Digital transformation and human rights

Jennifer Venis, IBA Content EditorMonday 10 February 2020

As governments around the world increasingly move to automate social security, Global Insight evaluates the dangers that unchecked digital transformation pose to the rights of the world’s poorest citizens.

A digital transformation of governance is taking hold of the world. While this may have some benefits, the rate of change and lack of industry regulation raises human rights concerns. Welfare states have been swept up in the wave of transformation, with digital surveillance, automated sanctions and predictive algorithms serving a variety of functions previously handled by human decision-makers.

In a 2019 report about the rise of ‘digital welfare states’, Professor Philip Alston, United Nations Special Rapporteur for extreme poverty and human rights, argued ‘systems of social protection and assistance are increasingly driven by data and technologies that are used... to automate, predict, identify, surveil, detect, target and punish’ the poor. In the race to digitalise, careful consideration of the effect on the rights of the poor may have fallen by the wayside.

Digitalisation raises concerns including privacy violations, targeted surveillance, discrimination in eligibility and fraud assessments, and a lack of transparency regarding how decisions are made or can be challenged. Ultimately, the result is the denial of services, with potentially severe consequences.

Digital ID but nothing to eat

India’s system of biometric identification, called Aadhaar, was endorsed by the World Bank and ruled to be a legitimate tool in the delivery of social welfare by the Indian Supreme Court, despite privacy concerns. Introduced in 2009, Aadhaar holds the data of 1.2 billion people, all of whom have been issued a 12-digit unique identifying number in exchange for personal information, a photograph, and iris and fingerprint scans.

Varun Mansinghka, Asia Pacific Regional Forum Liaison Officer of the IBA Poverty and Social Development Committee, highlights ‘failures of the matching system and potentially dire consequences’. He tells Global Insight that ‘reports of individuals being denied food rations, resulting in starvation, are not uncommon and are occasioned by: either the individual not obtaining an Aadhaar number; or the biometric recognition system at the government ration shop failing to match the fingerprint of the individual with the record in the Aadhaar database’.

In ration shops in rural communities, vendors can face difficulties in acquiring signal and connecting to Aadhaar. Their machine may be able to scan fingerprints but not irises, or fail to work for farm labourers whose fingerprints are no longer readable. There is supposed to be an analogue system, but this option has not been communicated to all ration vendors. Activists say that in one state – Jharkhand – at least 14 people have died of starvation following the replacement of handwritten ration cards with Aadhaar.

Reports of individuals being denied food rations, resulting in starvation, are not uncommon

Varun Mansinghka

Asia Pacific Regional Forum Liaison Officer, IBA Poverty and Social Development Committee

Some people have found their pensions paid into someone else’s account, while others have been falsely recorded as dead. Mansinghka says ‘a grievance redressal mechanism is provided’, but it is largely an online system. ‘The majority of the individuals targeted by the government’s welfare schemes are likely to be affected by illiteracy and poverty’ and therefore may be unable to access it. An understanding of the experience of India’s poor seems lacking in Aadhaar’s design.

People on the receiving end of digital welfare systems are rarely involved in their development. Developers are left ill-informed and unable to foresee problems. Professor Alston’s 2019 report highlights this, calling for intended users to be involved in the design and evaluation stages of such systems. The report says ‘programs that aim to digitize welfare arrangements should be accompanied by programs designed to promote and teach the needed digital skills and to ensure reasonable access to the necessary equipment, as well as effective online access’.

The technology behind digital welfare states is generally created by large multinational companies. In the United Kingdom, for example, the Department for Work and Pensions contracted companies including IBM and Accenture.

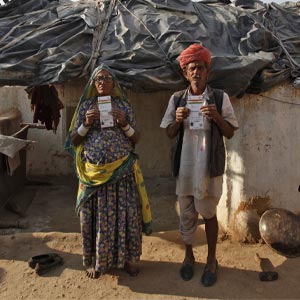

Ghewar Ram (55) and his wife, Champa Devi (54), display their Unique Identification (UID) cards outside their hut in Merta district. REUTERS/Mansi Thapliyal

Hannah Wiggins, Client Delivery Executive at government procurement consultants Advice Cloud, tells Global Insight that ‘technology companies intending to sell their offerings to the public sector must adhere to particular regulations that aim to make such offerings “accessible”.’ UK-based Advice Cloud hasn’t created digital welfare systems but does promote them, and works ‘with a number of private sector clients who sell their technologies and digital services to government’. Wiggins highlights the UK government’s Technology Code of Practice, which tells companies to: ‘Develop knowledge of your users and what that means for your technology project or programme.’

Chris Holder, Co-Chair of the IBA Technology Law Committee and a partner at Bristows, believes failing to understand users leads to data inaccuracies, and hindered access. ‘If you’re going to create a policy meant to cover people below the poverty line, you have to have reliable, accurate data on how they live. And if these people don’t interact with the digital world, their data is not going to make it into the relevant data set,’ he says.

Not all are equal before the machine

In its April 2019 Ethics guidelines for trustworthy AI, the European Commission highlighted the importance of human involvement in digitised systems, promoting human intervention in every decision cycle and during the design, as well as providing human ‘capability to oversee the overall activity’.

In France, the draft bioethics bill enshrines this human-centric approach in the use of advanced healthcare technology. To keep doctors looped in, the ‘human warranty in the use of artificial intelligence’ (Article 11 of the draft bill) is based on the ‘concept that we do not want doctors entrusting their role to machines,’ explains Cécile Théard-Jallu, a partner at De Gaulle Fleurance & Associates in Paris specialising in technological innovation and digital strategy.

‘We need them to stay in control and we need patients to be made aware of the parameters of use and purpose of the technology,’ Théard-Jallu says. ‘The trustability of the artificial intelligence (AI) based decision-making process must be confirmed by a series of measures including establishing targeted, prescheduled or random verification procedures for anticipating, managing and mastering functionalities of AI tools and their biases, which would be run by internal and external supervisory bodies throughout the R&D and healthcare cycle.’

In digital welfare states, however, there can be a lack of human oversight. In Austria, an algorithm that categorises people into one of three groups determines the assessment of a person’s entitlement to social support. The first group, who should have relative ease finding employment, and the third, who have few job prospects, receive little support. Only the middle group have access to adequate social security, according to digital rights non-governmental organisation epicenter.works. The organisation says the system explicitly deducts ‘points’ from claimants who are older, from non-European Union countries or have health problems.

The algorithm’s insights are intended to be advisory, with human decision-makers retaining oversight. But epicenter.works suggests the instances of job centre staff overruling decisions will decrease over time because the algorithm reduces the need for complex consideration by counsellors. The NGO is concerned the algorithm will be viewed as an objective system and staff may fear having to justify their decisions. In this way, epicenter.works argues, implemented bias – which currently means women with children are getting fewer points than men with children, for example – ‘will seldom be corrected’.

Professor Emeritus Neil Gold, Co-Chair of the IBA Poverty and Social Development Committee, laments the lack of human involvement in many digital welfare states: ‘the individual need not and cannot be seen and so the faceless system neither sees nor expresses concern or compassion about the circumstances of the poor’.

Technology companies intending to sell their offerings to the public sector must adhere to particular regulations that aim to make such offerings “accessible”

Hannah Wiggins

Client Delivery Executive, Advice Cloud

Risk calculation tools are also used elsewhere. The Michigan Unemployment Insurance Agency (UIA) launched the Michigan Integrated Data Automated System (MiDAS) in 2013 to eliminate benefit fraud among the unemployed. Fraud penalties were initially high at 400 per cent on the claimed amount of fraud, although the UIA informs Global Insight that legislation passed in 2018 reduced penalties to 100 per cent on the first offence and 150 per cent on subsequent offences.

The UIA did not respond when asked about an incident that led to automatically generated notices with incriminating questionnaires being sent to individuals marked as suspicious by the algorithm, which allegedly used corrupted data. Around 34,000 people were wrongfully accused of benefit fraud in 2013–2015.

In the Netherlands, a case at the District Court of The Hague is focused on the targeting of a digital system. The risk calculation tool System Risk Indication (SyRI) uses data collected by various government agencies to predict the likelihood of an individual engaging in violations of labour laws and benefit, or tax fraud. The lawsuit argues that the system’s selective rollout in low-income neighbourhoods unfairly targets the poor for increased scrutiny.

In digital welfare states, the focus on fraud prevention and need categorisation suggests that benefit recipients are not intrinsically entitled to support. This and such targeted scrutiny positions them as applicants, not rightsholders, with some less deserving of support.

If a benefit recipient is seen as an applicant, there will be criteria to meet and conditions to fulfil. Both Australia’s Targeted Compliance Framework (TCF), implemented in 2018, and the UK’s Universal Credit use sanctions to enforce compliance with the conditions of benefit provision. In a May 2019 submission to the UN report on poverty, the Human Rights Law Centre (HRLC) accused successive Australian governments of targeting benefit recipients for cost-saving measures, demonising many as ‘undeserving of support or political inclusion’.

Individuals on TCF – described by the HRLC as ‘a highly automated system of sanctions’ – are bound by mandatory participation requirements, including job application quotas. A failure to meet and record completion of any of these requirements amounts to a ‘mutual obligation failure’. The HRLC says ‘[p]ayment suspensions are automatically triggered by a person receiving a demerit point… without any consideration of the hardship this might cause’.

A spokesperson for the Australian Minister for Employment, Skills, Small and Family Business disputes the punitive nature of TCF. They explain that for ‘the majority of job seekers who miss a requirement, incentive to re-engage with requirements is provided by temporary payment suspension – which is back-paid upon re-engagement. A “demerit” is only accrued if they are assessed as having no valid reason for their non-compliance.’

Lack of transparency

When individuals cannot understand why a decision has been made about entitlement or a penalty, they may struggle to seek redress or to access their rights. The inaccessibility of such information stems from a range of causes, including governments’ emphasis on protecting automated processes from abuse by fraudsters.

In its July 2019 report Computer Says ‘No!’, the UK charity Child Poverty Action Group (CPAG) highlights the legal rights of benefit claimants to understand the reasoning behind decisions that may have harmed them. Yet, the charity cites cases where Universal Credit claimants experience barriers in seeking such information.

Universal Credit is the UK’s digital-by-default benefit system, which was fully implemented by 2018. A UK Department for Work and Pensions spokesperson tells Global Insight that ‘automation means we are improving accuracy, speeding up our service and freeing up colleagues’ time so they can support the people who need it most’.

However, CPAG reports that Universal Credit helpline staff are often unable to explain how a claimant’s award has been determined because they don’t have access to payment calculations – which, in the vast majority of cases, are processed automatically on Universal Credit’s digital system.

The Rt Hon Sir Stephen Sedley, the former Lord Justice of Appeal, says in the Foreword to the CPAG report that ‘The rule of law means… that everyone must know, or be able to find out, the rules and laws by which their lives are regulated; and secondly, that everyone is entitled to challenge, whether by internal review mechanisms, by appeal or by judicial review, the lawfulness of their treatment.’

Excessive surveillance of welfare claimants can violate their right to private life under Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights

Professor Virginia Mantouvalou

Professor of Human Rights and Labour Law, University College London

In this way, people on the receiving end of digital welfare states could be denied access to rights that should be protected by the rule of law. Professor Alston argues in his report that a lack of transparency makes governments less accountable to their citizens and the public must ‘be able to understand and evaluate the policies that are buried deep within the algorithms’.

Regardless of how or why a decision is made in any digital welfare state, humans must remain responsible for the outcomes, says Holder. He highlights an accountability issue in the language used by regulators: ‘In the EU General Data Protection Regulation, there is provision for individuals to challenge decisions made by machines. But machines don’t make decisions. They analyse data sets and generate insights. That insight is then used by human beings to make a decision,’ he says. ‘You can’t abdicate responsibility for human decision-making via a machine.’

Rights by design

As far back as 2013, the European Commission was pushing for technology companies to take some responsibility for the outcomes of their products. In its ICT Sector Guide on Implementing the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, the Commission argued it is ‘critical to embed human rights from the earliest design phases’.

Holder says ‘there’s a lot of talk about AI companies having ethical directors looking at these issues to make sure that there is an ethics-by-design type of approach when it comes to the use of algorithms. People who are running or creating these products must have ethics at the forefront of their minds, but the data sets used must be reflective of society as a whole and not just one area.’

Only some of the codes of ethics technology companies produce refer to human rights standards. Professor Alston’s report argues that these references are self-serving and not grounded in legal outcomes. The codes also lack accountability mechanisms.

Professor Aneel Karnani, Professor of Strategy at the Michigan Ross School of Business, has written extensively about the roles of the state, the private sector and civil society in poverty reduction. He says ‘we must be careful that digital welfare systems are not built in a way that makes them vulnerable to abuse, because while one government might respect human rights, the next may not’.

‘A company is not a moral organisation, it’s primarily an economic organisation,’ adds Professor Karnani. ‘If it can respect human rights without losing profits, then it will do it, but the chances of a company standing up to a government and refusing to create a discriminatory system is small because the government can find another company to do it.’

Holder, meanwhile, believes technology companies won’t knowingly create a product that violates rights, but highlights an inability to foresee all possible outcomes. He says, ‘Big tech… have a duty of care to produce IT systems that governments ask for, for example, and not to tread over an ethical line if they’re being asked to do so. But they produce a whole range of things that individuals use for their own purposes. Who knew, for example, the change that was going to be created by the internet?’

International duty of care

Karnani believes the real danger is that some governments do not recognise their duty of care, as they’re either unwilling to protect human rights or intent on violating them.

Holder argues that the rule of law in such countries needs to be enforceable so governments cannot misuse surveillance or other technology.

Until 2019, Poland used a system designed to algorithmically determine entitlement based on data analysis that categorised benefit applicants. In late 2018, Poland’s Constitutional Court ruled that the scope of data used for profiling should have been part of a legal act overseen by Parliament and not solely determined by the government. After this ruling, and amid pressure from the Human Rights Commissioner and civil society, the government abolished the algorithmic scoring system.

Professor Karnani emphasises the role of civil society and international governments or bodies, who he says must be able to hold governments to account. But many of the international bodies producing guidance on the ethical use of technology don’t have the power to enforce them. Théard-Jallu points out that the April 2019 EU guidelines on ethics and AI are soft law and have no binding force.

A homeless person sleeps under a blanket on the porch of a shuttered public school in Detroit, Michigan 23 July 2013. REUTERS/Rebecca Cook

Professor Virginia Mantouvalou, Professor of Human Rights and Labour Law at University College London, believes legal frameworks are in place in the form of international human rights law standards. At her inaugural lecture entitled ‘Structural Injustice and Workers’ Rights’, to be published in the journal Current Legal Problems, Professor Mantouvalou argued that ‘excessive surveillance of welfare claimants can violate their right to private life under Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) because it may be viewed as disproportionate to the aim pursued by the authorities’.

She also says ‘there is empirical evidence from European countries that welfare schemes with strict conditionality are “a driver of in-work poverty”’ and conditions ‘requiring applicants to accept exploitative jobs… may give rise to issues under Article 4 of the ECHR (prohibition of slavery, servitude, forced and compulsory labour).’

The Canadian and French governments have looked to secure international agreement on AI and ethics. In May 2019, both states launched a draft declaration for a new International Panel on Artificial Intelligence, which contained a pledge to support development of AI that would be ‘grounded in human rights, inclusion, diversity and innovation’. The declaration would require participating states to commit to a ‘human-centric and ethical approach to AI’ that is grounded in respect for human rights, institutions of democracy, access to information and the rule of law.

Technology companies that Global Insight spoke to were also keen to highlight the potential positive applications of technology in the public sector. Accenture highlighted a social care project with the charity Age UK, in which Accenture piloted an AI-based program that, according to a press release, ‘runs on the Amazon Web Services (AWS) cloud [and] can learn user behaviors and preferences and suggest activities to support the overall physical and mental health of individuals ages 70 and older’.

However, technology use in the public sector is likely to prompt questions about data access, including by governments with potentially malicious intentions. Ensuring the safe use of technology involves many parties, from human decision-makers working with algorithmic processes, to technology companies designing the software, to governments and international bodies regulating its use.

Universally acknowledged human rights standards must be factored in at every stage in the process of digitisation, but without international enforcement of those standards, digital welfare states will remain vulnerable to abuse, with the world’s poorest bearing the consequences.

Jennifer Sadler-Venis is Content Editor at the IBA and can be contacted at jennifer.sadler-venis@int-bar.org