UK Supreme Court: unanimous and unequivocal in righting rule of law wrongs (Global Insight Oct 2019)

Ruth Green, IBA Multimedia Journalist

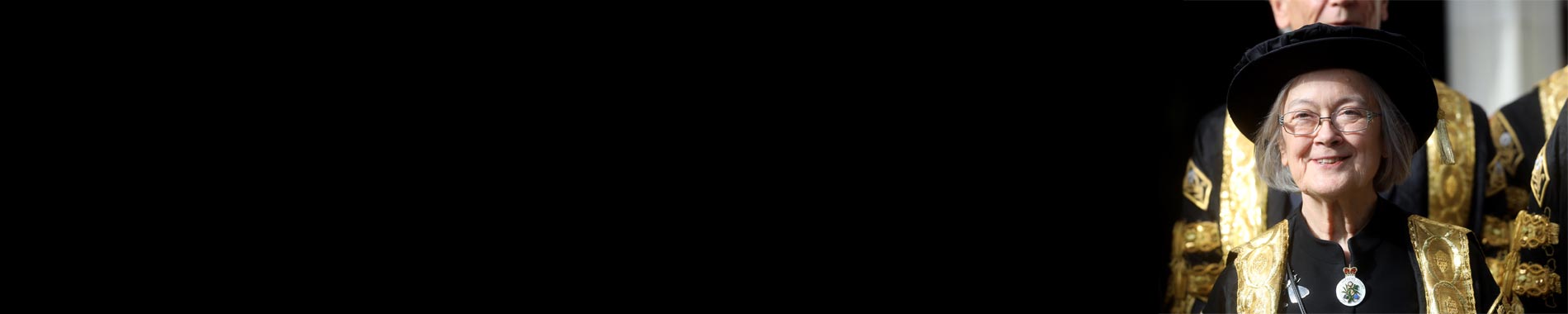

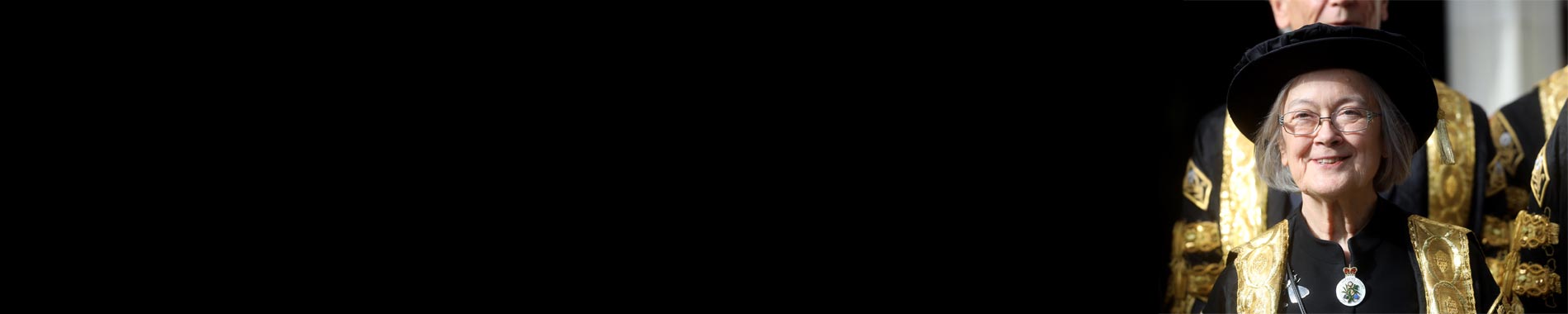

UK Supreme Court President, Baroness Hale of Richmond © Gavin Rodgers/Alamy

The attempted prorogation of the UK Parliament at a time of national crisis opened a Pandora’s box of constitutional, democratic and rule of law issues – all of them more important than Brexit itself.

'The Court was wrong’ came the unrepentant rallying cry of UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson to Members of Parliament the day after 11 Supreme Court justices had unanimously ruled his government’s decision to suspend Parliament ‘unlawful’. The Leader of the House of Commons, Jacob Rees-Mogg, had already sparked outcry by describing the ruling of the Supreme Court as a ‘constitutional coup’.

It was, of course, anything but, and the government’s contentious lack of contrition jarred with the measured authority of the UK Supreme Court’s President, Baroness Hale of Richmond. On 24 September, she matter-of-factly concluded that the attempted suspension had stopped Parliament carrying out its ‘constitutional functions without reasonable justification’. Hale emphasised that the Court was ‘solely concerned with the lawfulness’ of the attempted prorogation – and not about when, or on what terms, the UK would leave the EU – adroitly averting criticism that the justices were being drawn into political debate.

This unprecedented period in British political, parliamentary and governmental history was triggered by then Prime Minister David Cameron’s decision to hold a referendum on the UK’s membership of the EU in 2016. But, three years later (and with the question of whether to leave or remain as divisive as ever), far more important issues are at stake: democracy and the fragile yet essential balance that lies at the heart of the UK constitution – the separation of powers between the legislative and executive branches of government and, importantly in the current context, an entirely independent judiciary.

It was only in October 2009 that judicial authority in the UK was transferred away from the House of Lords to make way for the Supreme Court – a new final court of appeal that was overtly and transparently independent from Parliament. Nevertheless, the UK, with its uncodified constitution, remains heavily reliant on trust, confidence and the willingness of everyone involved to behave according to convention. The government’s attempt to prorogue Parliament drove a coach and horses through all of this. Hence a very straightforward decision for the Supreme Court and its 11 independent justices.

Three separate judicial review cases were launched as soon as news broke at the end of August that Prime Minister Johnson was attempting to prorogue Parliament: one in London, brought by businesswoman and campaigner Gina Miller, one in Edinburgh and another in Belfast. High Court judges in both London and Belfast rejected arguments that the courts should intervene. However, Scotland’s highest civil court ruled that the Prime Minister’s attempt to prorogue parliamentary proceedings for five weeks (the longest period since 1945) was motivated by the ‘improper purpose’ of ‘stymying Parliament’. The three judges ruled the decision as ‘unlawful’, thereby deeming it unconstitutional and a direct contravention of the rule of law.

It is simply replacing what ought to have happened by convention by law in circumstances where the government has tried to kick away the conventions

Lord Jonathan Sumption

Former Supreme Court Justice

On 17 September, the Supreme Court heard the government’s appeal against the Scottish case and Miller’s appeal against the London ruling. It was only the second time a panel with the maximum 11 justices has been appointed, a clear indication of the constitutional and national significance of these cases. The first occasion was for Gina Miller’s Article 50 case two years previously, which served as a reminder of the sovereignty of Parliament.

An even number of justices was avoided to prevent potential deadlock. This proved unnecessary as the Court was unanimous and, on 24 September, the justices handed down their unequivocal judgment.

They found in favour of the Scottish court and ruled that ‘the extent of the power to prorogue’ was a justiciable matter. Based on the evidence put before the Court, the judgment said it was ‘impossible to conclude… that there was any reason – let alone a good reason’ for the Prime Minister to advise the Queen to prorogue Parliament for five weeks. It consequently ruled that the prerogative of prorogation was ‘unlawful… null and of no effect’.

Parliament resumed the following day. The suggestion that the ruling was wrong and of a ‘constitutional coup’ were quickly rebutted, both within the government itself – by Attorney General Geoffrey Cox – and by leading constitutional experts, including former Supreme Court Justice, Lord Jonathan Sumption, who confirmed that the Court’s ruling reinstated ‘parliament at the heart of the decision-making process’. He also made clear that it was ‘not undermining democracy at all, nor is it a coup, it is simply replacing what ought to have happened by convention by law in circumstances where the government has tried to kick away the conventions’.

These cases have emerged against a fraught backdrop beset by concerns over how the UK conducts elections and referenda. Controversies surrounding the 2016 referendum are well documented. Nevertheless, when Johnson took over as Prime Minister on 24 July, he appointed Dominic Cummings as his special political adviser. Given Cummings was Campaign Director of Vote Leave, which was fined £61,000 for multiple breaches of electoral law in the run-up to the referendum, and was subsequently found in contempt of Parliament, it is understandable that his appointment is being questioned by those who view it as inimical to the rule of law.

The judges in the Scottish case were lauded by one newspaper as ‘Heroes of the People’, a pointed rebuttal of the distasteful front page of an influential UK tabloid newspaper during Miller’s Article 50 case, which labelled the Supreme Court justices ‘Enemies of the People’. Judges should be classed neither as heroes nor as villains. This misrepresents their crucial role as impartial arbiters – in these cases holding the government’s actions up to the appropriate level of judicial scrutiny.

All this takes on an even greater significance, of course, as we witness growing populist forces threatening fundamental aspects of the rule of law such as freedom of expression and judicial independence – both in Europe and around the world. The day after the UK attempted to suspend Parliament, Poland followed suit. In this context, and with the increasingly febrile nature of events triggered by the referendum in 2016, the Supreme Court’s unanimous and unequivocal judgment sends a clear message that, even in the face of such toxic forces, the rule of law can prevail.

Ruth Green is Multimedia Journalist at the IBA and can be contacted at ruth.green@int-bar.org