The end of aid as we know it

Isabelle Walker, IBA Junior Content EditorThursday 22 May 2025

Rohingya children eat from jars with the USAID logo on them, at a refugee camp in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh, 11 February 2025. REUTERS/Ro Yassin Abdumonab.

Significant cuts to US foreign aid will have far-reaching repercussions. Global Insight assesses the consequences and the future of the aid sector.

The decision of President Donald Trump’s administration to suspend funding to the US Agency for International Development (USAID) was met with global condemnation. Undeterred, the administration has moved to dismantle the agency, cutting 83 per cent of USAID’s programmes and reducing its staff to only 15 positions.

The consequences are set to be devastating. In 2024 the US was the world’s biggest donor of overseas development aid – contributing almost $62bn, significantly more than the second largest contributor, Germany, which spent $31.4bn. The programmes supported by USAID were diverse, from funding community kitchens in war-torn Sudan to assisting Ukraine in restoring its food exports to pre-war levels, and aiding counter-narcotics efforts in Colombia.

This fundamentally outward-looking mandate appears to have made USAID a target of Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency, tasked with drastically cutting US government spending.

Jean-Paul Faguet, Professor of the Political Economy of Development at the London School of Economics, says the justifications for cutting aid ‘feed into the MAGA [Make America Great Again] discourse about how foreigners are ripping off Americans.’ Perhaps hinting at this sentiment, Tammy Bruce, Spokesperson for the US State Department, has said that ‘President Trump has stated clearly that the United States is no longer going to blindly dole out money with no return for the American people.’

Fatema Sumar, Executive Director of the Harvard Center for International Development, identifies a number of ongoing longer-term trends as also leading to the USAID decision, including rising inflation and fiscal tightening following the Covid-19 pandemic. But, Sumar says, even if what’s happening in the US is the most ‘politically dramatic’ activity in the sector, the country isn’t alone in moving in this direction on aid.

In February, the UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer announced a reduction in the country’s foreign aid budget from 0.5 to 0.3 per cent of gross national income (GNI). The government justified the decision by saying the £6bn gained from the cuts would allow defence spending to be increased in this ‘dangerous new era’, alluding to Russia’s warmongering in Ukraine and the suggestion that the US will no longer step in to support Europe militarily.

In Belgium, the government recently announced that it would cut its foreign aid budget by 25 per cent over a five-year period. Germany, the largest aid donor in the EU, is also forecast to slash funding for overseas aid. The next government’s coalition contract omits the 0.7 per cent GNI commitment to foreign aid – a target set by the EU and the UN respectively – for the first time in 30 years. Meanwhile the Netherlands has announced plans to reduce spending on international development by €2.4bn, beginning in 2027, as it prioritises the ‘interests of the Netherlands’, which the government says include trade, migration and security.

Although the cuts in European countries are dwarfed by the impact of the USAID freeze, they indicate that the scaling back of foreign aid is an international trend, as opposed to rogue US policy. The reduction of foreign aid commitments in a number of European countries seen over the last few years is due primarily to budget pressures, Faguet says. ‘Governments are worried about providing improved living standards for their citizens, and to do that they need to make more public investments,’ he explains.

International damage

Whatever the specific domestic causes of the reduction in aid, the cuts have raised significant concerns about those who rely on aid programmes, as well as the safety of those employed in the industry and the future of the sector.

Since the USAID freeze in January, operations to provide water and electricity to Yazidi communities in Sinjar have been halted, while over 1,100 communal kitchens have been shuttered in Sudan. HIV-positive patients in South Africa face a shortage of medication. ‘The funding freeze has brought dire consequences to vulnerable populations,’ says M Ravi, an officer of the IBA Human Rights Law Committee.

In particular, he draws attention to the impact of the move on key international health programmes, such as the clinics in Kenya providing care for tuberculosis and HIV. Many of these clinics received funding from PEPFAR (the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief), which has been a bastion of US overseas aid and a symbol of its commitment to global health for over two decades. The initiative – the largest health programme established for a single disease – funds antiretroviral therapy, HIV testing and counselling services, and is estimated to have saved over 25 million lives. In Kenya, PEPFAR supplied around 40 per cent of the country’s HIV medications and supplies.

A study, published in The Lancet medical journal, estimates that cuts to PEPFAR could cause an additional 4.43 to 10.75 million new HIV infections and 0.77 to 2.93 million HIV-related deaths between 2025 and 2030 compared with the status quo.

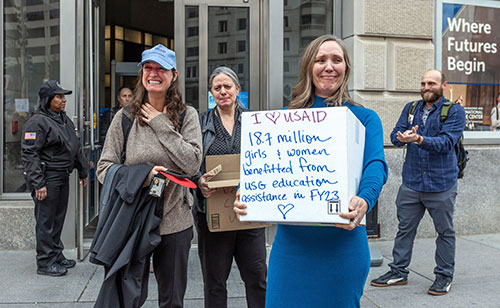

USAID employees and their supporters outside a Washington, D.C. federal building after being fired. 27 February 2025. Leigh Green / Alamy Stock Photo.

Meanwhile in Afghanistan, the Women’s Scholarship Endowment (WSE), a USAID-funded programme, covers the tuition fees and living expenses for 120 Afghan women to study STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) courses overseas, primarily in Oman and Qatar. The Endowment also runs online classes for students unable to leave Afghanistan. The opportunity provided by WSE is significant for Afghan women, who have been banned from secondary and higher education in their own country by the ruling Taliban.

In March, reports emerged that 80 students in receipt of the scholarship and studying in Oman would face an imminent return to Afghanistan after their funding was terminated. One student, speaking anonymously for fear of reprisals, said the group in Oman had been informed that they would be sent back to Afghanistan within two weeks. The US State Department later confirmed that the funding would continue until 30 June 2025. It’s unclear what’ll happen after that date.

The uncertainty has led to distress among the students. ‘If we are sent back, we will face severe consequences. It would mean losing all our dreams,’ one student said. ‘We won’t be able to study and our families might force us to get married. Many of us could also be at personal risk due to our past affiliations and activism.’

While other countries, economic blocs, multilateral organisations and philanthropic groups can partially fill the aid gap, the consensus is that they’ll not be able to completely plug the vacuum left by the USAID freeze.

One country looking to step up its engagement in foreign aid and replace USAID’s presence, at least some areas, is China, which Faguet describes as ‘rushing at speed into the big gap the West is leaving.’

China’s haste is indicative of the benefits to be reaped. The goodwill and reputational benefits generated from China’s funding of key infrastructural projects set the nation up as a key trading partner to other countries, while factories constructed overseas might be used to process goods for Chinese markets. Beyond this, China is ‘trying to become the hegemon, they’re trying to be the big superpower that is a rival system that displaces the US,’ Faguet says, ‘and they’re succeeding in doing that, because the US is just ceding the terrain.’

Further, the position of the US on the international stage is being affected. The country has traditionally been seen as a leader in global humanitarian efforts, but cuts to aid – particularly in areas such as health, disaster relief and development – ‘may signal a shift away from its commitment to addressing global challenges, leading to perceptions of diminished moral authority,’ says M Ravi, who’s an international human rights lawyer at M Ravi Law, based in Bangkok.

Cuts to aid may signal a shift away from [the US’] commitment to addressing global challenges, leading to perceptions of diminished moral authority

M Ravi

Officer, IBA Human Rights Law Committee

Sumar says one of the biggest casualties to emerge from this self-induced crisis will be the loss of trust between the US and its partners around the world. A former US diplomat, Sumar says she has seen first-hand how relationships between countries can be damaged in an instant. ‘Just as in a friendship where it takes many, many years to build [trust] and it only takes moments to break – I think that’s true at a country level as well,’ she says.

Who helps the helpers?

Cuts to aid don’t only reduce humanitarian assistance – they also endanger the safety of those delivering it. Aid agencies depend on funding for protective infrastructure, security personnel and specialised training, says Yusra Suedi, an assistant professor in international law at the University of Manchester. ‘With fewer resources, they become more exposed to threats in conflict zones and may struggle to negotiate humanitarian access with local authorities or armed groups,’ she says.

In recent years, attacks on aid workers have become increasingly common, with the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) recently confirming that 2024 was the deadliest year on record for humanitarian personnel. According to data from the Aid Worker Security Database (AWSD), 344 aid workers were killed in 2024. This surpasses the 2023 total of 280 deaths. ‘The rise in attacks on humanitarian workers is not just a security concern – it’s a legal crisis,’ says Suedi.

Non-compliance with international humanitarian law (IHL) and a disregard for the authority of institutions such as the International Criminal Court (ICC) are among the factors that have led to an increase in attacks on aid workers and a lack of accountability for those who conduct them. Markus Beham, Co-Vice Chair of the IBA Human Rights Law Committee, says that impunity for IHL violations and a disregard for the interventions of the ICC may lead to a ‘kind of institutional degradation.’

In this context, providing the proper infrastructure, planning and support to keep humanitarian workers safe and respond to their needs is crucial. But the cuts are a threat to these mechanisms.

The International NGO Safety Organisation (INSO) provides a standardised platform to both national and international non-governmental organisations (NGOs) for the purposes of information sharing, allowing for better access to crucial intelligence and therefore enabling those on the ground to address and mitigate against future risk.

China is rushing at speed into the big gap the West is leaving

Jean-Paul Faguet

Professor of the Political Economy of Development, London School of Economics

In a sector frequently criticised for the power imbalance between large international NGOs and smaller local, or ‘national’, organisations, INSO has tried to overcome the barriers the latter faces and provide them with critical information about the contexts in which they operate. The INSO also provides security risk management training and support for crisis management.

But USAID accounted for about 37 per cent of INSO’s global budget, says Anthony Neal, its Director of Policy, Advocacy and Communications. As a result, the organisation has had to ‘reduce both in terms of services and the footprint that we have,’ he says. INSO won’t be able, for instance, to provide the same level of training as it previously did, and in some regions the organisation has consolidated sub-offices into singular coordination hubs.

Still, Neal says, it could have been worse. INSO made decisions soon after President Trump’s executive order on the assumption that the funding wouldn’t be returning and so has been able to maintain country-level service in all current locations. Other NGOs, Neal says, delayed that decision-making and are now in a more difficult position.

Contingency planning and emergency response will also probably be impacted. Where aid workers might have previously been assured of the availability of air capacity to remove them from a dangerous situation, this safety net may now be uncertain. Since USAID’s Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance was a major donor to the UN’s Humanitarian Air Service, its absence could result in a reduction of capacity in this area.

In terms of options now open to NGOs, Neal says they may have to come together to try to put standby aircraft in place. However, this would be ‘prohibitively expensive for many NGOs,’ he says, and therefore they will be ‘looking at more road evacuations, which have a different set of risks.’ Indeed, road transit is the geographical location that offers the most risk, with 39 per cent of attacks and confinements since 2019 occurring while workers were in-transit, according to INSO data.

There’s also concern for the mental health of humanitarian workers. A 2024 research study led by Humanitarian Aid International found large gaps in the implementation of mental health support across the sector, and that its availability and quality vary widely and is less likely to be available to local staff. Insurance is another challenge, with many policies not covering war zones or mental health issues.

Aid’s uncertain future

It’s difficult at present to determine exactly where foreign aid is heading, but many commentators agree that things aren’t going to return to the way they were anytime soon.

President Trump’s executive order has shifted the goalposts with respect to how significant policy decisions are regarded within the aid sector. Citing the Dutch government’s move to cut back on specific areas of support within their international development policy – namely women’s rights and gender equality – Neal says that a year ago the decision would have seemed momentous. Now, it’s regarded as ‘not as bad as it could have been.’ This shift is problematic, he says, because it suggests that aid isn’t defendable in the same way it previously was.

UGANDA, Kitgum, World Food Programme, distribution of EU aid maize and USAID cans with vegetable oil for internally displaced refugees of the civil war between the LRA and the Ugandan army. 18 September 2008. Joerg Boethling / Alamy Stock Photo.

In the US, the shape of the Trump administration’s future approach to foreign aid is largely unclear, though Sumar says the ‘broad principles and contours have been outlined.’ In March the president’s aides circulated a memo presenting the silhouette of a new foreign assistance architecture. This defines aid as an instrument of US foreign policy and argues that the current structure is too broad and has failed to reduce the dependency of some countries on US assistance. It suggests a streamlining of foreign assistance and an alignment with US strategic interest by absorbing the remnants of USAID into the State Department.

The following month, Secretary of State Marco Rubio confirmed that he would oversee a major overhaul of the State Department, eliminating several offices and consolidating non-security foreign assistance within existing regional bureaus as a way to ‘drain the bloated, bureaucratic swamp.’

‘The details right now are still very murky and unclear as to who would really have authority, which accounts would get saved, how much programming, who gets the final say in decisions,’ says Sumar. These changes would probably also require congressional authorisation and could face legislative and political hurdles before becoming a reality. Sumar highlights that we haven’t really seen Congress take an active role to date, either by exercising their oversight or putting on the legislative brakes. ‘So, in some ways, we’re in uncharted waters,’ she says.

In the meantime, China has begun to capitalise on the absence of the US. But Beijing isn’t able to fill all of the gaps left by the withdrawal of USAID, nor is it interested in doing so, says Faguet. ‘The Chinese are going to fill certain bits of those gaps, the ones they’re interested in, so they will build roads and dams and bridges,’ he says. ‘But they’re not going to do gender empowerment programmes and early childhood development programmes.’

In the short term, Faguet isn’t optimistic that those previously in receipt of USAID funding for social or health-based projects can do much to mitigate the situation. In the past, he says he might have turned to Europe and presented the positive effects of a given project on children, women and health. ‘Then I could count on the Germans or the French,’ he explains. Now, he guesses that the project at hand would simply cease to be, or else he would need to ‘change and start building roads and go to the Chinese.’ It’s cynical, he says, but that’s how extreme the situation is.

In the long term, Ravi doesn’t see the aid industry fully returning to how it was in the pre-Trump era, even if future US administrations restore funding. The structural and philosophical shifts, he says, will probably be permanent.

Out of the ashes, I hope we can rebuild something that’s more resilient, that’s stronger and smarter

Fatema Sumar

Executive Director, Harvard Center for International Development

Still, Sumar hopes that the crisis forces a broader rethink of approaches to aid. Indeed, the sector was the subject of calls for reform even prior to President Trump’s second term, with commentators pushing for a shift from a charity to an investment mindset. Other key areas of contention have included the need to ensure decisions are made in partnership with communities in the local context as opposed to solely driven by governments or aid donors in Western capitals, and a focus on resiliency in areas such as climate and health as opposed to short-term fixes.

‘It’s time to imagine a different way of investing in people and communities that is not with a charity mindset,’ says Sumar, who calls for the industry to consider more innovative financing, such as social impact investing, pension funds, family foundations and public-private partnerships. ‘Out of the ashes, I hope we can rebuild something that’s more resilient, that’s stronger and smarter,’ she says.

Isabelle Walker is the IBA Junior Content Editor and can be contacted at isabelle.walker@int-bar.org

Myanmar case study: a compound crisis

Embroiled in a four-year-long civil war, still reeling from the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic and suffering a 7.7-magnitude earthquake in March, Myanmar’s situation provides an unfortunately acute case study into the impact of the USAID cuts on the humanitarian response to a complex, and compound, crisis.

The first major natural disaster to occur after the USAID decision, Myanmar was already described as a ‘profound “polycrisis”’ in a January report by the UN Development Programme (UNDP), even prior to the aid freeze and earthquake. Political instability, entrenched conflict, economic disruptions, severe human rights violations and worsening environmental degradation had ‘reshaped every aspect of life’, the report said.

The death toll from the earthquake has surpassed 3,700, with 4,800 injured and 129 reported missing according to the AHA Centre, which is coordinating the humanitarian response among Association of Southeast Asian Nations member states.

In 2024, USAID spent $240m in Myanmar and the US funded around a third of the country’s multilateral humanitarian assistance. But the number of USAID programmes in Myanmar has fallen from 18 to three since early 2025. In response to the earthquake, the US sent a team of three advisers to the disaster zone. A typical response from the US might previously have included around 200 rescue workers, along with specialist equipment and sniffer dogs.

US Secretary of State Marco Rubio responded to accusations that Washington was unable to help after the tragedy by saying that the US is ‘not the government of the world’ and the country had to balance global humanitarian rescue work with ‘other needs’ and ‘other priorities’ that were in its national interests. ‘There’s a lot of other rich countries in the world, they should all be pitching in,’ he added.

And they have. While American flags were largely absent, brightly dressed Chinese and Russian search-and-rescue teams were photographed pulling survivors from the rubble. Meanwhile, India established a field hospital in Mandalay. Assistance has also been provided by the UK and the EU.

Still, the US withdrawal has left a noticeable void in both the earthquake response and the broader humanitarian infrastructure within Myanmar. And the cost of this absence is human suffering. The freeze in aid has led to the closure of female crisis centres for victims of trafficking and domestic violence, while PEPFAR clinics have been forced to shutter and the World Food Programme struggles to meet demand.

During a press conference in March, the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, Thomas Andrews, said the ‘sudden and chaotic withdrawal of support’, principally from the US, was having a ‘crushing impact on the people of Myanmar.’ Hopes that other nations might step up to fill in the gaps are being dashed by aid budget cuts around the world, he added.

Andrews said it was fair for the US to question why the responsibility for humanitarian responses isn’t more equitable. But, he said, ‘this is the worst possible way to go about it and it just makes it very clear to me that this is not about burden sharing. It is politics in its worst form, and it’s sacrificing human lives to make a bad political point.’