Zimbabwe after Mugabe

Carmel Rickard, Free State

The bloodless transition to a post-Mugabe era brought hope that the country could emerge as a democracy governed by the rule of law. The elections at the end of July suggest otherwise.

Since the elections on 30 July, when Zimbabwe’s ruling party, Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front (Zanu-PF), won an overwhelming majority and its new leader Emmerson Mnangagwa was elected as the country’s President, it has been business as usual for the country’s opposition supporters. They fled house-to-house raids by the military and buried people shot by soldiers in downtown Harare two days after the polls. Members of the main opposition, Movement for Democratic Change, also reverted to what sometimes seems their default activity: litigating against what they say is unconstitutional behaviour by the authorities – this time in a fruitless attempt to challenge election results.

Given past experience, none of this would be considered unusual. However, following last November’s bloodless shedding of long-serving President Robert Mugabe and his key officials, many had high hopes that the elections would indicate a return to more than merely nominal democracy.

International observers monitored the polls, speaking out against the military shootings that left at least six dead. Some also made carefully worded criticisms of Zimbabwe’s Electoral Commission (ZEC), the body officially running the polls, for lack of transparency.

As far as human rights lawyers in Zimbabwe are concerned, however, the ZEC’s transparency problems and the violence unleashed on protesters were almost inevitable. They say that for monitors to have had a proper understanding of the stage on which elections were played out, it would have helped if international legal experts had been involved early on, with a detailed briefing about the legal background.

Justice Mavedzenge, Researcher for the Democratic Governance & Rights Unit at the University of Cape Town, and a practising lawyer and human rights activist, says the elections should be understood through the lens of the law, starting with the 2013 Constitution that set strict standards for how the ZEC should operate. The new constitutionally mandated approach ‘represented a radical departure from Zimbabwe’s old order election management’ and had to be translated into legislation that would undo the previous, partisan way of doing things.

But a rushed election just two months after the adoption of the Constitution meant there was no opportunity to make these changes, so the polls were held under laws acknowledged as in conflict with the Constitution. For example, while the Constitution stipulated the ZEC should operate with complete independence, the old electoral law said ministerial approval was needed for all ZEC administrative regulations.

‘We assumed that after the 2013 polls the new government would make it a priority to sort out electoral reform issues (arising from the Constitution),’ says Mavedzenge. ‘But we were wrong; there was no interest in fixing the laws.’

Zanu-PF fatally delayed the process and rejected all the proposed Electoral Act reforms. ‘Clearly political engagement had failed,’ Mavedzenge says. This opened the floodgates for court challenges as an alternative way to ensure the 2018 elections were constitutionally compliant.

More than a dozen such cases went to court during the year before the elections. In all except one – which was reversed on appeal – the courts rejected attempts to ensure that the elections would meet constitutional standards. For lawyers and human rights activists like Mavedzenge, this was a further indication that many judges put protection of the ruling party above the Constitution.

Another lawyer practising in Zimbabwe, who asked not to be named, says the judiciary was ‘widely viewed as partisan’. For example, the head of the ZEC during the 2008 elections was Judge George Chiweshe, under whose leadership the ZEC held back the results for more than six weeks. This caused enormous suspicion and dissatisfaction compounded by widespread military attacks on civilians. Judge Chiweshe, formerly a brigadier general in the Zimbabwe military, retired from the army when Mugabe appointed him to the bench. His 2010 appointment as High Court President was met by an outcry from opposition parties.

There was no court, no judge, in Zimbabwe that would have been willing to declare the elections flawed

Justice Mavedzenge

Researcher, Democratic Governance & Rights Unit, University of Cape Town

Head of the 2018 ZEC was High Court Judge Priscilla Chigumba, whose impartiality was questioned not least because of photographs, widely circulated on social media, in which she appeared wearing a Zanu-PF scarf identical to those favoured during electioneering by Mnangagwe. Asked for comment by local and international media, Chigumba said the contentious scarf had been a gift from the young woman entrepreneur who designed and manufactured them and that she had accepted and worn it to support the designer.

Harare human rights lawyer Doug Coltart, who was involved in a number of pre-election cases, says that in every application involving the ZEC, even if only indirectly, the Commission opposed efforts to ensure it operated in the transparent, independent way required by the Constitution.

For example, Coltart was involved in a case challenging Electoral Act provisions restricting voter education material by barring foreign funding for voter education and providing that all material had to be officially pre-approved, both of which provisions had been criticised by the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and the African Union. ‘An absurd situation arose in which the Minister of Justice conceded before the court that one of the provisions was unconstitutional and should be struck down, but the court would not do so because of opposition by the ZEC – a body supposed to be impartial and to abide by the court’s decisions on the constitutionality of electoral provisions. As a result, we went into the elections with only the ZEC’s leaflets, no independent material for voter education and massive confusion about aspects of the electoral process.’

In another case, this time brought by Mavedzenge, a blind voter asked for an urgent court order that the ZEC ensure he and others in a similar situation could cast a secret ballot. The judge urged the ZEC to negotiate with the applicant, but then reserved until less than a week before elections when he not only refused the order, but also awarded costs against the applicant. Then the judge left the country for a conference without signing his decision, making it impossible for anyone to appeal before the elections.

Again and again during the run-up to the elections, the courts were approached to hear cases that would have made the polls more transparent and fair as envisaged in the Constitution, but each time these attempts were rejected on narrow, technical grounds even when it was clear the outcome infringed the Constitution.

Mavedzenge says that if events of last November, when Mugabe was removed from office, had been acknowledged as a coup, ‘the world would have understood the position of the judiciary’.

‘Courts cannot function independently after a coup. If the international community had recognised [the events of November 2017] as a coup, they could have anticipated the subsequent behaviour of the judges. It is impossible for there to be rule of law and an independent judiciary in Zimbabwe following this coup.’

All of this exacerbated the problem for opposition parties contesting the election outcome. Given the ZEC’s lack of transparency in almost every aspect of the elections, it was not possible to pierce the opacity of its workings to find evidence, even if it existed. More troubling is Mavedzenge’s view that even if such evidence were found, there was no court, no judge, in Zimbabwe that would have been willing to declare the elections flawed.

In his view, international observers should have looked beyond obvious issues like orderly voting queues. ‘One of the key principles of the SADC Protocol is that the judiciary should be independent. It was not so here, yet the observer missions did not investigate.’ Nor did they familiarise themselves with pre-election cases brought to ensure the polls measured up to constitutional standards.

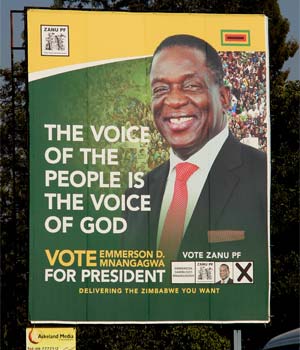

Election billboard shows Zanu-PF candidate, the current President Emmerson D Mnangagwa, in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe, 26 June 2018.

Would it be too late for an international legal organisation to involve itself at this stage? Mavedzenge thinks not: ‘It would be good if they would come, people like the IBA, and do a proper analysis of these things, of the courts and their judgments.’

Unsurprisingly then, given the background of suspicion between the opposition and ruling parties, the panel announced by Mnangagwa to investigate the post-election military shootings has been met with mixed reactions. While Mnangagwa supporters welcomed the names, government opponents said the international panellists appeared suitable but that those from Zimbabwe were ‘compromised’.

Carmel Rickard is freelance journalist. She can be contacted at carmel.rickard@gmail.com