The great regression

Jennifer Venis, IBA Multimedia JournalistTuesday 15 December 2020

The rights of half of the world’s population are threatened thanks to the Covid-19 pandemic and a state-driven backlash against gender equality. Global Insight explores recent regressions in the rights of women, the connection to the rise of nationalistic populism, and how best to counter this rollback.

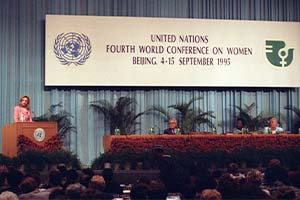

This was supposed to be a landmark year for gender equality. Twenty-five years ago, a ground-breaking blueprint for advancing women’s rights was agreed by representatives of 189 governments at the United Nations Fourth World Conference on Women.

This blueprint, the Beijing Platform for Action and Declaration, encapsulated comprehensive commitments in 12 key areas. Unfortunately, despite these commitments securing 274 legal and regulatory reforms in 131 countries, much work remains to be done.

Women still only have 75 per cent of the legal rights of men worldwide, according to the UN, and their lives are threatened by restricted healthcare and gender-based violence.

Women are still excluded from decision-making processes, climate talks and peace negotiations, while men make up 75 per cent of parliamentarians worldwide. UN Secretary-General António Guterres recently lamented that ‘women continue to have to fight for their voices to be heard, despite the mountain of evidence on the correlation between women’s participation and the sustainability of peace.’

The world is also missing out on the $172tn in human capital wealth that the World Bank estimates closing the gender pay gap would generate.

Hilary Clinton delivers an address at the UN Fourth World Conference on Women, 1995

But with labour force participation stagnant at 31 percentage points over the past 20 years, the pay gap may persist for another 150 years.

Now, the Covid-19 pandemic is threatening to wipe out decades of limited gains. In Justice for women amidst COVID-19, organisations, including the agency UN Women, warn that the pandemic ‘will push back fragile progress on gender equality, including in relation to reversing discriminatory laws, the enactment of new laws, the implementation of existing legislation and broader progress needed to achieving justice for all.’

A shadow pandemic

An April UN Policy Brief highlighted that ‘women will be the hardest hit by this pandemic but they will also be the backbone of recovery in communities. Every policy response that recognises this will be more impactful for it.’

Yet, according to UN Women’s report From insights to action: Gender equality in the wake of COVID-19 (the ‘Insights Report’), less than one in five labour market and social protection measures enacted during the pandemic have been gender-sensitive – despite women making up a significant proportion of frontline healthcare workers. The oversight is costing women their livelihoods and their lives.

Women's Strike movement protest against anti-abortion law, Warsaw, Poland, 30 October 2020

Covid-19 has turned back the clock on many women’s economic opportunities. Winnie Tam, Diversity and Inclusion Officer of the IBA Asia Pacific Regional Forum and Head of Chambers at Des Voeux Chambers, emphasises that access to childcare has been key to enabling women in Hong Kong to participate in the workforce pre-pandemic.

Yet, in the UK, Joeli Brearley, founder of campaign group Pregnant Then Screwed, declared women the ‘sacrificial lambs’ of the country’s economic contraction, with 51 per cent lacking the necessary childcare to enable them to work.

Covid-19 has also closed educational institutions worldwide and many girls will never return. Education will be curtailed by lack of access to digital resources, by growing burdens at home, and by rights violations like child marriage. Research by the UN Population Fund and partners suggests an additional 13 million child marriages will take place that otherwise would not have occurred between 2020 and 2030.

Girls unable to break cycles of poverty and disrupt gender norms may also lose their lives. Organisations, including the World Bank, expect a rise in adolescent pregnancies, and complications from pregnancies and childbirth are already the leading causes of death for adolescent girls globally.

In June, the World Health Organization reported that even a ten per cent reduction in sexual and reproductive health services could lead to 29,000 additional maternal deaths within just 12 months. But UN Women’s Insights Report highlights that in Azerbaijan, 60 per cent of women have faced difficulty accessing gynaecological and obstetric care during the pandemic.

Many governments did not ensure this healthcare was classed as essential to continue through the pandemic, and some imposed further restrictions.

Women’s lives have also been threatened by a ‘shadow pandemic’ of increasing gender-based violence, including domestic abuse. In February, Guterres said levels of femicide ‘could be likened to a war zone’ in some places, and since then femicide has increased exponentially – Latin America, for example, has reportedly seen a 20 per cent increase in 2020 so far.

Yet, while Mexico saw more women murdered in April than in any other month on record, its government cut the budgets of women’s shelters.

Seeking justice for gender-based violence was already challenging. Catalina Santos, Pro Bono Initiatives Officer of the IBA Latin American Regional Forum and partner at Brigard Urrutia, says ‘there are important barriers when reporting cases of femicide or sexual abuse. Latin American culture, historically a male culture, has managed to normalise or tolerate these situations, and this is the reason why women are afraid to go to the authorities.’

She adds that even where gender-based violence is reported, in many cases there is impunity or penalties lacking severity.

Backlash

While the pandemic has been exacerbating these existing inequalities, in some places women’s rights have been eroded by other means.

In the United States, for example, several states that had tried but failed to ban abortion in 2019 found that Covid-19 offered an opportunity to restrict access by deeming such healthcare non-essential.

In October, Poland’s Constitutional Tribunal declared abortion for foetal, including fatal, abnormalities – the grounds on which 98 per cent of abortions were sought in Poland in 2019 – to be unconstitutional. Aleksandra Stepniewska, counsel at WKB lawyers in Warsaw, suggests ‘maybe it’s not without reason that the Constitutional Tribunal issued this judgment now.’

She notes those who issued the decision must have envisaged that it would lead to demonstrations at a time when there are pandemic-related restrictions on protests.

These countries are not alone. At the Beijing Declaration (virtual) anniversary event in October, delegates warned that women’s rights, alongside the human rights from which they are indivisible, are sliding back worldwide in part due to a significant backlash against gender equality.

Charlotte Gunka, Co-Chair of the IBA Crimes Against Women Subcommittee, believes this backlash is deeply connected to the rise of nationalistic populism, and the corresponding resurgence of extreme religious views being incorporated into state policies.

In the US, the Trump administration has appealed to conservative religious groups by explicitly denying abortion rights – despite such rights being protected by the US Constitution and international human rights frameworks.

US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s Commission on Unalienable Rights, created in July 2019, emphasises the US’s ‘religious hegemony’ and calls abortion and marriage equality ‘political controversies’. It seeks to establish a hierarchy of rights and declares that ‘US foreign policy can and should consider which rights most accord with national principles and interests at any given time.’

Even if – as expected – the incoming Biden administration throws out the work of the Commission and recommits to gender equality, damage has already been done on an international level.

Wade McMullen, Senior Vice President of Programs and Legal Strategy at Robert F Kennedy Human Rights, says ‘there is now a model put forth in the international community, via a very powerful and influential international actor in the US, endorsing cultural relativism and politicising rights claims that have been well established through the international human rights project.’

There is now a model put forth in the international community, via a very powerful and influential international actor in the US, endorsing cultural relativism

Wade McMullen

Senior Vice President of Programs and Legal Strategy, Robert F Kennedy Human Rights

Further, President Trump was successful in securing a 6-3 conservative majority on the Supreme Court for decades to come by appointing Justice Amy Coney Barrett after the death of the Court’s stalwart defender of women’s rights, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

Akila Radhakrishnan, President of the Global Justice Center, is concerned that such a politically biased Supreme Court could spell disaster for many rights that were already on tenterhooks. ‘The Supreme Court doesn’t look like it’s going to stand up for women’s rights anymore. And that’s terrifying,’ she says.

‘Gender ideology’

In its report Gender equality: Women’s Rights in Review 25 years after Beijing, UN Women notes that trends towards economic instability, increased displacement and environmental degradation have ‘coalesced in the rise of exclusionary politics, characterised by misogyny and xenophobia. Forty years after the adoption of the Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination against Women … women’s rights are being eroded in the name of a return to “traditional values”, and the institutions created to advance gender equality are being undermined.’

In late July, Poland’s Justice Minister Zbigniew Ziobro announced his government’s intention to withdraw from the Council of Europe’s Istanbul Convention, the world’s first legally binding instrument to prevent and address gender-based violence. Ziobro argues that the Convention ‘takes aim at family, marriage and the currently functioning social culture when it comes to comprehending gender.’

Because the Convention defines gender as ‘socially constructed roles’, separate to biological sex, the Polish government sees the Convention as promoting LGBTI rights through a ‘gender ideology’. An October 2019 survey by Ipsos found that a majority of Polish men under 40 see the ‘LGBT movement and gender ideology’ as Poland’s biggest threat in the 21st century.

Stepniewska says the government believes ‘the Convention’s aim and application would provide for the destruction of the structure of the Polish society.’

To replace the Istanbul Convention, Poland has sought to create a regional treaty that would bolster the rights of ‘traditional’ families, which critics believe will harm LGBTI people and reproductive rights. In July, Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki announced that Poland’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs has been given a ‘clear assignment concerning cooperation with other countries, to come up with appropriate provisions which are not imbued with any worldview elements – and therefore doubts – related to the moral revolution that some want to impose on us.’

‘They would like to defend the status quo,’ Stepniewska says. ‘To some extent we may ask why they are so afraid of equal partnership in families and generally in society.’

Poland is not alone in taking issue with a ‘gender ideology’. The concept, which originates in the 1990s, has gained such prominence in Europe and the Americas that it was addressed by the European Union. In 2018, the European Parliament commissioned a report, Backlash in Gender Equality and Women’s and Girls’ Rights, and a corresponding resolution was adopted in the European Parliament in early 2019.

The report connects equality backlash ‘to a significant degree with intensifying campaigning against so-called “gender ideology”’. One academic interpretation is that ‘the concept of gender ideology has become “symbolic glue,” uniting many groups and their critiques of numerous issues: modernity in its postmodern form, the identity politics that they identify with gender equality, same-sex marriage, some women’s rights issues (such as sexual and reproductive rights), sex education, challenging restrictive traditional gender roles, and the instability of the post-2008 crisis world.’

The rise of nationalism and populism seems to be a reaction to what is viewed as a threat to the hegemonic male monopolisation of power

Akila Radhakrishnan

President, Global Justice Center

For Radhakrishnan, ‘the rise of nationalism and populism seems to be a reaction to what is viewed as a threat to the hegemonic male monopolisation of power in any particular context.’ She argues, ‘the thought of an equal pluralistic world terrifies certain people, and this is the reaction, the dying grasp of the patriarchy clinging to the past.’

Forward march

In the face of that, ‘we have to be strategic and creative’ to achieve gender equality, Radhakrishnan says.

She believes this is a moment to learn from pioneering women and points to Justice Ginsburg’s legacy of fighting legal discrimination on the basis of sex before she joined the Supreme Court. Radhakrishnan says, ‘there’s so much inspiration when you look at how it is that, in that era, when all of these precedents didn’t exist yet, the ideas were being formed and the arguments were being created.’

For Stepniewska, ‘the crucial thing is education. Children should be taught from the beginning that they have freedoms and rights. Family should be about partnership and there should not be rigid divisions, and this sense of freedom and the possibility of choice should be taught to children.’

She adds that legal guarantees for freedoms and rights and equality won’t be effective if they are not ‘internalised by people’. Stepniewska believes that to have legal solutions that guarantee more gender equality in Poland would take political will, which may take a cultural change and a new government.

The crucial thing is education. Children should be taught from the beginning that they have freedoms and rights

Aleksandra Stepniewska

Counsel, WKB lawyers

Overcoming cultural and structural barriers to social change is a challenge everywhere. Diana Hamade, Vice-Chair of the IBA Arab Regional Forum, says family laws that prevent women possessing their children’s passports – because men are seen as the children’s guardians, while women are custodians – have been particularly problematic during the pandemic and remain unaddressed in the United Arab Emirates.

Elham Ali Hassan is the Conference Quality Officer on the IBA Arab Regional Forum and is based in Bahrain. She notes that ‘culture and religion are in some aspects the main barriers impeding the protection of human rights legislations, especially in respect of abortion, recognition of children born outside of wedlock, and LGBT rights.’

But she and Hamade highlight that change has been forthcoming in the region. In November, the United Arab Emirates amended family laws to better protect the rights of women, including moving to treat ‘honour crimes’ as any other crime, without reduced sentences.

The UN believes ‘the Covid-19 pandemic provides an opportunity for radical, positive action to redress long-standing inequalities in multiple areas of women’s lives, and build a more just and resilient world.’ To reach that world, in its Women’s Rights in Review 25 years after Beijing report, UN Women outlines four universal catalysts for change.

First, supporting women’s movements and leadership, particularly as UN Women’s Insights Report finds ‘in countries with women at the helm, confirmed deaths from Covid-19 are six times lower.’

Second, harnessing technology to create more opportunities for women and to close the gender digital divide, to enable the delivery of public services and to mitigate and adapt to climate breakdown.

Third, to match commitments with resources, given the percentage of development resources devoted to gender equality languishes at less than five per cent while global annual military expenditure has reached $1.82tn.

Finally, to ensure ‘no one is left behind’, which requires intersectional, disaggregated data and analysis. In the legal profession, the IBA’s Legal Policy & Research Unit is building a gender project that will, over the next decade, retrieve and analyse data on women’s progress in the profession.

UN Women notes feminist leaders are clear that gender equality is inseparable from intersectional issues like racial justice, workers’ rights, climate justice, LGBTI rights, corporate accountability and more. The Insights Report states that addressing structural discrimination with an intersectional approach can shape ‘an alternative vision of a future where women’s rights are at the centre of a better world for all.’

That message has been clear in the high involvement of women in recent protest movements worldwide – in the Black Lives Matter protests, climate justice globally and pro-democracy movements, such as in Belarus and in Poland.

For everyone

Despite the pandemic and severe rule of law concerns that make fighting the backlash in Poland particularly challenging, this autumn the Polish Women’s Strike movement has come out in full force and marshalled the largest demonstrations the country has seen in decades.

In 2016, the Women’s Strike successfully forced parliament to backtrack on a total abortion ban that would have imprisoned women. Women’s voices have undeniably been powerful again, forcing the Polish government to delay publishing this October’s Constitutional Tribunal ruling in the Official Journal, which would be necessary for it to take effect.

Stepniewska highlights that ‘this is not a perfect solution’, raising its own rule of law concerns regarding the binding force of the Constitutional Tribunal judgments and the Tribunal’s legitimacy.

Stepniewska adds that the Women’s Strike is ‘not only about women, but we want to have a Poland for everyone, without discrimination. We don’t want to have political parties which will promote fascist or nationalist ideas. We want to build a civil society based on solidarity and respect for others.’

Many other groups unhappy with the government, its abandonment of the rule of law and control of the courts have joined the protests. The Women’s Strike movement have now set up a Consultative Council to develop ‘a way out of the collapse in 13 key areas’, coordinating many civil society organisations.

Radhakrishnan says there is a great amount of inspiration to be taken from this movement, alongside recent movements in Africa, Asia and South America, which have moved the protection of women’s rights forward in their own countries through organising, protest, advocacy and litigation.

She is also inspired by the climate activism of youth movements worldwide. ‘They have come out unabashedly in favour of massive reform and said “we do not accept your limits”’, she says.

One of the reasons that she believes reproductive rights have become so vulnerable in the US is because the conversation around rights is not moving forward. ‘As a movement’, she says, ‘we spend so much time ourselves stigmatising abortion instead of asking for what we need. The way that advocacy has formed around the issue, focusing on incremental change and justifying abortion for set reasons has made the right vulnerable to attack in the long-term.’

‘Maybe now’s the time to blow the framework open and be unapologetic about what we’re asking for. We don’t need to build back to the existing framework’, she says.

Justice Ginsburg once lamented that Roe v Wade – a 1973 Supreme Court ruling that declared abortion a constitutional right – guaranteed abortion through a privacy framework instead of an equality framework. Radhakrishnan says this means, ‘we don’t have fundamental equality scrutiny of these issues that are clearly matters of gender equality.’

Forty-five years on from Roe, Radhakrishnan says we should be asking how ‘we attack this larger framework of restrictions and bring forth a rights regime that protects all of the different components of what it means to have bodily autonomy and control, including how that plays into the ability to afford access to an abortion.’

We should never believe that a right that is acquired can be taken for granted, because history shows that it can, in a very dramatic way, shift

Charlotte Gunka

Co-Chair, IBA Crimes Against Women Subcommittee

Gunka calls for women to fight for their rights. She echoes Radhakrishnan, noting, ‘We always try to put forward justification. We don’t have to justify the fact we want bodily autonomy’.

When women have, unapologetically, raised their voices, they have historically achieved great change – whether securing suffrage 100 years ago, ensuring every femicide is counted in Argentina in 2015, or securing driving rights in Saudi Arabia in the face of imprisonment.

‘We need to stand up … and fight for our rights as human beings,’ Gunka adds. ‘We should continue to put these issues forward,’ she says, warning, ‘we should never believe that a right that is acquired can be taken for granted, because history shows that it can, in a very dramatic way, shift.’

Jennifer Venis is Multimedia Journalist at the IBA and can be contacted at jennifer.venis@int-bar.org

Header pic: People protest against the ruling by Poland's Constitutional Tribunal that imposes a near-total ban on abortion, in Warsaw, Poland, 26 October 2020. The banner reads: ‘Women on strike’. REUTERS/Kacper Pempel