Asean: showing faith in a single market

After 20 years of talks, the Asian equivalent of the EU has finally become a reality. Whether it succeeds or fails is likely to depend on international free-trade agreements.

Margaret Taylor

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) made history at the end of 2015 when its ten Member States came together to create a single economic bloc inspired by the European Union and designed to make the region one of the most powerful in the world.

Two decades in the planning, the blueprint for the Asean Economic Community (AEC) promised the free flow of goods, services, investments and skilled labour as well as the freer flow of capital across the region, with the long-term aim being to allow Asean to line up next to China and India as one of Asia’s great superpowers. Unsurprisingly, the initiative was hailed by its members as ‘a major milestone in the regional economic integration agenda in Asean’, with the Asean Secretariat stressing the opportunities presented by an integrated market valued at $2.6tr.

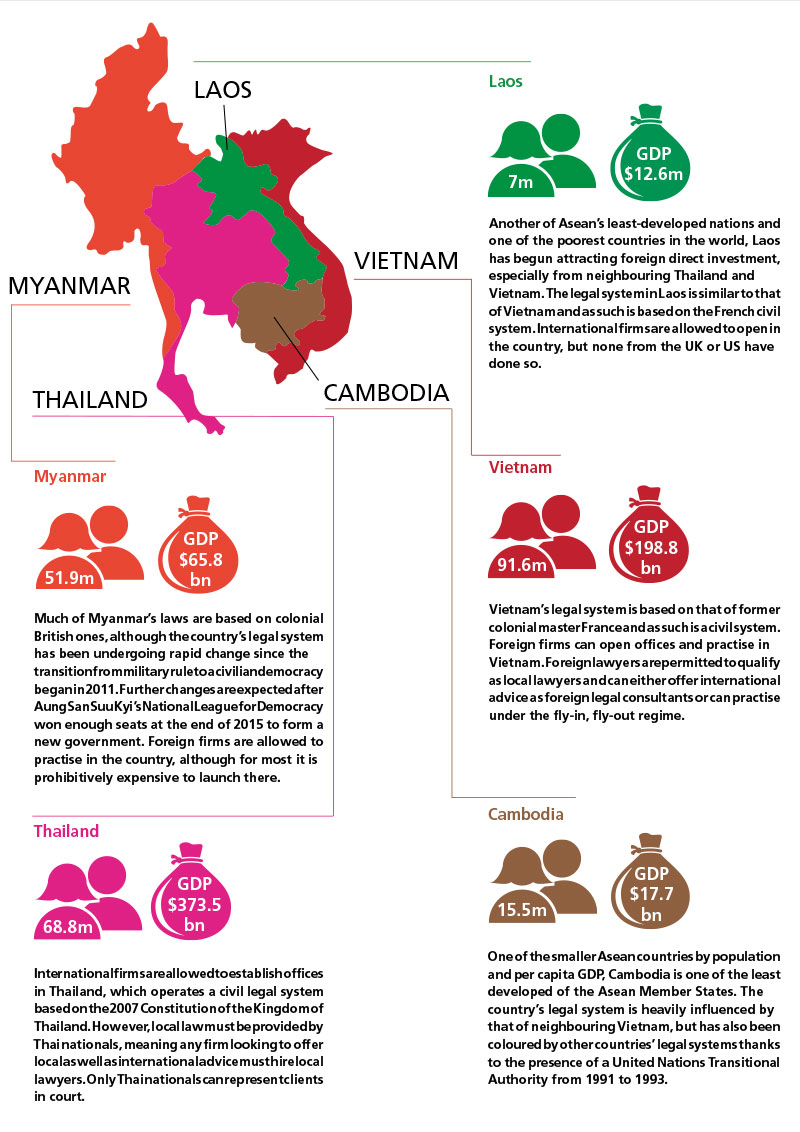

Yet in reality, the failure of every Member State to meet the AEC’s integration timetable means much of the project’s promise is yet to be fulfilled, with the region still some way off being able to claim its crown as the seventh largest economy in the world. Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam, for example, have been given more time to lift the tariffs necessary to make the region a true free-trade area while the free movement of people will, according to Andrew Ong, a partner at Rajah & Tann in Singapore, ‘probably be the last bastion along the road to free-trade utopia’.

World’s seventh largest economic bloc

For Ameera Ashraf, a partner at WongPartnership in Singapore and Senior Vice Chair of the IBA Asia Pacific Regional Forum, being the seventh largest economic bloc in the world would theoretically ‘give the AEC significant bargaining power in global markets’, but at this stage the AEC’s benefits remain theoretical.

Part of the problem, says Ong, is that the 10 countries that make up Asean – Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam – are so different in political, cultural and economic terms that it was always going to be difficult for them to be on the same page when it came to full integration.

‘Different countries will benefit differently from free trade,’ he says. ‘If you had $10 and I had $10 and we know that free trade will bring us another $10 collectively, but out of that amount I’m going to get $7 and you’re going to get $3, would you do the deal? Some people will say $3 is better than nothing, others will say it isn’t quite fair. At a treaty-country level both politicians and bureaucrats are grappling with those philosophical issues when trying to meet a certain timeline or commitment to lower all agreed trade barriers. No one wants to be accused of selling out their country.’

Really the AEC has been a work in progress since the various countries committed to Asean in 2002

Chew Seng Kok

Chairman, ZICOlaw Network

Yet Chew Seng Kok, chairman of the Malaysia-headquartered ZICOlaw Network, says that focusing on where individual countries were at on the date the AEC launched misses the point, with the proof of the region’s potential lying in the progress it has made since the community was first mooted.

‘Really the AEC has been a work in progress since the various countries committed to Asean in 2002,’ he says. ‘Before December 2015 there were a series of steps and initiatives to try to bring the AEC together – people were working towards it but they weren’t sure it was going to happen. Now it has happened a lot of things can take effect. The real question is not so much what has happened since launch, but what has happened since the announcement – and that’s significant.’

Martin Desautels, managing partner of Cambodia-headquartered regional firm DFDL, agrees, noting that there has been a ‘mental shift’ in how companies approach the Asean region. The last few years in particular have seen enterprises operate on a more regional than country-by-country basis. The fact that many import duties have now been eliminated for the intra-Asean trade in goods has helped facilitate this.

‘Now that it doesn’t cost much to transport goods from one country to another we’re seeing supply lines being organised on the level of duties,’ says Desautels. ‘For example, Cambodia exports bikes to Canada and the UK. Parts for the bikes come from Malaysia to Cambodia duty free and [the finished bikes] are then sent to Europe and Canada via the free-trade agreements Cambodia has with them.’

Investment race

On the one hand, this supply-chain scenario is encouraging the more mature Asean countries to pour cash into their less-developed neighbours, with Malaysia investing in the gambling industry in Cambodia and Laos while Singapore is funding hotels and resorts across the region. On the other, the fact that the ten nations come from such different starting points means that Asean members are competing with each other to attract foreign direct investment from outwith the region.

A partner at Baker & McKenzie.Wong & Leow in Singapore, Eugene Lim notes that Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand have all come up with their own incentives as they vie to become the location of choice for international business’s regional headquarters. Singapore, for example, offers a reduced corporate tax rate via its Regional Headquarters Award and International Headquarters Award while the Malaysian Investment Development Authority offers major tax exemptions to so-called pioneer companies.

Singapore, which is by far Southeast Asia’s most developed state, is widely expected to win this race, meaning the most advanced of the Asean countries could stand to benefit most from the integrated market.

Sunil Abraham, a partner at Cecil Abraham & Partners in Malaysia and Co-Chair of the IBA Asia Pacific Regional Forum, points out that regardless of the efforts of Malaysia and the Philippines to establish themselves as financial centres, Singapore will always attract the lion’s share of FDI into that sector because it is already seen as Southeast Asia’s premier financial hub. Similarly, while Malaysia is seeking to place itself at the heart of the region’s car manufacturing industry, it faces stiff competition from Vietnam, which, says Abraham, ‘is known as the Detroit of Southeast Asia’.

Such competition not only creates friction between countries that are supposed to be working together, but serves to delay the region’s integration timetable further as Asean’s less-developed states strive to get on a more level pegging with its leaders. ‘Countries like Laos, Vietnam and Myanmar are looking for investment into the country first and foremost then they’ll look at integration with the rest of Asean,’ says Abraham.

In addition to competition between the Asean Member States, the protectionist stance being taken by some of its governments and the Asean Secretariat’s unwillingness to intervene is also hampering the progress of the AEC.

Cynthia Pornavalai, a partner at Tilleke & Gibbins in Thailand, notes that Thailand in particular still has an issue with protectionism, with the situation not likely to change in the near future. ‘The trade in goods is already very competitive, but what we’re working on now is the trade in services,’ she says. ‘That has been a success in Singapore, which has a lot of economic freedom, but a lot of the other countries still have a lot of protectionist policies. Thailand is one of them – the service sector here is closed to foreigners. There will be liberalisation of trade and services under Asean because we have to commit to that and a number of service industries have been opened up by parliament but there’s still lots to go into in terms of service sectors.’

Qualified freedom

It is in the individual countries’ unwillingness to embrace the free movement of people within the region that protectionism arguably finds its most extreme expression. So far it has been agreed that people working in just a handful of professions can move freely across borders, with doctors and engineers among them. However, Pornavalai points out that the barriers have been set so high that few will actually be able to take advantage of the change. ‘The idea is that a person from one Asean country can work in another, so doctors [from elsewhere in the region] can practise in Thailand, but they would have to first take the medical exam in Thailand in the Thai language,’ she says.

For countries such as Myanmar, which has a largely uneducated and untrained labour force after decades of repressive military rule resulted in a neglected educational system, this presents a particular paradox. Lucy Wayne, managing partner of Yangon-based Lucy Wayne & Associates, says that while the country is in need of skilled foreign labour to help train its own workforce, there are concerns that domestic industries may not be given time to develop if non-Burmese are allowed to set up shop there. ‘If a foreign accountant can come here and practise as an accountant then how are the Myanmar accountants going to develop?’ she says. ‘Myanmar does stand to benefit as long as other countries recognise that they do need to train up the Myanmar people as part of their entry into the country and not just bring people from their own region.’

Another issue is that for the free movement of people to work on an equitable basis there would have to be harmonisation of educational and training levels across the region. This would be problematic on one level because, says Ong at Rajah & Tann, ‘sometimes it’s not just a question of qualifications – it’s also the competency with the language. How do you make homogenous something as different as language?’ On another level, getting each Member State to agree on what the homogenising factors should be could ultimately prove impossible.

‘The AEC works on a principle of consensus and non-interference,’ says Ashraf at WongPartnership. ‘Given that it’s an area that is politically and culturally diverse, there may be challenges in realising its vision through consensus.’

Abraham at Cecil Abraham & Partner agrees and points out that even if the Asean region had the will to enforce legislation on its constituent nations, in reality it would be unlikely to have the might. ‘The problem with the AEC is political

co-ordination,’ he says. ‘The Asean budget is only around $14m – we’re talking about an economy that would be the seventh largest in the world, but it could have some issues enforcing policies.’

Trans-Pacific influence

Bearing all this in mind, could the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), which four Asean countries (Brunei, Malaysia, Singapore and Vietnam)have signed up to and five others (Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, the Philippines and Thailand) are interested in, ultimately prove the making of the AEC? A free-trade agreement between 12 Pacific Rim countries, the TPP was signed at the beginning of this year and will come into effect when it has been ratified by all 12 governments.

Lim at Baker & McKenzie.Wong & Leow calls the TPP ‘a truly revolutionary agreement as it connects Asian counties to North American and Latin American economies, giving access to key markets in the US and Canada’. Crucially, unlike the AEC, the TPP is a binding agreement.

While there are concerns that the TPP will allow the likes of the US and Japan to enter the Asean markets that are also signatories to the agreement, Chew at ZICOlaw says the export nature of the Asean signatories means that the positives will ultimately outweigh the negatives. ‘Malaysia and Vietnam will be the real beneficiaries because they have strong export potential and they’ll have a chance to export to the US, Australia and Japan,’ he says. ‘The TPP has pulled out another layer of globalisation within a legal framework. That reinforces the liberalisation trend but builds in protection against liberalisation.’

While Chew believes that the Asean countries that did not sign the TPP will lose out, the fact that four Asean states will be able to serve as a gateway to countries with large and wealthy consumer bases via an agreement whose provisions are obligatory should help bring some order to the AEC.

The AEC [will have] significant bargaining power in global markets

Ameera Ashraf

WongPartnership; IBA Asia Pacific

Regional Forum

Desautels at DFDL says that with Asean supply lines likely to end in countries such as Vietnam ready for supply to other TPP nations, greater AEC co-ordination in the vein of the Malaysia-Cambodia bike scenario is likely. This is because while it may not be entirely attractive to be a link in a value chain where consumption of the end product is going to be limited, it is an another thing entirely if that product has a route into the largest economy on earth.

Add in the fact that the whole of Asean is also part of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) negotiations, which propose to bring down trade barriers between Asean and Australia, China, India, Japan, South Korea and New Zealand and suddenly there is a link to the second largest economy in the world too. Like the TPP, the RCEP has not yet come into force, but when it does the benefits could be huge.

As Ong at Rajah & Tann says: ‘I think Asean realises that the AEC will be far less valuable to the world – and to itself – without RCEP and TPP.’ In other words, it is not until the RCEP and TPP are fully operational that the true benefits of the AEC will be seen.

Margaret Taylor is a freelance journalist and can be contacted at mags.taylor@icloud.com