A state of emergency for US democracy and rule of law

Michael Goldhaber, IBA US CorrespondentWednesday 10 June 2020

Pic: A healthcare worker takes a break at the Tulane Medical Center in New Orleans, US, 14 April 2020. REUTERS/Carlos Barria

As the United States enters election season in a state of Covid-induced emergency, Global Insight assesses the dangers of President Trump abusing the vast emergency powers – 123 of them – at his fingertips.

The foundational fear of the United States Constitution is a President who commences as a demagogue and ends as a tyrant. Alexander Hamilton first warned against dangerous ambition lurking behind a President’s mask of right for the people in The Federalist Papers. University of Chicago Law professor Eric Posner defines a demagogue as a charismatic narcissist who gains power by appealing to public fears rather than advancing public good, undermining expert institutions with contempt for rules, norms and basic civility. President Donald Trump qualifies as a demagogue for Posner. But the question remains, as the presidential election approaches in a state of emergency, has this President ended as a tyrant?

When asked in the 2016 final debate whether he’d accept the outcome of the election, candidate Trump replied, he’d keep the American people ‘in suspense.’ We still don’t know how President Trump would react to an Electoral College loss. He has never accepted his popular vote loss – always repeating the lie that millions of Democrats voted illegally. When President of the People’s Republic of China Xi Jinping jettisoned term limits in 2017, President Trump gushed: ‘He’s now president for life, I think it’s great. Maybe we’ll have to give that a shot someday.’ Now President Trump enters the 2020 election season behind in the polls, with vast emergency powers at his fingertips. Will he assent to a peaceful democratic transition? We’re still in suspense.

Elizabeth Goitein, Director of Brennan Center for Justice’s Liberty & National Security Program, has continuously cautioned that the President’s emergency authority lies about ‘like a loaded weapon.’ Upon declaring a health emergency in mid-March, President Trump gained access to 123 statutory powers. Secret Presidential Emergency Action Documents, first developed during the Cold War, are executive orders and messages to Congress which are quietly updated by each administration. In the 1970s, the Documents allowed the White House to keep a list of subversives, suspend habeas corpus and declare martial law. And there are the scarily broad powers Congress has openly granted. The Insurrection Act of 1807, which the President has already threatened to invoke in response to the nationwide police brutality protests, allows the President to deploy troops to quell ‘domestic violence’ or ‘conspiracy.’ Section 706 of the Communications Act, enacted in the heyday of radio in 1934, allows a president to take control of any facility for wire communication – potentially allowing an internet shut-down today.

Although the National Emergencies Act of 1976 provides for congressional review of emergency powers every six months, Congress has debated only one of 64 declared emergencies, and failed to halt it. Most still remain in effect, reviewed only by a President’s devotion to democracy.

President Trump often casts doubt on his devotion to democracy. He congratulated Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan for consolidating autocracy by holding an irregular vote during an emergency. He congratulated Russian President Vladimir Putin on an obviously fraudulent re-election, with briefing papers that read ‘DO NOT CONGRATULATE.’ President Trump called North Korean Supreme Leader Kim Jong-Un ‘a pretty smart cookie’ for winning a power struggle with his uncle – whom he executed. That such a primitive method of succession impresses President Trump is especially troubling given that he’s repeated the myth that Kim publicly displayed his uncle’s severed head.

Was President Trump kidding when he said of autocracy, ‘Maybe we’ll have to give that a shot some day?’ If so, it’s a joke he finds deeply amusing and riffs on at his most unfiltered forums. ‘A lot of my critics say, “You know he’s not leaving,”’ he told a friendly crowd this December. ‘So now we have to start thinking about that because it’s not a bad idea.’ At a December rally in the rural State of Pennsylvania, the President joked that he’d maybe leave office in ‘five years, nine years, 13 years, 17 years, 25 years, 29 years.’ At a South Carolina rally, just before the lockdown, the President fondly recalled his 14-year-run as host of the reality show The Apprentice. He free-associated about his tenure as President: ‘Of course you want to upset them. Oh, they go crazy when you say it. When you say to them five more years, so it’s five, but you then say maybe nine, maybe 13, maybe 17, maybe 21. Let’s do this. Let’s term limit ourselves at 25 years. No more than 25 years.’ In each instance, the crowd met the President’s musings with cheers and applause.

Political scientist Yascha Mounk has cataloged the moves of authoritarian populists. By his reckoning, President Trump has used five of the six: spreading disinformation; scapegoating minorities; assailing his critics; politicising institutions; and strengthening the executive. The only play left in the demagogue’s playbook is corrupting elections. Goitein predicts gravely: ‘If the President’s back is against the wall when the election comes, he will do whatever he thinks he needs to do to exploit the Covid-19 pandemic to make sure he wins.’

If the President’s back is against the wall when the election comes, he will do whatever he thinks he needs to do to exploit the Covid-19 pandemic to make sure he wins

Elizabeth Goltein

Director, Liberty & National Security Program, The Brennan Center for Justice

Cancelling election day

The obvious way to fiddle with a democratic transition haunts the President’s opponent. ‘Mark my words,’ Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden said in April, ‘he is going to try to kick back the election somehow – come up with some rationale why it can’t be held.’ The President shot that theory down the next day: ‘I’ve never thought of changing the date of the election. Why would I do that?’ His son-in-law and senior advisor, Jared Kushner, muddied the waters: ‘I’m not sure I can commit one way or the other to a date,’ but swiftly backed down. Whatever their intent, Biden needn’t worry. ‘There are no emergency powers,’ says Goitein, ‘that would allow the President to alter election procedures or change the date.’ Election day is fixed by federal statute as the first Tuesday in November. Voting rules are set by each state, and only Congress has the power to override them.

It would be feasible for a state to seize on an autumn wave of Covid-19 to cancel its direct popular election. This would allow the state legislature to directly appoint a slate of Electoral College electors. ‘It’s an obvious strategy we’re facing,’ says Harvard Law School Professor of Law and Leadership Lawrence Lessig – and it would be perfectly constitutional.

But the President opposes mail-in voting to Lessig’s dismay. Luckily, according to a Brennan Center for Justice study, two-thirds of states already allow mail-in voting without requiring any excuse. The majority of the rest accept fear of Covid-19 as an excuse for voting by mail, or have friendly case law. Texas is the most worrying state – however, the Brennan Center for Justice recently won an injunction, pending appeal, that fear of Covid-19 must be accepted as an excuse for absentee voting in the state. Of the five states left, where elections might conceivably be halted (Kentucky, Mississippi, South Carolina, Tennessee, and perhaps Louisiana), none are presidential battlegrounds. ‘In all the key states all voters already have a no-excuse mail-in option,’ says counsel Max Feldman of the Brennan Center for Justice’s Voting Rights and Elections Program.

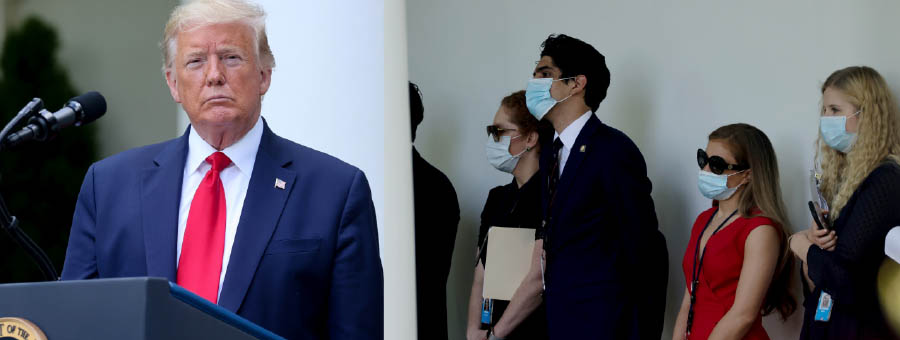

Masked White House Staff listen to a presidential speech on pharmaceutical negotiations during the Covid-19 pandemic. Washington, US. 26 May 2020. REUTERS/Jonathan Ernst

Pandemic voter suppression

Southern Democrats and modern Republicans have a long and dishonourable tradition of suppressing the vote, whether by lynch mob, literacy test, voter ID, propaganda or poll closures. But no more fiendish tool of voter suppression has ever been devised than the current coronavirus outbreak. President Trump, argues Goitein, knows that suppressing the vote is the only way he wins. And the best way to guarantee a low vote count is to create postal chaos amid a pandemic.

Before Covid-19, Goitein suggested all sorts of ways that the President might conceivably abuse emergency powers to suppress the vote. A few weeks before the 2018 vote, the Federal Emergency Management Agency texted a test ‘Presidential alert’ to 300 million US mobiles. Could the President hijack this new system to encourage fear and confusion on election day, or simply instruct all Americans to ‘avoid crowds’? Could the President declare a voter fraud crisis and try to seize the assets of ‘get out the vote’ groups? Might the President use domestic unrest that he himself encourages by tweet as an excuse to mobilise the military or law enforcement in the hopes of intimidating immigrant or minority voters? It’s illegal for law enforcement to be present at polls, but that didn’t stop the President from tweeting before the 2018 elections: ‘All levels of government and law enforcement are watching carefully for VOTER FRAUD.’ The night before election day, he again warned: ‘Law Enforcement has been strongly notified to watch closely for any ILLEGAL VOTING.’

With the distinct possibility of Covid-19 spiking this autumn in the Democrats’ key urban strongholds, one needn’t reach for fanciful scenarios of voter suppression. A primary election was held this spring in the mid-western State of Wisconsin while it underwent a relatively modest outbreak (4.2 deaths per 100,000 in mid-April). Republican officeholders refused to limit the election to mail-in ballots, sharply cutting the number of open polling places in cities, and fought against giving the election authorities flexibility to handle an unprecedented flood of mail-in ballots for which they were logistically unprepared. Thousands of Wisconsin voters were disenfranchised by the refusal of the US Supreme Court’s conservative majority to let a federal judge extend the absentee ballot deadline past election day. Almost three-quarters of Wisconsin voters chose mail-in ballots over polling booths, and many still contracted Covid-19.

In Congress, Republicans are blocking a Democratic bill, co-sponsored by Senator for Minnesota Amy Klobuchar, that aims to make in-person voting safer and less scary amid the pandemic. Among other things, it would enlarge polling locations, sanitise the booths, outfit staff with protective gear and recruit younger poll workers. At the same time, Republicans in Congress are blocking Democratic efforts to require ‘no-excuse’ mail-in voting in every state. To date, Republicans have agreed to only a fraction of the funds Democrats have proposed to strengthen the states’ mail-in capacity and bail out the US Postal Service.

Nine, maybe 13, maybe 17, maybe 21. Let’s do this. Let’s term limit ourselves at 25 years

US President, Donald Trump

When House Democrats initially tried to insert national vote-by-mail provisions in the $2tn Covid-19 relief bill, the President refused. The President has spent a lot of energy discrediting mail-in voting as a ‘terrible thing’ rife with fraud. But he also let it slip that helping people vote would be ‘extremely devastating to Republicans.’ The President clarified: ‘The things they had in there were crazy. They had things, levels of voting that if you’d ever agreed to it, you’d never have a Republican elected in this country again.’

In fact, the partisan tilt of voting-by-mail is historically unclear. This year it will depend mostly on the geographical pattern of Covid-19 on election day – and that’s unknowable. In the mail-dominated Wisconsin primary, the Democratic candidate won the main contest despite the chaos. The Democratic edge is attributed partly to a superior ‘get out the vote’ push, and partly to Democrats fearing the virus more according to surveys.

But Michael Steele, a former chairman of the Republican National Committee, writes that vote-by-mail only boosts overall turnout. It’s attractive to citizens who are elderly or rural – who lean Republican – or the politically disengaged. So ‘the idea that stopping mail will have a predictable partisan benefit is outlandish,’ says Feldman. Less obviously, Steele argues that more voting by the disengaged would be healthy for both parties. Low-turnout primaries stoke extremism because they’re dominated by ‘base voters.’ Improving ballot access for citizens who aren’t obsessed by politics would have a welcome moderating effect.

Giving every voter the right to vote by mail would be nice. But in the swing states, voters already have that right. The bigger worry is whether they’ll be able to exercise it. The frightening fact is that no swing state has experience handling mail-in ballots of this scale. The three states that decided the 2016 election – Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin – are especially at risk because they historically had low rates of absentee voting. America’s crucial election need in 2020 is to strengthen capacity to handle the coming flood of mail-in ballots. ‘The question is not whether states will allow mail-in voting,’ says Feldman.

‘The question is how prepared states will be for the inevitable surge.’ Election officials urgently need funds to print tens of millions of absentee ballots, buy high-speed scanners and pay postage. ‘Some states are facing an order of magnitude more absentee ballots than they are prepared to process,’ says Michael Morley of Florida State University College of Law, who studies election emergencies.

A registered Republican, Morley stresses that the virus is far likelier to suppress the vote through logistical chaos than through chicanery or fraud by either Democrats or Republicans. While mail-in ballots are relatively more prone to fraud, he says, the larger truth is that voter fraud of any kind is rare. ‘The voter fraud narrative,’ says Feldman, ‘has been disproven and discredited over and over again.’ State election officials from both parties know that, and despite the President’s entreaties, they’re busy ramping up their mail-in capacity. ‘The overwhelming majority of election officials from both parties, including ones elected on partisan tickets, are dedicated professionals devoted to fair elections,’ says Morley. The problem is they’re strapped for resources. As a banal instance of emergency chaos, he points to a New Jersey district, swamped by Superstorm Sandy in 2012, that used fax machines and ran out of ink.

A family waiting for donated groceries from a food bank during the Covid-19 pandemic. Kentucky, US. April 2020. REUTERS/Bryan Woolston

As part of the giant relief Act in March, Congress approved $400m for election preparation. But that’s only ten per cent of the need, according to the Brennan Center for Justice. House Democrats allotted an extra $3.6bn in their new jumbo relief bill, but Senate Republicans greeted this as dead on arrival. It’s anyone’s guess if more election funding will materialise.

Devastated by the lockdown, the US Postal Service expects to be financially illiquid by 30 September – just in time for the deluge of mail-in ballots. ‘It’s unconscionable in this situation not to fund the postal service at a level that allows it to serve all Americans,’ says Feldman.

The post office has asked for $75bn. The first big relief Act only included a $10bn loan, which the President is using as leverage to control postal policy by imposing conditions. House Democrats also proposed an additional $25bn outright as part of the May bill which was scorned by Senate Republicans. Under pressure in May, the post office picked a Trump donor who served as finance chair of the Republican National Convention, Louis DeJoy, as postmaster general. ‘For vote by mail,’ tweeted ‘NeverTrump’ Republican, Weekly Standard founder William Kristol, ‘this seems like putting a fox in charge of the hen house.’

Disinformation and meddlesome Russia

Of course, America’s voting system was vulnerable before Covid-19 jumped the species barrier. ‘There’s no rule that says you can only have one election emergency at a time,’ notes Morley. On the contrary, the US is contending with cyber-attacks and disinformation while it’s contending with the pandemic. Foreign actors with the requisite skills and a motive to meddle (whether for or against the President) include China, Iran, North Korea and Russia.

Former special counsel for the US Department of Justice Robert Mueller concluded in his report that Russia’s interference in the 2016 US election was ‘sweeping and systematic.’ In November 2018, then-US Secretary of Defense James Mattis confirmed that Putin ‘tried again to muck around in our elections and we are seeing a continued effort on those lines.’ In July 2019, a bipartisan Senate Intelligence Committee report found that Russia tampered with election systems in all 50 states in 2016. The next day, Mueller testified that ‘they’re still doing it as we sit here.’ But President Trump purports to disbelieve Mueller and the intelligence community. ‘President Putin says it’s not Russia,’ he said at their Helsinki summit. ‘I don’t see any reason why it would be.’ His son-in-law dismissed Russian social media posts reaching 126 million Americans by November 2016 as ‘a couple of Facebook ads.’

In 2018, then-US Secretary of Homeland Security Kierstjen Nielsen tried to make 2020 election security a cabinet priority – but stalled out when the White House chief of staff Mick Mulvaney reportedly told her it ‘wasn’t a great subject’ to bring up with the President. In 2019, bipartisan Senators pushed bills that would force Facebook to disclose the buyers of political ads, improve cyber-intelligence sharing by state election officials and incentivise states to adopt backup paper ballots. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell blocked all action. Apparently stung by being dubbed Moscow Mitch, he then agreed to an extra $250m in election security funds, bringing the 2020 total to $425m.

A single family-sized portion of donated food is seen at an emergency drive-through food and toilet paper distribution hosted by the San Diego Food Bank amid the Covid-19 outbreak, in Chula Vista, California, US, April 2020. REUTERS/Bing Guan

Despite this half-hearted national response, the US has made decent progress in electoral cyber-security at the state level. Only eight states still rely on paperless electronic voting machines. The key purple swing states of Florida and Michigan have made significant progress since 2016, according to the Brennan Center for Justice, as have the recently-purple states of Colorado, Nevada, Ohio and Virginia. Of the eight states that still have paperless polls, none are expected to be closely contested for President, except perhaps Texas (which would only be contested in a national landslide). Still, foreign meddlers could make plenty of mischief below the presidential level in Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, New Jersey, Tennessee and Texas.

The Covid-19 crisis makes the ground fertile for disinformation on when, where and how to vote

Michael Morley

Assistant Professor, College of Law, Florida State University

The good news is that the virus-driven shift toward mail-in ballots makes elections less vulnerable to hacking – as Morley says, ‘You can’t hack paper.’ The bad news is that voters using novel procedures are more vulnerable to disinformation. ‘The Covid-19 crisis makes the ground fertile for disinformation on when, where and how to vote,’ says Morley. For instance, in 2016, Russian Twitter and Facebook accounts suppressed the vote by encouraging gullible Democrats to ‘text to vote’ or ‘vote at home’ on election day (which were both impossible). It’s by no means a stretch to envision foreign or domestic dirty tricksters planting news stories on election day about infection rates spiking, and the polls in Democratic precincts emerging as hot spots.

The morning after election day

Unless the 2020 presidential race is a blowout, the winner won’t be known on Wednesday morning. The swing states are ill-prepared for vote-by-mail and the Supreme Court ruled this April that votes postmarked ‘election day’ must be counted. The stage is set for the tally to drag on for days or weeks, while lawyers litigate every vote at the margin. In the Wisconsin primary, Democratic lawyers pre-drafted affidavits for hundreds of voters who had requested mail-in ballots, and never received them. A highly plausible nightmare scenario, says Morley, is that the President leads in the state throughout the television coverage on Tuesday evening, only to fall behind when mail-in ballots are fully counted. That’s what happened in the 2018 Arizona Senate race, and the President pounced with accusations of voter fraud. ‘We’re already seeing significant efforts by the President and his allies to discredit mail-in ballots,’ notes Feldman. ‘They’re spreading a false narrative of voter fraud to sow distrust in our election process.’

People gather at the entrance for the New York State Department of Labor offices, which closed to the public due to the Covid-19 outbreak in the Brooklyn borough of New York City, US, March 2020. REUTERS/Andrew Kelly

What’s the endgame? Imagine the President tweeting nonstop that he’s the ‘VICTIM OF A COUP.’ Imagine a post-election rally in the Florida Panhandle, where he rambles about ‘all the tough guys’ being on his side, and how ‘people say they love the Second Amendment, but I’d never say that or I’d get in trouble, I’d never say that.’ Russian trolls would create a viral meme on Facebook of President Trump hugging a US flag and mouthing the catchphrase of Charlton Heston clutching his shotgun: ‘From my cold dead hands.’ As historian Timothy Snyder has shown, it is Russia’s avowed doctrine to harness ‘the protest potential of the US population, and encourage Americans’ tendency toward “destructive paranoid reflection”.’ Facebook would discreetly appoint a panel to draft its contrite testimony during the second Trump administration.

It’s chilling to imagine. But, even after surveying two centuries of US demagoguery, Posner is sceptical that President Trump or his admirers would go that far: ‘Maybe I’m too optimistic but I simply don’t believe he’ll try to create a civil insurrection. I don’t believe that even his staunchest supporters would respond by taking up arms. There just isn’t that tradition in the US. I don’t think his hold on people is that powerful,’ says Posner.

For her part, Goitein can see the President fomenting street protests while the outcome of the election hangs in the balance. But civil war would not be their goal. Rather, they would aim to pressure institutions to resolve a contested election in their favour, or else lay the groundwork for their movement’s democratic return in 2024.

Goitein and Posner spoke before President Trump threatened to invoke the Insurrection Act to quell the protests following the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, as this edition went to press. But there is comfort to be found in the broad-based outcry elicited by the President’s military threat. Two retired chairs of the Joint Chiefs of Staff – as well as Trump’s revered first Defense Secretary James Mattis – rebuked the President and his current Defense Secretary Mark Esper for speaking of the states as a ‘battlespace’ to be ‘dominated.’ Secretary Esper swiftly reversed gears, and announced that he opposes invoking the Insurrection Act.

When push comes to shove, Goitein expects that Congress and the Supreme Court will abide by the rule of law and – although she cannot rule it out – she does not expect President Trump to declare martial law. By almost any definition, President Trump has commenced a demagogue, and continued a demagogue. Yet even the Cassandra of emergency powers remains hopeful that he will not end a tyrant.

Michael Goldhaber is the IBA’s US Correspondent. He can be contacted at michael.goldhaber@int-bar.org