Venezuela: Currency crisis brings economy to standstill

Meg Weddle

At the end of 2016, President of Venezuela Nicolás Maduro announced the withdrawal from circulation of the 100-bolívar note – Venezuela’s highest form of currency, which has accounted for as much as 48 per cent of all paper money in the country. The decision has pushed the country further into a humanitarian disaster.

The value of the bolívar has plummeted due to the world’s highest inflation rate: currently so high that a sackful of cash is needed to pay for basic items. Venezuela’s exchange rate on the black market has fluctuated between two and four US cents in recent months and roughly 40 per cent of Venezuelans are thought to be without a bank account. The decision to cease the circulation of the 100-bolívar note brought the economy to a standstill.

President Maduro announced that new notes of 20,000, 10,000 and 5,000 bolívars were immediately being pumped into circulation. However, people reported that on depositing their 100-bolívar bills with the bank and attempting to withdraw the higher denominations from ATMs, they were only able to withdraw more of the discontinued notes.

‘‘Suddenly, one day, it was just impossible to pass your credit or debit cards over to pay for whatever you wanted to. This meant the whole system collapsed

‘‘Suddenly, one day, it was just impossible to pass your credit or debit cards over to pay for whatever you wanted to. This meant the whole system collapsed

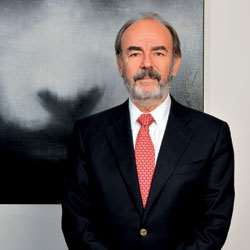

Fernando Peláez-Pier,

Former IBA President; Partner, Hoet Peláez Castillo & Duque, Venezuela

The promise of higher-currency notes being circulated immediately fell through when planes reported to be delivering the new notes failed to arrive. Maduro blamed a ‘sabotage’ campaign by foreign enemies, and was compelled to delay the withdrawal. The three higher denomination notes began to enter circulation in mid-January, effectively releasing more money into an already hyper-inflated market.

Venezuela has ceased publication of inflation data, but the International Monetary Fund estimates that inflation rates could top 1,600 per cent in 2017 and 2,880 per cent in 2018. Venezuela’s strict currency controls and heavy reliance on oil – prices of which have dropped by half since 2014 – are considered to be the root of the inflation problems, yet Maduro’s government has blamed various other sources, including a so-called ‘economic war’ led by the opposition and the US.

A critical scarcity of food continues across the country, in large part due to a reliance on imported goods now beyond affordability. Hans Sydow Guevara, a partner at Tinoco Travieso Planchart & Núñez in Caracas, explains: ‘The shortages of food and medicine are basically the result of corruption, inefficiency and a lack of funds available for Venezuelan internal production. This government has practically killed the private sector in all areas.’

Imported wheat is in such short supply that bakeries are being spot-checked for signs of hoarding. The military, put in charge of ‘food management’, has become one of the largest profiteers from black market trade, selling goods for 100 times their retail price. Some have speculated that the handing over of food distribution to the military was an attempt by Maduro to prevent a possible coup; however, one source suggests there is no need for the military to do so: ‘They have a very strong position, with political and financial power, so do they need to go ahead with a coup? I think there is more interest in removing Maduro from other players with political power than the military.’

The national healthcare system has also collapsed, with people facing acute shortages of medical supplies. Peláez-Pier tells Global Insight that private hospitals are even turning away people who can afford to pay for care, due to a lack of essential implements and medicines. Hospitals have taken in patients on the prerequisite that they source their own medicines: ‘If you follow the different social networks, you find hundreds of messages from people asking for medicine, because you just can’t find them in the pharmacies,’ he says.

As of March 2017, Venezuela has just $10.5bn left in foreign reserves, with a further $7.2bn in debt repayments still outstanding. In early January, Venezuela issued $5bn in new bonds to state-run Banco de Venezuela.

50.1 per cent of shares in CITGO, a subsidiary of Venezuelan state oil company PDVSA, were sold as collateral in the bond operation. Peláez-Pier suggests that the issuance of the bonds may be linked to PDVSA then selling the other 49.9 per cent of its shares in CITGO – which has three refineries and a number of assets in the US – as collateral to Russia, in order to generate the cash necessary to pay different obligations and avoid default. ‘CITGO was a last resort – to make use of one of the assets left to Venezuela,’ he says.

Maduro has repeatedly rejected civil society organisations' requests to bring in humanitarian aid, despite the extreme shortage of supplies leading to civil unrest, crime and violence across the nation, as well as a mass exodus to bordering countries. ‘Since 1999 the military sector has controlled the most important posts in government,’ Sydow adds. ‘The application of the Constitution can no longer be guaranteed. The principal issue for legal practitioners is that there is no rule of law in Venezuela.’

International events reflect Sydow’s concerns: in February, a US resolution was passed unanimously by the Senate expressing serious concern about the crises in Venezuela, and attention now turns to the Trump administration in the hope it will provide support to Venzuela. Options for US policy going forward focus on installing constitutional and democratic order, and strengthening the rule of law, as essential for combating the extreme poverty now affecting over half the population.

Meg Weddle is Content Editor at the IBA and can be contacted at meg.weddle@int-bar.org.