Competition implications of the transition to 5G

Dr Will Taylor and Adrien Cervera-Jackson[1]

Introduction

5G is the next generation of mobile technology. While it promises a step-change increase in performance and functionality compared to 4G and is expected to give rise to a number of new use cases, it also requires significant investment from mobile network operators (MNOs).

However, the business case for 5G investment is unclear. The need for new capital expenditure arrives at a time when MNO revenues and average revenue per user (ARPU) have been flat or declining for several years, while connections and data usage by consumers have been increasing. This is putting pressure on current MNO business models. New use cases that would enable MNOs to monetise 5G are on the horizon, but it is unclear when they will arrive and provide new revenue streams. At this stage, it is also unclear whether the current Covid-19 pandemic will exacerbate these challenges.

These trends are putting pressure on MNOs to combine (merge) or collaborate (share network infrastructure) in order to achieve investment efficiencies, both of which may raise competition concerns. Both mergers and network sharing agreements (NSAs) have the potential to benefit consumers through increased investment but may also reduce competitive tension between MNOs.

Recent mergers between small MNOs have raised issues about the level of investment that would occur by the parties in the absence of the merger and the ability of the newly created firm to compete against the larger and better-resourced first and second players in each market. This was a key consideration of the courts in both the Vodafone Hutchison Australia (VHA)/TPG Telecom (TPG) (Australia) and Sprint/T-Mobile (United States) cases.

A frequently occurring consideration is whether alternative arrangements, such as infrastructure sharing, could allow MNOs to achieve similar efficiencies to a merger, but with less harmful effects on competition. NSAs generally benefit consumers in terms of faster rollout, cost savings and improved coverage but they may have a negative impact on competition in some circumstances.

From a competition perspective, infrastructure sharing has traditionally been viewed as more benign than a merger, particularly when it involves the sharing of passive, rather than active, infrastructure.[2] However, recent NSAs have involved more active sharing, which has heightened regulatory scrutiny of those arrangements given the greater risk that active sharing could reduce competition between MNOs – for example, the ongoing European Commission investigation into the NSA between O2 CZ/CETIN and T-Mobile CZ (Czech Republic).

Some mergers can also affect infrastructure sharing. In the proposed H3G/O2 transaction (UK), the Commission and the European General Court (‘General Court’) assessed the merger’s impact on investment by examining its effects on two existing NSAs involving the merging parties.

Mergers and NSAs between MNOs have the potential to benefit consumers through increased investment and the dynamic competition benefits they bring. This increased investment occurs when mergers or NSAs relieve capital constraints and/or lower the per unit cost of expanding the network (due to network or spectrum synergies). In the latter case, this makes investments that are not profitable on a standalone basis profitable.

However, mergers and NSAs may also reduce competitive tension, particularly in a more static sense. The overall effect on investment and consumer welfare (ie, prices and quality) will depend on the specific facts and circumstances of each case. The cases discussed below highlight that for both mergers and NSAs, whether there is a positive impact on investment depends on various factors. With respect to NSAs, the competitive effects also depend on the nature of the sharing (active versus passive), the area covered by the shared network (urban versus rural) and the ownership structure of the network sharing (joint venture versus geo-split agreement).[3]

Economic analysis and evidence have an important role to play in evaluating the trade-off between efficiency gains and anti-competitive effects arising from consolidation and cooperation between MNOs and assessing the overall impact on investment and competition, as demonstrated in the General Court’s recent H3G/O2 judgment.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. Section 2 explains the basics of mobile network economics and the properties of different spectrum bands, then describes the difference in performance between 5G and 4G. Section 3 sets out the challenges to MNO business models associated with 5G investment, which requires significant capital expenditure at a time when MNO revenues and ARPU have been flat or declining for several years. Section 4 describes the resulting rationale for MNOs to merge or collaborate to achieve investment efficiencies, sets out the trade-off between the potential efficiency gains and anti-competitive effects associated with mergers and NSAs, and discusses recent cases where these issues have been examined around the world. Section 5 concludes on the implications for investment of MNOs merging or collaborating.

What is 5G and how is it different from 4G?

To understand what 5G is, how it differs from 4G and why rolling it out involves large investment from operators requires an appreciation of the economics of mobile network capacity and some fundamentals on the capacity and coverage properties of different spectrum frequency bands.

Beginning with mobile network economics, MNOs have three primary means of increasing the capacity and performance of their network:

1. More sites:for a given demand for traffic by customers, increasing the number of ‘base stations’ decreases the number of customers using a given base station, thus reducing congestion at that base station.[4] To use a traffic analogy, building more cell towers is similar to building additional roads of the same size to enable more traffic to flow.

2. More spectrum: for a given base station and technology, the amount of traffic that can be carried is limited by the available spectrum. Therefore, increasing the amount of spectrum available to the MNO increases the capacity of a given base station. Continuing the traffic analogy, more spectrum is similar to widening an existing highway to add extra lanes.

3. Increased spectral efficiency:increased spectral efficiency refers to equipment being able to use a given amount of spectrum more efficiently by using another, higher performance modulation technology. Using the traffic analogy, a straight and flat road can carry more traffic at a higher speed than a winding road that travels over hills.

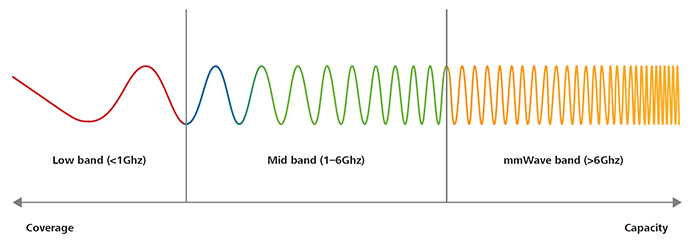

Regarding spectrum, different spectrum bands have different uses, which are broadly determined by the amount of spectrum available in a band (which determines the capacity available in a band) and its ‘propagation’ characteristics (ie, how far it can travel and the extent a signal is easily blocked by trees, walls, etc). Figure 1 illustrates the broad categorisation of spectrum bands and the purpose they serve.

Figure 1: Spectrum 101: different horses for different courses

Broadly, low-band spectrum (<1Ghz) is typically used for coverage, as the broad wavelengths can travel long distances and are not easily obstructed by walls, trees or other natural features. Because of its long reach, each base station in low band can cover a larger surface than other bands, and thus fewer base stations (and investment) are required to reach a given service coverage. However, in a low frequency band there is not a large amount of spectrum available. For example, in the 700MHz band, there is only 100MHz of spectrum available, which is not a lot of capacity spread among operators. In Australia, Optus recently noted that there is only 130MHz of sub 1-GHz spectrum licensed for use in mobile services.[5]

By contrast, mmWave spectrum, which has a very narrow wavelength, has a far greater amount of spectrum available in a given band. For example, Verizon in the US acquired more than 1GHz of spectrum in the 39GHz band and holds 1.7GHz across three mmWave bands.[6] However, very high frequency spectrum does not propagate as well as low frequency spectrum, in that it is more likely to be obstructed by natural features of the environment (trees, buildings, hills, etc) and is less able to penetrate walls and windows. Therefore, it provides good capacity but poor coverage. As such, mmWave frequency is being touted as most useful for dense urban deployments.

In between these two extremes, ‘mid-band’ spectrum provides a balance of both coverage and capacity. As a result of these different characteristics and constraints on spectrum availability, the GSM Association (GSMA – originally Groupe Spécial Mobile) is recommending that regulators aim to make available 80–100MHz of spectrum per operator in 5G mid-bands (eg, the 3.5GHz band) and 1GHz per operator in mmWave bands.[7] The GSMA has also noted that there is a need to identify more spectrum below 1GHz so that rural areas (which are not densely populated and therefore are best economically served using low-band spectrum) benefit from 5G.[8]

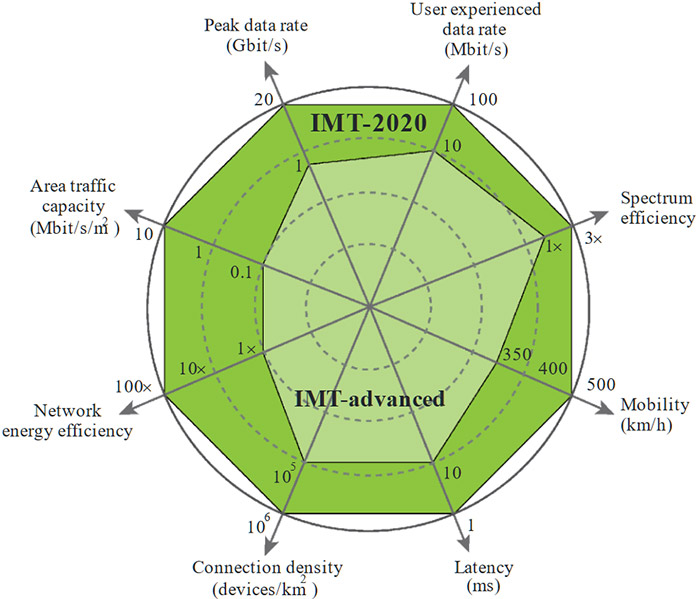

5G differs from 4G in that it will increase the spectral efficiency of existing spectrum bands used to provide mobile services, but it will also use mmWave bands, which have not previously been used to provide mobile services. In pure technical performance terms, 5G is a step change compared to 4G (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Technical performance of 5G (IMT-2020) versus 4G (IMT-Advanced)

Source: ‘Recommendation ITU-R M2083-0’ (International Telecommunications Union 2015).

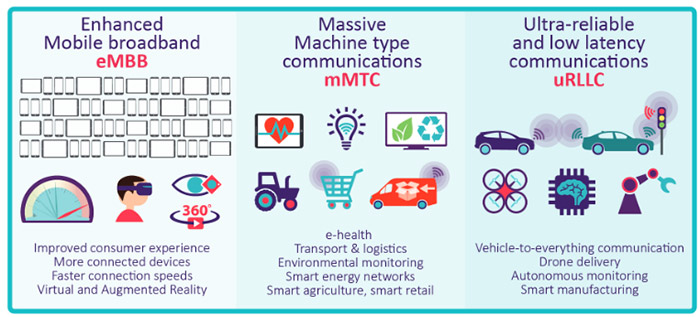

This raw technical performance is slated to do more than merely reduce buffering times or increase video-streaming resolution on consumers’ phones. Reduced latency (the response time for two devices to communicate with each other), power efficiency and mobility are expected to give rise to various new use cases such as ‘internet of things’ (IoT) applications, driverless cars and telemedicine. By improving the capacity and speed of mobile networks, 5G may also make fixed wireless access a substitute for fixed broadband networks for some consumers.[9] Figure 3 from Ofcom (the UK telecommunications regulator) summarises some expected use cases for 5G.

Figure 3: 5G use cases

Source: ‘Update on 5G spectrum in the UK’ (Ofcom 2017).

5G will cost a lot, and the MNO business case isn’t clear

While 5G promises much for consumers and the economy more generally, it is also likely to require significant capital expenditure from MNOs, over and above the normal costs that operators incur in upgrading equipment. Two key reasons for this include:[10]

1. the key spectrum bands for 5G (the ‘C-band’ and mmWave spectrum) are not currently owned or used by MNOs;[11] and

2. a much denser network of base stations is likely to be required to deliver true 5G speeds, due to the poor propagation characteristics of mmWave spectrum.[12]

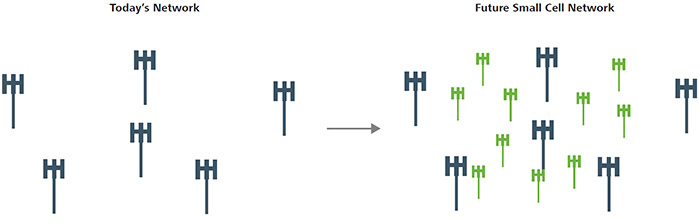

The second point is illustrated in Figure 4, which shows stylistically how the topology of networks might change as mmWave spectrum is deployed.

Figure 4: Change in network topology from rolling out 5G mmWave technology

Therefore, operators will need to construct and operate a network with many more base stations than they presently operate. McKinsey estimates that the additional total cost of ownership (ie, opex and capex) could peak at between 60 per cent and 300 per cent of current spend, depending on data growth rates.[13] Clearly, the additional costs of 5G are substantial.

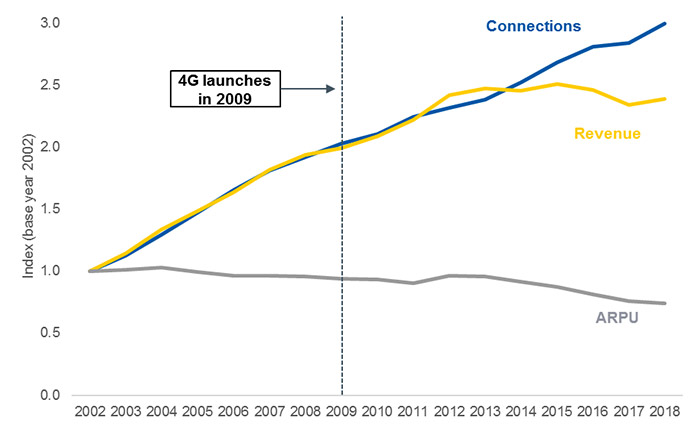

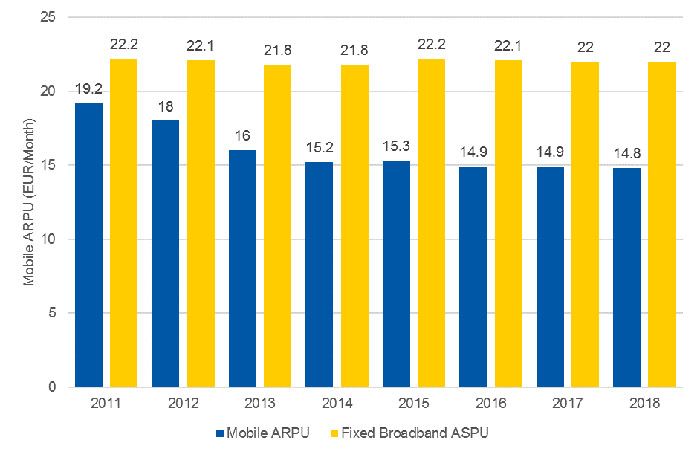

While operators are expected to incur large costs in rolling out a 5G network in the future, revenue and ARPU have been flat or falling in recent years. Figure 5 plots indexes for the number of connections, ARPU and revenue for wireless carriers in the US. Interestingly, mobile connections and revenue were closely correlated until around 2011, after which connections have continued to grow but mobile revenue has remained relatively flat. As a result, ARPU has been declining over the same period. A similar pattern holds for Europe, as demonstrated by Figure 6, which shows a similar fall in mobile ARPU since 2011, while fixed broadband ARPU has remained relatively stable.

Figure 5: Mobile revenue has been relatively flat in the US, while mobile ARPU has been falling since 2012

Source: ‘Topline results of the 2018 Cellular Telecommunications and Internet Association Wireless Industry Survey’ (CTIA 2019).

Figure 6: Mobile ARPU has been falling in Europe, while fixed ARPU has remained stable

Source: ‘The State of Digital Communications 2019’ (ETNO Annual Economic Report 2019).

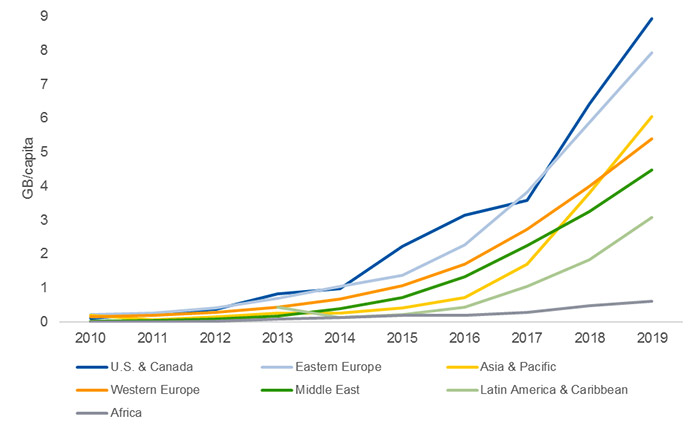

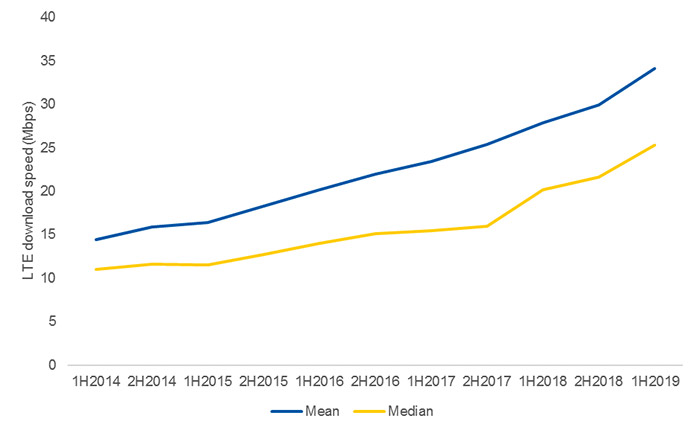

Falling ARPU, which likely reflects lower-quality adjusted prices, is not necessarily a bad thing from a societal perspective.[14] To the extent that competition is driving lower prices and higher-quality products, it is, in fact, a good thing. The exponential increases in data consumption, in conjunction with increased speeds as new technologies are rolled out (see Figures 7 and 8), suggests that consumers are benefiting greatly. Falling ARPU could also be the result of a change in connection mix. For example, an increase in low-revenue IoT and machine-to-machine connections could materialise as both a decrease in ARPU and an increase in total revenue since it represents a new revenue stream.

Figure 7: Average monthly mobile data traffic (GB per month per capita)

Source: Authors’ analysis of Telegeography’s GlobalComms database.

Figure 8: Mean and median total long-term evolution (LTE) download speeds in the US

Source: ‘Communications Marketplace Report 2018: 20 February 2020 data update’ (FCC 2020).

However, falling ARPU could also reflect that consumer willingness to pay for ever-increasing mobile speeds and capacity provided by new generations of technology has reached a ceiling. The increased expenditure requirement at a time when revenue is falling or flat is, therefore, putting pressure on existing MNO business models.

Of course, historic falling revenue is not a problem if consumers are willing to pay more for 5G, either by existing mobile users paying a premium or through developing new use cases that create new revenue streams. At this stage, it is unclear whether MNOs will be able to charge a material premium for 5G. For example, a number of operators are not charging a premium for 5G[15] and a 2018 survey found that fewer than one-third of Americans would be willing to pay a premium for 5G.[16] Of course, MNOs do not need to charge an explicit premium for 5G if they can achieve the same outcome by selling higher data allowance packages that are 5G-only (in effect, bundling 5G and large data caps) at a higher price. To the extent market practice moves towards plans with no data caps, this would be a difficult pricing strategy to implement.[17] However, more recent surveys by equipment vendors have found that consumers would be willing to pay a premium for 5G.[18] As previously noted, 5G promises new use cases, which should result in new revenue streams for operators, but it is not clear when these new use cases will arrive.

The impact of the current Covid-19 pandemic on MNOs is unclear. While fixed-line traffic appears to have increased dramatically as people spend more time at home,[19]

this could result in a reduction in mobile traffic as consumers spend more time connected to Wi-Fi.[20] However, while some operators are reporting declines in mobile traffic during the pandemic,[21] others are reporting increases.[22] Declines in mobile traffic may reduce the pressure on an operator to upgrade to 5G from a network capacity perspective. A recession may also place financial strain on operators, as some customers disconnect or downgrade their plans as a result of financial hardship.[23] However, if mobile traffic does increase, 5G may be a more cost-effective way of expanding network capacity. Therefore, the Covid-19 pandemic may exacerbate some of the pressures described earlier in this section, though the impact is presently unclear.

As a result, MNOs are combining and collaborating, with competition implications

The previous section describes the financial pressures MNOs are facing as a result of flat revenues, falling ARPU, increased consumer data demand and the impending investment required for 5G. As a result of these pressures, four broad trends are observed:

1. European MNOs have been spinning off their tower businesses to third parties to free up cash;[24]

2. open access/third-party neutral carriers have entered the market and begun to sell network capacity to MNOs;[25]

3. smaller MNOs have been merging and combining with larger rivals, including two recently litigated four-to-three mergers in the US and Australia and the ‘four-to-three wave’ that hit Europe in 2012 (ie, cleared acquisitions in Austria, Germany, Ireland, Italy and the Netherlands; a blocked transaction under appeal in the UK; and an abandoned deal in Denmark);[26] and

4. MNO infrastructure sharing, which traditionally involved only passive infrastructure, is moving up the value chain into active infrastructure.

The first two trends are expected to be largely pro-competitive and, therefore, aren’t the focus of this article.[27] The remainder of this article considers the impact on investment of the latter two trends: MNOs merging and sharing infrastructure.[28] The prospect of gaining a first mover advantage may give some MNOs incentives independently to invest in 5G infrastructure (eg, Everything Everywhere launched the UK’s first 5G service in six cities in May 2019). However, the scale of the investment required and the uncertainty associated with consumer willingness to pay for 5G mean the incentives might not be the same for all MNOs. There may be a benefit for some MNOs to wait for this demand uncertainty to be resolved (ie, a second mover advantage) by observing how successful the initial investment is before investing themselves, either independently or jointly with other MNOs.

The impact of two recent four-to-three mergers on 5G investment

Beginning with mergers, 5G network investment was at the heart of two recently litigated four-to-three mergers:

1. Sprint/T-Mobile: T-Mobile and Sprint were the third and fourth players respectively in the US mobile market. Following a settlement with the Department of Justice on 26 July 2019, subject to divestment undertakings, the merger was unsuccessfully challenged by state Attorneys General in the Southern District Court of New York;[29]

2. VHA/TPG:VHA andTPG were the third and fourth players respectively in the Australian mobile market. In the fixed market, TPG was the third player and VHA was the fourth. Following a statement on 8 May 2019 that the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) intended to oppose the merger,[30] VHA sought a court declaration that the proposed acquisition would not substantially lessen competition. The court found in VHA’s favour on 13 February 2020.[31]

In both of these transactions, a key analytical question pertained to the level of investment that would be made by the parties in the absence of the merger and the ability of the newly created firm to compete against the larger and better-resourced first and second players in each market. In both situations, it was argued that the proposed merger between the third and fourth player would create a stronger third player that would provide a greater competitive constraint than the two firms would be able to provide separately.[32] This argument ultimately prevailed in both cases, though not without contentious litigation and, in the case of Sprint/T-Mobile, an undertaking to set up Dish as a fourth player.

There are a number of conceptual reasons why a merger might lead to increased investment, which are set out below, along with commentary from the VHA/TPG and Sprint/T-Mobile judgments:

Increased scale and scope improve the business case for investment in common/shared network assets

Many investments in telecommunications networks are lumpy and fixed costs are high. Combining two mobile networks or a fixed and a mobile network (as was the case with VHA/TPG) improves the business case for investment in shared infrastructure, since the same costs are spread over more customers. The VHA/TPG decision states that ‘MergeCo will benefit financially from achieving scale. Scale is important for MNOs, as it enables the fixed costs of providing coverage to be recovered across a larger number of customers’.[33] Related to these cost savings, the decision states, ‘Further, I do not consider that MergeCo would use its net profit after tax to pay dividends to its shareholders or to pay down debt, at the expense of using its financial firepower to invest in its network or compete for market share’.[34]

Relieving capital constraints

In both VHA/TPG and Sprint/T-Mobile, a key issue was the ability of one of the players to finance investment absent the merger. In VHA/TPG, the evidence suggested that VHA was facing financial difficulties that wouldn’t be resolved absent the merger, which impacted its ability to invest. The judge stated, ‘it seems Vodafone faces financial difficulties that are unlikely to materially change absent the merger, and those financial difficulties will limit the extent to which Vodafone can invest in, and grow its business, in the counterfactual.’[35]

However, the merged entity would have an improved ability to fund network investment due to an improved balance sheet, improved access to debt and equity funding, cost synergies and financial benefits from economies of scale.[36] In relation to an improved balance sheet, the judge stated ‘MergeCo would have a stronger balance sheet than either TPG or Vodafone separately. This would provide MergeCo with the capacity to invest strongly in its mobile assets, including by raising equity capital if necessary, and to roll-out 5G services and reduce network congestion more quickly.’[37]

The VHA/TPG decision also asserted that the increased ability to invest would allow a faster rollout of 5G, stating ‘MergeCo’s ability to invest additional capex in its network will enable it to offer high-quality 5G services to customers far sooner than Vodafone or TPG would be able to alone. In doing so, MergeCo will have the opportunity to become a more effective competitive constraint on Telstra and Optus.’[38]

Similarly, in Sprint/T-Mobile, the District Court was concerned with the viability of Sprint as a competitor given its financing issues, stating: ‘The weight of the evidence at trial establishes that Sprint is caught in a vicious cycle caused by its inability to finance meaningful network investment, which perpetuates a low-quality network that drives away customers and limits Sprint’s ability to generate the cash necessary to reduce its financial constraints.’[39]

Noting the narrow applicability of this ‘weakened competitor’ defence,[40] the District Court explored whether there were any competitive means other than the merger to resolve Sprint’s competitiveness issues, ultimately concluding that there was not.[41]

Combining scarce spectrum holdings increases network capacity and lowers network build cost

As noted above, network capacity can be increased by increasing the number of sites, investing in more efficient equipment (eg, upgrading to 5G) or increasing spectrum holdings. Increasing spectrum holdings increases the capacity of the existing network, but also means the capacity provided by any new investments also increases. In this sense, increased spectrum holdings reduce the incremental cost of expanding capacity. This was the case in Sprint/T-Mobile, with the judge stating:

‘The undisputed evidence at trial reflects that combining Sprint and T-Mobile’s low-band and mid-band spectrum on one network will not merely result in the sum of Sprint and T-Mobile’s standalone capacities, but will instead multiply the combined network’s capacity because a technological innovation referred to as “carrier aggregation” and certain physical properties governing the interaction of radios.’[42]

There is a further benefit if the spectrum holdings are contiguous, since this would also eliminate the need for ‘guard bands’ and thus increase the total amount of usable spectrum.[43] VHA and TPG had complementary spectrum holdings in a number of different bands. The decision noted that combining spectrum could lead to benefits, including the reduced need for ‘overhead control’[44] and reduced congestion on the merged network.[45] The VHA/TPG decision explicitly recognised that the increased network capacity resulting from the merger would release funds which could then be redirected to accelerating the 5G rollout:

‘The increase in the capacity of MergeCo’s network will reduce the need to build additional sites or conduct “tactical” 4G upgrades to relieve immediate congestion issues, a substantial proportion of which is inefficient as it would need to be also replaced in the near future. That will release additional capex which can be directed towards accelerating MergeCo’s 5G roll-out.’[46]

Combining spectrum in different bands allows an appropriate balance of coverage and capacity, reducing network build costs

As described above, different spectrum bands have different uses, with low-frequency spectrum providing superior coverage but low capacity and high-frequency spectrum providing poor coverage but high capacity. In Sprint/T-Mobile, T-Mobile had substantial low-band spectrum that Sprint lacked, while Sprint had substantial mid-band spectrum that complemented T-Mobile’s holdings. The parties argued that having a broader spectrum portfolio would allow more efficient spectrum use (ie, using low-band in areas where mid-band could not reach), leading to cost efficiencies, since low-band spectrum can provide greater coverage with fewer sites:

‘Apart from capacity and cost benefits, Defendants claim that New T-Mobile will provide better coverage than Sprint customers currently receive because T-Mobile’s low-band spectrum covers a broader range and penetrates through buildings more effectively than Sprint’s mid-band holdings can. Having a broad range of spectrum would allow New T-Mobile to dedicate each band of spectrum to its best use; it could prioritize the use of low-band in areas that mid-band and mmWave could not reach, while instead prioritizing the other two bands in areas correspondingly closer to the cell sites.’[47]

There are, of course, other impacts on competition besides the investment effects described above, including a reduction in competitive tension from having fewer players in the market (both at the network and retail level). Any pro-competitive effects of investment must be weighed against potential competitive detriments to determine whether, on balance, the merger is pro- or anti-competitive.

Another issue that could arise is whether the efficiencies described above are ‘merger-specific’. Put another way, could the efficiencies be achieved by an alternative arrangement that does not involve a full merger? Indeed, in VHA/TPG the economic expert for the ACCC argued that the benefits described above were not merger-specific given they could be achieved outside of the merger by an NSA. This argument was rejected as it was raised as a hypothetical possibility, without consideration of the specifics of what an NSA might look like between VHA and TPG and whether it would replicate the benefits of the merger.[48]

The potential effects of NSAs on 5G investment

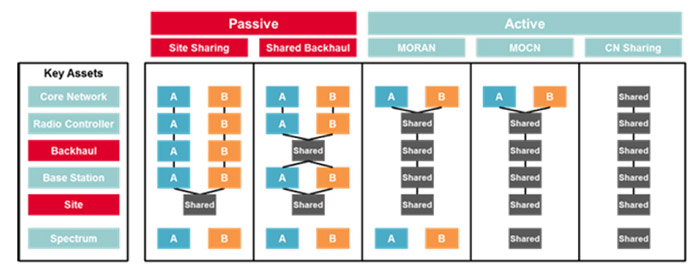

It has been argued by regulators (including the European Commission) that NSAs could allow MNOs to achieve the same efficiencies as a merger, but with less harmful effects on competition at the retail level.[49] For this reason, NSAs have typically been considered less problematic from a competition perspective, particularly those that involve passive, rather than active, sharing of infrastructure. ‘Passive’ refers to sharing passive physical infrastructure (such as sites and towers), whereas ‘active’ refers to sharing the active electrical equipment (such as the radio access network (RAN), which includes the antennas that transmit signals between a cell tower and a consumer’s mobile phone).[50] Within active and passive there are also different NSA models, which involve sharing different assets. Figure 9 provides an overview of models of sharing.

Figure 9: Overview of passive and active infrastructure sharing models

Notes: Site sharing is sharing of physical sites of base stations and shared backhaul is sharing of transport networks from radio controller to base stations. MORAN (Multi-Operator Radio Access Network) is where RANs are shared and dedicated spectrum is used by each sharing operator; MOCN (Multi-Operator Core Network) is sharing of RANs and spectrum; and CN Sharing (Core Network Sharing) is sharing of servers and core network functionalities.

Source: ‘Infrastructure Sharing: An Overview’ (GSMA 2019).

NSAs allow multiple MNOs to use the same physical infrastructure for the provision of mobile services. While such cooperation can generate efficiencies by lowering costs, and thus increasing coverage and/or speeding up network rollout, there may be concerns that such cooperation softens competition by reducing the sharing parties’ incentives to invest and their ability to compete, or raising the risk of tacit coordination between the sharing parties.[51] The net impact of NSAs on competition depends on the balancing of efficiencies and potential anti-competitive effects.

NSAs can generate pro-competitive effects

An NSA reduces the costs of infrastructure as it avoids duplication of some network elements. Depending on the degree of sharing, the sharing parties may only need to build out one set of sites to enable each other to provide coverage to their respective customers. As the unit cost of a higher-capacity shared site is lower than the cost of two standalone sites at half the capacity, there will be lower capex and opex from building one shared network rather than two fully independent networks.[52]

To the extent that the reduced costs of network infrastructure lower MNOs’ marginal (ie, variable) costs, MNOs have greater incentives to pass cost savings on to consumers by lowering prices and/or improving quality.[53] Fixed cost savings can also benefit consumers if, for example, the additional cashflows result in more investment.[54]

The reduced costs of building and maintaining network infrastructure may also enable the sharing parties to increase quality of service by building a denser network than they otherwise would have found profitable to provide individually.

However, NSAs can also give rise to anti-competitive effects

An NSA may result in unilateral effects if it unduly restricts the ability of the sharing parties to differentiate their networks and offers at the retail level, or it may give rise to coordinated effects if the increased transparency and symmetry between the sharing parties facilitates tacit collusion in the retail market.

• Unilateral effects: Under certain circumstances, an NSA may restrict the ability and reduce the incentives of the sharing parties to differentiate their services (by hindering network quality improvements or delaying deployment of new technologies) compared to a counterfactual, where the parties roll out independent networks. The extent to which this may raise concerns will depend on the closeness of competition between the sharing parties and the competitive constraints imposed by remaining MNOs. MNOs with an NSA may still be able to differentiate their services if there are differences in spectrum holdings between the parties and if they retain the operational freedom to deploy additional spectrum, technologies and sites on a standalone basis.[55] The degree of operational freedom depends on the model of network sharing adopted and the assets that are shared (see Figure 9 above). Even with network sharing at the wholesale level, MNOs can still differentiate their services at the retail level.

• Coordinated effects: Awareness of each other’s investment plans (given the need to jointly plan common infrastructure) may increase the shared parties’ ability to predict and respond to the other’s competitive behaviour, which may facilitate tacit collusion. In addition, due to the joint operation of network infrastructure, there may be some commonality of costs, which may further enhance the ability of parties to tacitly collude.[56]

This trade-off between potential pro-competitive and anti-competitive effects was recognised by the General Court in its recent judgment annulling the European Commission’s decision to block the proposed merger of Hutchison 3G UK and Telefónica UK in the UK:

‘According to the Commission’s decision-making practice relating to Article 101(1) and (3) TFEU, network-sharing agreements, which involve the pooling of certain infrastructures, present, from that point of view, competitive risks which vary according to the context and whether the type of sharing is active or passive. Depending on the method of cooperation chosen, the independence of operators and the risk of collusion are more or less prevalent and the risks of undermining competition are more or less significant. At the same time, network-sharing agreements may produce substantial economic benefits in terms of costs savings, improved coverage, and faster network roll-out.’[57]

As explained above, cost reduction is a driver for MNOs to engage in infrastructure sharing. The Body of European Regulators for Electronic Communications (BEREC) considers that the extent of cost savings from network sharing is likely to differ depending on the type of technology that is shared (ie, 5G versus 4G), the areas where sharing takes place (ie, urban versus rural) and when the sharing is implemented (ie, greenfield versus network consolidation).[58] The benefits of infrastructure sharing include potential cost savings and associated acceleration of coverage for areas where the coverage costs for a single operator deployment is high, which often applies to rural areas.[59] Indeed, the European Commission has recognised that coverage in rural areas is a benefit of network sharing.[60] Because of this, regulators have typically considered that NSAs covering rural areas are more justified than those covering more densely populated urban areas. However, with the increased network density of base stations required for 5G, costs of rolling out a 5G network in urban areas are likely to increase and so the potential cost savings associated with network sharing in urban areas will likely be higher. Going forward, the investment costs associated with 5G are likely to result in more NSAs in urban areas.

It is often suggested that passive sharing is likely to be less problematic than active sharing, even though both have similar benefits in terms of reducing the sharing parties’ costs (though there may be greater magnitude of cost savings in the case of active sharing).[61] The concern is that active sharing, which goes beyond the sharing of passive infrastructure (such as sites and masts) and includes active components of the RAN (such as antennas and base stations), may allow sharing parties to weaken competition if active sharing is more likely to restrict their ability to differentiate their networks and services.[62]

Concerns about an inability to differentiate services due to active NSAs may also decline under 5G. This is because under 5G, service characteristics and quality are likely to be determined more by software and the core network (which typically sits outside of NSAs – see Figure 9) than the radio equipment installed at towers.[63] Network slicing will also allow multiple virtual networks to operate over a single physical network.[64] This will allow MNOs using the same network to define different virtual networks with different quality characteristics targeted at different use cases and customers.Therefore, under 5G, parties to an NSA are likely to have more freedom to differentiate their products than would have been the case under previous generations of network technology.

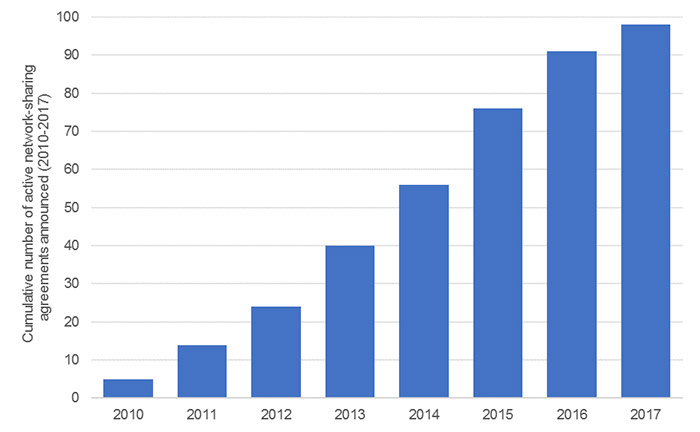

The number of active NSAs globally has increased in recent years (see Figure 10). As NSAs have involved more active sharing elements, regulatory scrutiny of those arrangements has heightened given the greater risk of reduced infrastructure competition between MNOs. Going forward, the pressures on MNOs to collaborate, given the substantial investment costs associated with 5G, are likely to result in active NSAs playing an even greater role in the mobile industry.

This also has implications for the assessment of merger proposals by antitrust authorities: if they consider active NSAs may be problematic from a competition perspective, they may not accept an NSA as a counterfactual for merger analysis.

Figure 10: Active network sharing has become more common worldwide

Source: Adapted from Grijpink et al (see n 12 above).

Competition and regulatory authorities across Europe have assessed the competitive impact of active NSAs.[65] A recent example of an active NSA attracting regulatory scrutiny is the network sharing cooperation in the Czech Republic between O2 CZ/CETIN and T-Mobile CZ.[66] The European Commission opened an antitrust investigation into this NSA in October 2016. In August 2019 the Commission issued a Statement of Objections to the parties, reaching the preliminary conclusion that their NSA restricts competition in breach of Article 101 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.[67] Of the three major MNOs in the Czech Republic, O2 CZ and T-Mobile CZ are the two largest, with their networks serving approximately three-quarters of subscribers.[68]

The European Commission acknowledged that ‘[o]perators sharing networks generally benefits consumers in terms of faster roll out, cost savings and coverage in rural areas’.[69] It added that network sharing is a widespread practice that can facilitate the rollout of networks by reducing costs and, in most cases, creating efficiencies, but in some circumstances, it may have a negative impact on competition.[70]

In this case, however, the Commission has taken the preliminary view that instead of leading to greater efficiencies and higher service quality, the NSA between O2 CZ/CETIN and T-Mobile CZ is likely to remove incentives for the two MNOs to improve their networks and services to the detriment of consumers.[71] However, a recent paper, ‘Cooperation Among Competitors: Network Sharing Can Increase Consumer Welfare’, found that this active NSA has generated consumer benefits through both lower prices and higher quality.[72] Another paper, ‘Horizontal Cooperation on Investment: Evidence From Mobile Network Sharing’, also found that the NSA generated cost savings for the sharing parties, which were passed on to consumers through lower prices and higher network quality.[73]

The impact on 5G investment of a four-to-three merger involving existing network sharing agreements

The proposed acquisition by H3G of O2 in the UK, which was notified to the Commission in 2015, is an example of a four-to-three mobile merger that involved both an assessment of the effects on competition and investment, as well as an evaluation of the impact of the deal on two existing NSAs involving the merging parties.

The merger would have combined the fourth player (H3G) with the first player by subscribers (if O2’s share in the Tesco Mobile joint venture is included), and the second player by revenues. The four MNOs currently in the UK are parties to two NSAs, which enable them to share the costs of rolling out their networks while continuing to compete at the retail level: EE and H3G have shared their networks under the Mobile Broadband Network Limited (MBNL) joint venture; and Vodafone and O2 have brought together their networks to create Beacon.

On 28 May 2020, the General Court annulled the European Commission’s 2016 decision to block the proposed H3G/O2 merger, ruling that the Commission had not proven the transaction would generate non-coordinated (ie, unilateral) effects capable of constituting a significant impediment to effective competition (SIEC).[74] The Commission has since indicated that it will appeal the General Court’s judgment at the Court of Justice of the EU.[75]

One of the three theories of harm identified by the Commission was that the merged entity would have been part of both existing NSAs (MBNL and Beacon) and would have had full overview of the network plans of both network sharing partners (Vodafone and EE – also the two remaining competitors), which would have weakened them and hampered the future development of UK mobile infrastructure, including 5G rollout.[76] In particular, the Commission considered that one of the ways of weakening the competitive position of a given NSA partner (eg, EE) would be to increase the costs of maintaining and improving the network or degrade the network quality of that NSA (eg, MBNL), which would be particularly relevant for the partner in the NSA uninvolved with the merged entity’s consolidated network.

The Commission had argued that while, pre-merger, the partners of each of the two NSAs had an incentive to jointly develop the shared elements of their networks to achieve a better network than the other NSA, this competitive dynamic would be lost post-merger as the merged entity would be party to both NSAs and Vodafone and EE would no longer have a fully committed partner in Beacon and MBNL.[77] After examining the merging parties’ network consolidation plans, the Commission concluded that the merger could: (1) weaken the competitive position of Vodafone and EE and, thus, reduce their competitive pressure; and (2) reduce industry-wide investments in network infrastructure.

In its judgment, the General Court made three broad sets of observations about the Commission’s NSA-related theory of harm and its assessment of the effects of the disruption to the NSAs that would have resulted from the proposed merger.

Alignment of interests between the parties to the NSAs

Firstly, the General Court examined the Commission’s analysis of the need for (and extent of) alignment of interests between the parties to each NSA in order to have a shared network that allows each partner to compete effectively. The General Court noted that the non-merging parties’ (EE and Vodafone) ability to compete and incentives to invest would not depend decisively on the merged entity’s investment decisions or on cost increases, but instead on the level of competition that these competitors would face, their financial resources and their strategies.[78]

In the General Court’s view, the fact that an NSA may result in pro-competitive effects, thus counteracting the restrictions it contains, does not necessarily mean that its termination, renegotiation or each subsequent alteration to its balance following a merger may necessarily be characterised as an SIEC.[79] Thus, the General Court ruled:

‘Therefore, it must be held that a possible misalignment of the interests of the partners in a network-sharing agreement, a disruption of the pre-existing network-sharing arrangements the duration of which was extended for the benefit of Three, or even the termination of those agreements does not constitute, in the present case, and as such, a significant impediment to effective competition in the context of a theory of harm based on non-coordinated effects.’[80]

Effects of the merger on the competitors that are partners in the NSAs

Secondly, the General Court examined the European Commission’s assessment of the effects of the merger on the two competitors and NSA partners, EE and Vodafone, in light of the merged entity’s network consolidation plans. The General Court ruled that the Commission had failed to prove to the requisite legal standard that the alleged increase in EE and Vodafone’s fixed and incremental costs would lead to lower investments, a deterioration in the quality of services or, if the higher costs were passed on to consumers as higher prices, a decrease in competitive pressure exerted by EE and Vodafone.[81] The General Court also found that a reduction in the competitive pressure that EE or Vodafone were capable of exerting is not, in itself, sufficient to establish an SIEC.[82]

Effects of increased transparency on overall network investments

Finally, the General Court examined the European Commission’s concern that the resulting increased transparency of each MNO’s investment strategy would reduce EE and Vodafone’s unilateral incentives to invest proactively in new technology (before any initiative by the merged entity to invest first) and hence reduce their competitive pressure. The General Court ruled that, by failing to set out the appropriate timeframe for establishing the existence of an SIEC, the Commission had erred in law in finding that the increased transparency of MNOs’ overall investments brought about by the NSAs would reduce MNOs’ incentives to invest in their networks.[83]

The Commission analysed: (1) the merger’s short- and medium-term effects in light of the temporary overlap of the two NSAs; and (2) the merger’s medium- and long-term effects in light of the merged entity’s network consolidation plans.[84] However, in the General Court’s view, the Commission did not take into account that the merging parties would not maintain two separate networks in the long term.[85] Therefore, the General Court rejected the Commission’s finding on the effect of increased transparency on overall network investments, which was based on the assumption of the existence of two separate networks.[86]

In addition, the Commission did not appear to consider the long term as the appropriate timeframe for assessing the effects of the merger.[87] The General Court, however, disagreed:

‘The Court finds that the analysis of the effects of a concentration on an oligopolistic market in the telecommunications sector which requires long-term investment and where consumers are often tied by contracts over several years is a dynamic prospective analysis which requires account to be taken of any coordinated or unilateral effects over a relatively long period of time in the future.’[88]

Conclusion

Both mergers and NSAs between MNOs have the potential to benefit consumers through increased investment and the dynamic competition benefits they bring. In particular, by improving the economics of 5G investment, they may increase the magnitude of investment and the speed with which 5G is rolled out. However, they may also reduce competitive tension, particularly in a more static sense, between MNOs. The overall effect on investment and consumer welfare will depend on the specific facts and circumstances of each case.

The cases we have discussed highlight that for both mergers and NSAs, whether there is a positive impact on investment depends on (among other things):

• the merging or sharing parties’ financial position and ability to invest; and

• the extent of the synergies created by combining spectrum and network assets.

For NSAs, the degree of cost savings achieved (and potential for increased investment) will depend on the type of network sharing arrangement, in particular: the type of infrastructure that is shared (ie, passive versus active), the type of technology (ie, 5G versus 4G), the areas where sharing takes place (ie, urban versus rural) and when the sharing is implemented (ie, greenfield versus network consolidation).

Given the substantial investment costs associated with 5G, and the resulting pressures on MNOs to collaborate, active NSAs and NSAs covering urban areas are likely to play an increasingly important role in MNO plans for rolling out 5G networks. This is likely to attract greater regulatory scrutiny given the potential competition concerns raised by these types of NSAs. Counterbalancing this, the technical characteristics of 5G (virtualisation and network slicing) may lessen concerns that NSAs will limit the ability of MNOs to differentiate their services.

Economic analysis and evidence have an important role to play in evaluating this trade-off between efficiency gains and anti-competitive effects arising from consolidation and cooperation between MNOs, and assessing the overall impact on investment and competition, as demonstrated in the General Court’s recent H3G/O2 judgment.

About the authors

Dr Will Taylor is an associate director in NERA Economic Consulting’s Antitrust and Competition, Energy and Communications, Media and Internet Practices in Auckland and Sydney, Australia.

Adrien Cervera-Jackson is an associate director in NERA Economic Consulting’s Antitrust and Competition Practice in London, UK.

[1] Dr Will Taylor is an associate director in NERA Economic Consulting’s Antitrust and Competition, Energy and Communications, Media and Internet Practices in Auckland and Sydney, Australia. Adrien Cervera-Jackson is an Associate Director in NERA Economic Consulting’s Antitrust and Competition Practice in London.

The authors would like to thank Anca Cojoc, Hans Ihle, James Mellsop, Grant Saggers and Bruno Soria for their helpful comments. Valuable research assistance was provided by Kate Eyre and Barbara Kaleff. Any mistakes are the authors’ own. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of NERA Economic Consulting or its clients.

[2] ‘Passive’ refers to sharing passive physical infrastructure such as sites and towers, whereas ‘active’ refers to sharing the active electrical equipment such as the radio access network (RAN), which includes the antennas that transmit signals between a cell tower and a consumer’s mobile phone.

[3] ‘Joint venture’ refers to MNOs forming a joint venture company to operate the shared network assets and provide services to the sharing parties, whereas ‘geo-split agreement’ refers to the geographic separation of the shared network with each MNO operating the network in its respective area.

[4] Eg, the towers or sites where equipment is installed and from which it broadcasts.

[5] Optus owns just 20MHz of low band spectrum, while the other two main players, Telstra and VHA/TPG, own 60 and 50MHz respectively. See Submission in response to ACCC Discussion Paper – Spectrum Allocation Limits – 26 GHz Band, Public Version (Optus 2020) para 22.

[6] Patrick Welsh, ‘Verizon’s Millimeter Wave Deployment Experiences’ (Presentation at 15th European Spectrum Management Conference, 25 June 2020), available at: www.youtube.com/watch?v=MQ5u8guwPGA, accessed 2 October 2020.

[7] GSMA, 5G Spectrum: GSMA Public Policy Position(GSMA March 2020) p 2.

[9] Where fixed wireless access refers to providing a fixed broadband service using the mobile network.

[10] See Jeffrey A Eisenach and Robert B Kulick, ‘Economic Impacts of Mobile Broadband Innovation: Evidence from the Transition to 4G’ (2020) SSRN. According to Eisenach and Kulick, 5G will likely enhance the consumer-oriented mobile broadband use cases made possible by 4G and will extend commercial application of mobile wireless technology to business and industrial use cases not possible with previous technology, including enabling the IoT. They estimate that if 5G adoption follows the same path as 4G adoption, at its peak 5G will contribute approximately three million jobs and $635bn in GDP to the US economy. See also Majed Al Amine et al, ‘Smart Cities: How 5G Can Help Municipalities Become Vibrant Smart Cities’ (Accenture Strategy 2017) and ‘Impacts of 5G on Productivity and Economic Growth’ (Australian Bureau of Communications and Arts Research 2018).

[11] The C-Band refers to 3.5GHz spectrum, which is expected to be the key international band for initial 5G roll outs.

[12] Ferry Grijpink et al, ‘The road to 5G: The inevitable growth of infrastructure cost’ (McKinsey & Company, 23 February 2018).

[14] ARPU can fall either because consumers purchase lower-priced, lower-quality plans, or because prices for a given level of quality fall.

[15] Eg, when Vodafone launched 5G offers in the UK in 2018 and when T-Mobile launched its 5G offer, neither charged more for 5G. See John McCann, ‘Vodafone 5G turned on in 7 cities and it’s the same price as 4G’ (TechRadar, 3 July 201