Renewing the Lex Mercatoria

Ruth Green

Forty years after the OECD published its landmark guidelines on responsible business conduct, Global Insight assesses whether the National Contact Points system – established in 2000 - has delivered.

When 83 miners were buried in a landslide at the Tibet operations of China Gold International Resources in 2013, a complaint by the NGO Canada Tibet Committee brought the case to the attention of Canada’s National Contact Point (NCP). Despite extensive efforts by the NCP to bring China Gold – the overseas listing vehicle of the largest gold producer in China, a state-owned enterprise – to the discussion table, the company failed to participate and engage in the consultation process. On publishing its final report just over a year ago, Canada’s NCP took the unprecedented step of imposing sanctions on China Gold under the country’s enhanced Corporate Social Responsibility Strategy for the Extractive Sector, withdrawing Canadian governmenttrade support services from the company. This served as a bold statement not just to extractive companies, but to all companies highlighting the consequences of not participating in the NCP process.

Forty years ago this year the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) established its ‘Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises’, creating what are still largely regarded as the most exhaustive list of government-backed recommendations on responsible business conduct. In June 2000 the OECD set up the NCPs, a ‘soft law’ system specifically designed to ensure governments in every OECD member country are promoting and implementing the guidelines at a national level.

“ NCPs are increasingly recognised as a go-to, non-judicial forum based on ‘soft law’ principles…but they can also have very hard consequences for companies that don’t want to participate

John Sherman

General Counsel, Shift and former Chair of the

IBA Corporate Social Responsibility Committee

While around 7,000–8,000 multinational corporations existed when the guidelines were first adopted, globalisation has seem that number balloon to 50,000, according to the International Labour Organization. The NCP mechanism has also grown as a global forum for remedy for corporate human rights abuses and now spans not only the 34 OECD countries, but also the 12 non-members that have signed up to the OECD’s Declaration and Decisions on International Investment and Multinational Enterprises.

Although the guidelines have been promoting responsible business practices since 1976, the OECD’s decision to formally implement the NCP system in 2000 was a defining moment for the guidelines, says Roel Nieuwenkamp, chair of the OECD Working Party on Responsible Business Conduct. ‘The whole system had been asleep for decades, but got a real boost in 2000 when the NCP system came into being,’ he says. ‘Some NCPs did exist before then but not in a formal way.’

Beyond the call of duty

National Contact Points have been known to go above and beyond their remit. This was most obvious in a case involving Canada’s NCP and Canadian-listed mining and exploration company China Gold International Resources. In 2013, 83 miners were buried in a landslide at the company’s operations in Tibet. A complaint by NGO Canada Tibet Committee brought the case to the NCP’s attention. Despite extensive efforts by the NCP to bring China Gold to the discussion table, the company failed to participate and engage in the consultation process. The NCP took the unprecedented step of imposing sanctions on China Gold under Canada’s enhanced Corporate Social Responsibility Strategy for the Canadian Extractive Sector. This was a bold statement to extractive companies working in or out of Canada to show the consequences of not participating in the NCP process.

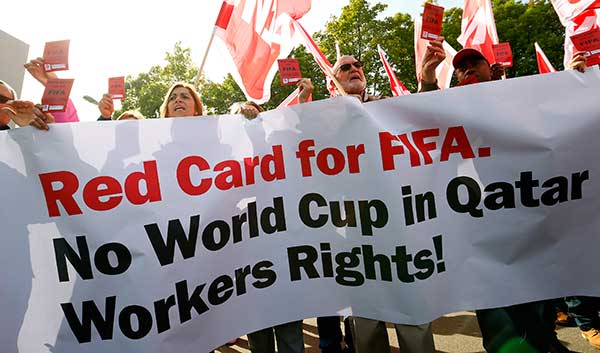

Members of the Swiss UNIA workers union display red cards and chant slogans during a protest in front of the headquarters of FIFA. Qatar has been hit by criticism of its treatment of migrant workers after a report in the Guardian said that dozens of migrant Nepalese workers have died.

In 2011, following more than two years of consultations with NCPs and ministers from both OECD and non-member countries, the organisation revised the guidelines for a fifth time, this time in line with the UN Guiding Principles framework developed by Professor John Ruggie, former special representative of the UN Secretary-General for Business and Human Rights. The revision clarified the responsibility of the private sector and most crucially, paved the way for human rights considerations to become a core part of the NCPs’ remit.

John Sherman, general counsel at Shift who was one of Ruggie’s key advisers from 2008–2011 and previously chaired the IBA Corporate Social Responsibility Committee, says the 2011 revision really put human rights firmly on the NCPs’ agenda. ‘The overall view was that as a result of the 2011 revision the OECD national contact points generally have become increasingly used as a forum for trying to resolve human rights-related disputes involving multinational enterprises,’ he notes. ‘This had been recognised before, but the difference is it’s now being recognised and demonstrated empirically. You’re now seeing a greater focus on human rights due diligence, which really is the centrepiece of the so-called “second pillar” of the UN framework, which the OECD guidelines adopted. NCPs are increasingly recognised as a go-to, non-judicial forum based on “soft law” principles to the extent that the Guiding Principles are “soft law”, but they can also have very hard consequences for companies that don’t want to participate.’

However, Ame Trandem, Network Coordinator for OECD Watch, says many NCPs are failing to provide effective remedies to victims of corporate abuse. ‘OECD Watch has found that less than one percent of 250 cases filed by communities, individuals and NGOs over the past 15 years have resulted in directly improved conditions for the victims of corporate abuse,’ she says. ‘More positive outcomes are needed to ensure that the OECD guidelines help deliver remedy and the first step towards achieving this is by improving the performance of the NCPs to operate in an impartial, transparent, and predictable manner, so that cases regularly lead to outcomes that are compatible with the OECD guidelines.’

Nevertheless, Kathryn Dovey, who is in charge of NCP coordination at the OECD, agrees the 2011 revision has had a profound impact on the types of cases that have been brought to the NCPs’ attention in recent years. ‘The 2011 revision was quite a significant update, both in terms of human rights having its own chapter and the alignment with the UN Guiding Principles, as well as the approach to due diligence and responsible supply chain management,’ she says. ‘The number of instances does vary from country to country but having the human rights chapter has led to an increase in cases in this area.’

According to the OECD Database more than 340 cases brought by NGOs, trade unions, business and other parties have been reviewed by NCPs across the world to date. Sherman says the stronger emphasis on human rights since 2011 has also led to a greater diversity in the types of human rights cases being filed with NCPs. ‘In the past they tended to be mostly labour-related complaints, but now there’s a wide variety of different kinds of complaints, such as indigenous rights and security-related issues, and there’s also a diversification in the different types of industries where complaints are being filed. Initially it was mostly the extractives, but now you’re seeing complaints in other industries such as manufacturing and financial services. It’s become easier for the OECD to take on these types of complaints since the revision led to this focus on human rights and human rights due diligence.’

Obstacle course

Despite this development, there are growing concerns that the guidelines’ non-prescriptive nature has led to an ever-widening gap between the best and worst-performing NCPs.

Particular scrutiny has been placed on the UK’s NCP, which, although long held up as a shining example of NCP best practice, has recently been criticised for its ineffective handling of complaints. This was strongly conveyed in a February 2016 report by Amnesty International entitled Obstacle course: How the UK’s National Contact Point handles human rights complaints under the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, which condemned inconsistencies in the NCP’s adherence to the guidelines, its inappropriately high evidential threshold for complainants, as well as questioning the partiality and structure of the NCP.

Less promising results

In 2013 the World Wildlife Fund brought a complaint to the UK NCP alleging that London-listed Soco International had breached the Guidelines over its plans to explore for oil in the Virunga National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site located in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Facilitated by the UK NCP, WWF and Soco entered into mediation. This resulted in Soco stopping its exploration activities in Virunga altogether, marking the first time that an OECD Guidelines complaint process has resulted in the total halting of a destructive project. Soco also committed to not exploring for oil in any other World Heritage Site across the world.

In 2014 civil society organisation Americans for Democracy and Human Rights in Bahrain (ADHRB) submitted a complaint to the UK NCP alleging that from 2012–2014 the Formula One Grand Prix in Bahrain led to an increase in human rights abuses in the country. The UK NCP concluded in its initial assessment that the Bahrain race had become ‘politicised, with a new risk that it may be used as a focus for actions by both opponents and agencies of the government’. Following a mediated agreement with the company, the Formula One Group made its first public commitment to respect human rights across its operations and develop a human rights due diligence policy.

Tricia Feeney, executive director of Oxford-based charity Rights and Accountability in Development (RAID), was instrumental in campaigning for widespread structural and procedural reforms at the UK NCP in 2008 after it was criticised for mishandling allegations made by the UN against British companies operating in the Democratic Republic of Congo. However, Feeney believes the UK NCP has gone downhill in the past five years. ‘Ironically since 2011 a lot of the improvements in the actual procedures that had been ushered in in the UK were mainstreamed to all NCPs and the procedural guidance that came out of that review didn’t take the UK NCP further forward, it was just catch up time for most of the others,’ she says. ‘What we feel is, having come so far and been a leader in the field, two things happened: one is the revision of the guidelines, which was heavily influenced by the Ruggie process with the UN Guiding Principles. Second, there was a complete change of team, which led to a huge loss of institutional memory with the civil servants who were operating the system. This new team came in, not having gone through the painful process of re-examining what they were doing and taking quite a lot of flak and criticism and rather basked in the acquired reputation of the previous team.’

The much delayed case with Eurasian Natural Resources Corporation in the DRC… took about three years, which is ridiculous

Tricia Feeney

Executive director

Rights and Accountability in Development

The guidelines don’t stipulate how NCPs should be structured, leading to different approaches. Some, such as those of Australia and Chile, have representatives from a single ministry. Others have representatives from more than one ministry, such as in Brazil and Germany. While Belgium, France and Sweden, have tripartite NCPs with representatives from business and trade unions in addition to government. Finland and the Czech Republic, go a step further and include NGO representation.

In this respect, the UK NCP is unique as despite sitting in the UK government’s Department for Business, Innovation and Skills and receiving funding from the Department for International Development, it has an inter-departmental steering board made up of four external members. Feeney says this level of oversight has set the UK NCP apart from the rest: ‘Although some NCPs have advisory groups, none of them have any that have the authority of the steering board, which has oversight over the UK NCP. The board members don’t get involved in specific cases but they do advise on policy issues, how to interpret things or if there are any procedural glitches, which gives them the capacity to review cases that have been concluded on procedural grounds.’

However, she recognises that increasingly the steering board hasn’t helped reduce, and in some instances has even exacerbated, delays in resolving complaints. ‘The steering board used to have a strong pool of people that could stand in as alternatives if one of their members was away or unavailable. This provided the balance that you need so that you have the confidence of all parties, but then they decided not to have them.

‘This has allowed some of the timelines to drift and there have been some inordinately lengthy delays in dealing with requests for review that have been quite unacceptable. That was the case with the Phulbari mine case in Bangladesh, where it took almost nine months to constitute the panel. We also had the much delayed case with Eurasian Natural Resources Corporation in the DRC that took about three years, which is ridiculous. This was partly because ENRC delisted and had various other problems, but this is an example where the NCP simply has to grasp the nettle and say to the company that they’ve just got to get on with it.’

Tim Cooke-Hurle, a barrister at Doughty Street Chambers in London, has represented NGOs and communities in a large number of NCP cases, including a complaint relating to oil and gas operations in Kazakhstan; a complaint against a security company by Lawyers for Palestinian Human Rights and one relating to a hike in human rights abuses in Bahrain.

The prospect of a bad decision, bad remedy or no remedy from a time-consuming process is quite high

Tim Cooke-Hurle

Barrister, Doughty Street Chambers, London

These and other cases have exposed Cooke-Hurle to the day-to-day frustrations of dealing with the NCP process. ‘There’s a distinction in human rights between being a business enterprise linked to an adverse impact on human rights and then actually causing or contributing to the human rights impact yourself,’ he says. ‘If you cause and contribute to the adverse impact on human rights then your obligation to remedy that impact is much, much stronger, but what we find is we get some really perverse decisions in relation to that standard in particular and it causes massive problems for the claimants as then you have to argue in relation to the linked by business enterprise standard, which gives far less opportunity for remedy.’

Although he is a strong advocate for the system, Cooke-Hurle says a number of underlying issues still need to be rectified. ‘It is a really good opportunity to see the whites of the eyes of the representatives of the companies and to talk to them about the problems facing the community, but because of that kind of decision-making I’ve been more reticent recently in advising people whether to go forward with these complaints because the prospect of a bad decision, bad remedy or no remedy from a time-consuming process is quite high.

‘I take quite a firm view on it: the UK has an obligation to provide access to remedy for adverse impacts on human rights that are caused by its businesses and as a result it falls to the UK and its NCP to be as robust as possible in their management of these claims and to do it efficiently, fairly and predictably.’

Ripe for reform

Many NCPs have tightened their processes and improved their operations in recent years, but Trandem of OECD Watch believes more progress is needed. ‘The NCPs who have been accepting complaints with lower evidential thresholds, provided opportunity for parties to undergo a mediation process, made efforts to carry out fact-finding, and issued final statements at the end of the process remain some of the top performing NCPs,’ she says. ‘Some of the lowest performing OECD countries are those who do not have NCP contacts in place yet and those with NCPs who have not accepted credible complaints due to lack of will or by insisting on excessively high standards of evidential proof.’

Mark Pieth, former chairman of the OECD Working Group on Bribery in International Business, agrees there are still glaring inconsistencies across the NCP system.

Less promising results

In 2013 the UK NCP received a complaint alleging that Eurasian Natural Resources Corporation had breached the general policies and human rights provisions of the Guidelines with its mining activities in the Democratic Republic of Congo. After long delays, it was concluded in February 2016 that ENRC had not met obligations under the Guidelines. The UK NCP will make a follow-up statement on the complaint in February 2017.

In 2013 the UK NCP received a request from the Lawyers for Palestinian Human Rights alleging that security company G4S was breaching the Guidelines in Israel and Palestinian Territories, particularly in relation to the company’s provision of equipment and services at Israeli prisons, detention centres, and military checkpoints. The NCP issued a statement in March 2016, finding G4S only culpable of a ‘technical breach’ in the guidelines and issued several recommendations. Following an independent review, G4S found it had done nothing wrong. The UK NCP told Global Insight that it has begun the follow-up process referred to in its final statement in March 2016 and this will be published shortly.

‘In some countries they’ve developed reports that are much more meaningful, but in others they’re very soft,’ he told Global Insight. ‘I’ve just looked at a case on trading companies of mining products where there’s an Australian report and I compared it with the Swiss report. The Australian report is straightforward and addresses issues. The Swiss report faffs around. In essence though, for both reports the challenge is what you make of it. Even if you are straightforward, what are the consequences and I think here the OECD could learn from other groups that this body is hosting. I’m thinking of tax, corruption and money-laundering, where they’re much more to the point and much tougher.

‘Everybody seems to be protecting the major companies that they are hosting. So there are big sensitivities and speaking about Switzerland, it’s a huge hub of multinational corporations, quite disproportionate to the size of the country, and of course Switzerland has an interest in keeping those companies in the country, in keeping them happy and so these reports turn out to be far more diplomatic than other reports.’

Kirstine Drew, a senior policy adviser at the Trade Union Advisory Committee (TUAC) to the OECD, believes it boils down to individual governments to ensure their NCPs are effective as possible. ‘Fundamentally I would say it’s about political will because if governments want the NCPs to work then they can make them work,’ she says.

‘Some of them don’t have any resources and if you don’t have any resources, there’s not much you can do. For others it’s structure. Although we would prefer that an NCP is not located in a government’s department of investment – as that can raise a conflict of interest – the key thing is if they’ve taken steps to address any of these potential conflicts, that they’re resourced and they’ve got staff with the proper capacity. If they’re really interested in investment and they have no knowledge or interest in human rights, workers’ rights or trade union rights, the wrong people will end up doing the job.’

Drew says Canada’s moves to impose sanctions on China Gold International Resources for failing to engage in the NCP process (see box, Beyond the call of duty) is an example that other NCPs should follow. ‘That’s what we want to see all the NCPs doing. If you think about legal systems, they bring in mediation as an option but the reason they go to mediation is because they don’t want to be prosecuted. It’s about having that background threat of something else – the NCPs don’t have that.

‘You have some reputational damage because the NCPs have to produce a final statement and so now if the company is invited to come to the table but doesn’t come then this would be on the record. If investors take this into account then governments should too and that’s what the Canadian policy is doing and there’s absolutely no reason why every single NCP can’t do that. This is a clear step to take to improve the NCPs and it’s in the hands of government to take it.’

The OECD is playing its part though, notes Dovey and Nieuwenkamp. The Working Party on Responsible Business Conduct adopted an action plan on NCPs in late 2015. ‘We’ve carried out peer-learning reviews between the more sophisticated NCPs and there have also been lots of capacity-building initiatives for new or less experienced NCPs,’ says Nieuwenkamp.

The OECD could learn from other groups… tax, corruption and money-laundering, where they’re much more to the point and much tougher

Mark Pieth

Former chairman of the OECD Working Group on Bribery in International Business

As just one example of a successful peer-learning exercise the UK NCP recently hosted a sector-based workshop in London in partnership with the Institute for Human Rights and Business. The event focused on NCPs and the construction sector and was attended by the Swiss NCP. Dovey says such initiatives have been extremely helpful:

‘The NCPs are able to share cases that have gone before them and give examples of where the guidelines are better promoted. Amongst the 46 countries there are certain NCPs, such as the UK, US, Netherlands, Germany and Brazil, which have received a lot of cases. What we’re seeing in peer-learning is they are able to share these experiences and share characteristics, whether that be in relation to their structure or the types of cases they’ve received.’

In June 2015 the OECD Ministerial Council Meeting and the G7 Summit recognised the NCPs’ important role in providing access to remedy. As Nieuwenkamp says, ‘this is the best political the NCPs have ever had’.

That said, many agree the NCP system is due another shake-up. ‘NCPs are such a unique opportunity in the business and human rights infrastructure,’ says Cooke-Hurle. ‘There are cost implications of course, but actually it’s a remarkably efficient procedure with very few people working for it and it’s enabling a forum to resolve very, very serious disputes. If we’re going to let our multinationals run rampant then we’ve got to provide that opportunity and we’ve agreed under law that we will.’

Trandem says procedural reform, political will and resources will be key to securing the legacy of both the OECD guidelines and the NCP system: ‘In the end, the value of the OECD guidelines will not be judged by their age, but rather by the importance governments give them, the way in which they handle the implementation procedures and whether they serve as a model in ensuring corporate accountability and access to remedy.’

Ruth Green is Multimedia Journalist at the IBA and can be contacted at ruth.green@int-bar.org