrating procedures and structures becomes even more complex due to the involvement of multiple jurisdictions, which can only be mitigated by treaties to avoid double taxation;

- tax management systems: another relevant issue relates to management systems. Currently, companies are required to adopt digital tax bookkeeping in place of traditional tax record books. If the companies use different systems, a preliminary analysis is important to identify potential issues arising from a lack of integration – especially given the high penalties for submitting incorrect information; and

- cost sharing: since many M&A transactions aim to capture synergies and reduce duplicate costs, the parties should consider entering into cost-sharing agreements and decide on the best structure for establishing a centralising entity.

Final considerations

Given the dynamic nature of tax rules, it must be acknowledged that the issues presented herein represent only some of the relevant tax aspects commonly encountered in M&A transactions.

It would not be an exaggeration to state that this article may be completely outdated with respect to the substantive law in just a few years; therefore, it is fundamental to verify the current applicability of the rules on each issue at the time of structuring or negotiating an M&A transaction.

[1] From now on, corporate income tax and individual income tax will be addressed as income tax, as a general expression.