Save the children: the fight for juvenile justice

Emad Mekay

Populations prey to a combination of political upheaval and autocratic regimes across the Middle East face appalling consequences. Global Insight assesses the troubling and persistent use of the death penalty, particularly for minors.

Iran’s recent decision to execute three individuals for crimes committed when they were under 18 prompted the United Nations to issue a heated rebuke. ‘The execution of juvenile offenders is unequivocally prohibited under international law, regardless of the circumstances and nature of the crime committed,’ stated Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights.

‘The imposition of the death penalty on people who committed crimes when they were under 18 is in clear violation of Iran’s obligations under two international treaties that it has ratified and is obliged to uphold – namely the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the Convention on the Rights of the Child.’

Tehran’s response was swift: the Islamic Republic was being singled out for its assertive foreign policy and major rights offenders in the Middle East are spared similar reproach. Secretary of Iran’s High Council for Human Rights Mohammad-Javad Larijani called on the UN Human Rights Council ‘to discard dual standards and politically-motivated actions’.

The impassioned exchange highlighted the deteriorating conditions in the Middle East, including the use of the death penalty in countries like Egypt, Iran and Saudi Arabia, and the growing links between rights violations and the region’s worsening political instability.

The executioners

There’s a consensus among activists that, despite worsening civil liberties across the Middle East, Iran is a major culprit when it comes to capital punishment, particularly against minors (under 18), defined by the UN as children. Norway-based organisation Iran Human Rights (IHR) counts 55 juvenile offenders executed in Iran since 2008. Activists and non-governmental organisations that advocate for the abolition of the death penalty altogether, such as Amnesty International, have repeatedly labelled Tehran as one of the main executioners of juvenile offenders, along with China and Saudi Arabia.

‘In the Middle East, only Iran executed juvenile offenders in 2017 and 2018. Amnesty International believes juvenile offenders are still on death row in Iran and Saudi Arabia,’ says Natacha Bracq, a programme lawyer at the International Bar Association’s Human Rights Institute (IBAHRI).

The UN notes that three people aged 15 have already been executed in Iran this year. This compares with five for the whole of 2017. Already, 80 individuals are on death row after being sentenced for crimes they committed when they were under 18.

‘Iran leads the Islamic capital punishment chart in all categories year after year, executing between 375 and 700 individuals per year,’ says John Vernon, a member of the IBA Human Rights Law Committee Advisory Board. ‘China leads the world in executions of children and adults, despite the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) Article 6(5) prohibition on executing anyone under the age of 18.’

The West tends to overlook regimes such as Saudi Arabia – economic interests play a major role

Javaid Rehman

UN Special Rapporteur on human rights in Iran; member, IBA Task Force on International Terrorism

US Ambassador to the United Nations Human Rights Council (2014–2017)

New York-based Human Rights Watch has long called on Iranian authorities to disavow the practice for several reasons. The penalty is irreversible and inhumane, and convicted minors often lack maturity, a true sense of responsibility, and are often susceptible to peer pressure.

The Iranian Ministry of Foreign Affairs didn’t respond to questions from Global Insight over the use of the death penalty but the Islamic Republic News Agency (IRNA) has released statements from officials that Tehran introduced several legal protections for children in response to the international outcry. Iranian officials are quoted as saying that improvements in the 2013 penal code prohibit executing juvenile offenders for certain types of crimes, including drug-related offences.

Some drug offences previously punishable by the death penalty are now subject to a prison term instead. Iran says this could positively affect dozens of inmates on death row. Handing out a death sentence against a child who didn’t understand the consequences of a crime they committed is now left up to the discretion of the judge, under Article 91 of the amended code. The reforms allow the courts to consider input from forensic doctors or use other means to establish whether a defendant fully comprehended the result of their actions.

International human rights groups remain unimpressed as, despite improvements, the mandatory death sentence is retained for a range of drug-related crimes. Mahmood Amiry-Moghaddam is Director of the IHR, which conducts much of its research and data collection through contacts with rights activists, families of death penalty convicts and prisoners inside Iran. He tells Global Insight that the arguments of Iranian officials are not accurate. ‘Unfortunately that’s not true,’ he says. ‘The number of juvenile executions has actually increased since 2013. Iran has been the biggest executioner of the Middle East for several years but the execution numbers increased dramatically after the post-election protests in 2009 and are still very high.’

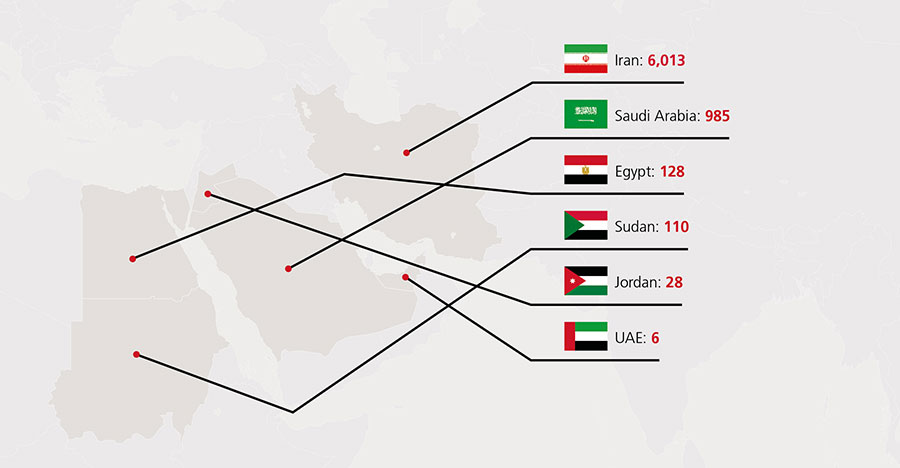

Number of executions reported between 2008–2017

(Numbers for Iran are collected by IHR, while the other numbers have been reported by human rights organisations such as Amnesty International and Cornell Center on the Death Penalty Worldwide. In several of the countries, the exact number is thought to be higher due to the secrecy and lack of transparency)

Indeed, both Amnesty International and IHR report that, from 2014, the year after Tehran amended the law, to the end of 2017, Iran hanged at least 25 people for crimes committed when they were children. IHR reports that at least 5,300 people have been executed in Iran between 2010 and 2018.

Human Rights Watch saw little serious impact as a result of the amended law on executions. ‘Iran seems intent on erasing any positive impression gained from modest reforms to its drug execution laws last year by hanging several child offenders in a bloody start to 2018,’ says Sarah Leah Whitson, Middle East Director at Human Rights Watch. ‘When will Iran’s judiciary actually carry out its alleged mission, ensuring justice, and end this deplorable practice of executing children?’

The government’s defence of capital punishment is also criticised based on its clampdowns on rights defenders. Amiry-Moghaddam says, ‘Iranian authorities call it a politically motivated criticism to avoid taking responsibility for their disastrous human rights record. Inside Iran, they put in prison Iranian human rights defenders for the same criticism. Narges Mohammadi and Atena Daemi have been sentenced to ten and seven years in prison respectively for peaceful activities against the death penalty and for human rights.’

Saudi Arabia versus human rights groups

Like Iran, Saudi Arabia is another Middle Eastern regime that has riled international rights groups for years over a host of grave civil liberties abuses, including the death penalty for minors.

Reprieve, a London-based group that litigates on behalf of death row inmates, has called upon the British government to help end Saudi execution of minors. ‘Ali al-Nimr, Dawood al-Marhoon and Abdullah al-Zaher are facing imminent execution,’ says the group, which urges the UK Prime Minister ‘Theresa May: Help stop execution of children in Saudi Arabia.’ Director of Reprieve Maya Foa tells Global Insight that the three convicts, arrested when they were teens, could be put to death at any time. ‘The UN has called on Saudi Arabia to immediately release them but no steps have been taken to do so,’ she says.

According to Reprieve, eight children currently face beheading for political protests against practices of the Saudi ruling family in the conservative kingdom. ‘All of them could be beheaded without notice or even their families being told,’ says Foa.

Reprieve estimates that, between 2013 and 2016, 12 people were executed who may have been under the age of 18 when committing offences. This includes Sri Lankan domestic worker Rizana Nafeek, who is believed to have entered Saudi Arabia on forged documents to show she was an adult, executed in 2013, and Ali al-Ribh, who was executed en masse in 2016 for attending protests at the age of 17.

Children over 15 years are tried as adults in Saudi Arabia and can be executed after what rights advocates say are trials often lacking fairness and guarantees of due process. ‘The UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, in charge of reviewing Saudi’s respect of the Convention, urged Saudi in 2016 to immediately halt the execution of people who were below the age of 18 at the time of the alleged commission of the offence,’ says Bracq.

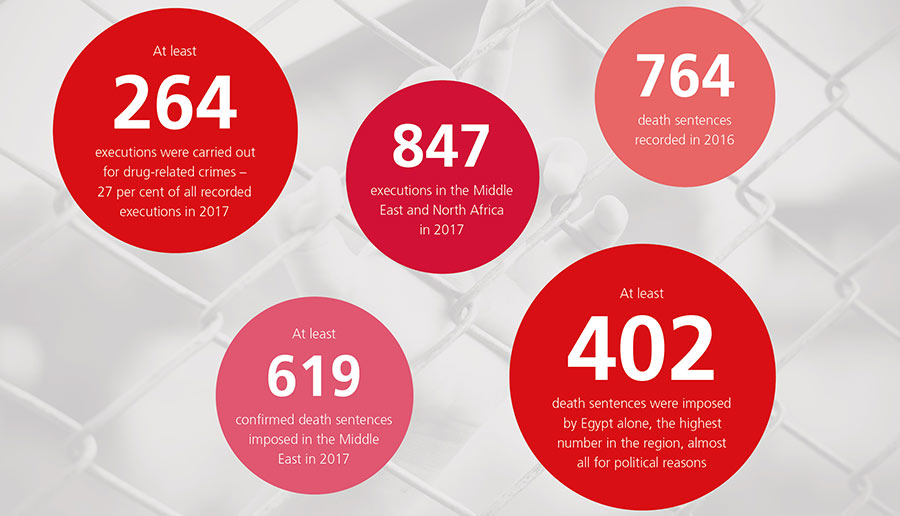

Source: Amnesty International

But, despite international pleas, Saudi Arabia, an oil-rich country whose wealth gives it phenomenal power, persists in using capital punishment against both adults and minors. Internally, the sentence is sustained by a host of legal and political justifications, which human rights activists denounce as vague and broad.

Vernon, a partner at US firm Lewis Brisbois Bisgaard & Smith, explains that ‘Saudi Arabia’s legal system is an ultra-conservative Wahhabi interpretation of the Islamic law. It doesn’t appear Saudi Arabia will sign the ICCPR in the near future.’

Almost three-quarters of those facing execution in Saudi Arabia were sentenced to death for non-violent offences, according to Reprieve. Already, Riyadh has put to death 48 people since the beginning of 2018, half of them for non-violent drug crimes. The country has carried out nearly 600 executions since 2014.

Like Iran, Saudi Arabia commits other rights violations, such as systematic discrimination against women, persecution of the Shiite minority and widespread torture. And there are indications that the situation could worsen. Last year, the ambitious Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman started a new wave of suppression of academics, journalists and independent Islamic scholars calling for ‘real’ political and business reform, a fact not lost on observers of rights conditions in the desert kingdom.

‘Executions in Saudi Arabia have doubled under Mohammed bin Salman. In the eight months after he was appointed Crown Prince (July 2017 – February 2018 inclusive) there were 133 executions in Saudi Arabia, compared with 67 in the eight months preceding (October 2016 – May 2017 inclusive),’ Foa explains. ‘If this rate continues (on average just over 16 per month), 2018 could see 200 executions, the highest number of executions ever recorded in Saudi Arabia in one year.’

It’s abuses like these that Tehran points to, to bring home double standards in the treatment of its own rights record. Javaid Rehman, UN Special Rapporteur on human rights in Iran and a member of the IBA Taskforce on International Terrorism, agrees that Saudi Arabia sometimes gets a pass, especially from Western governments, which Tehran does not enjoy. ‘There are clearly double standards on the part of the West,’ he says. ‘It tends to overlook worse regimes such as Saudi Arabia as they are allies – economic interests play a major role.’

Trouble in the neighbourhood

The Middle East, ruled mostly by autocrats, has been in the throes of a political upheaval, which has seen young people caught in brutal police crackdowns and military operations. While Iran and Saudi Arabia are seen as the top users of the death penalty, other countries in the region also employ the punishment. As repressed young people, who make up the majority of the population, show signs of restlessness and impatience, regimes are resorting more readily to heavy-handed methods to quash and pre-empt potential dissent, including the arrest, sentencing or possible execution of minors. There’s a fear that even more minors may be swept up in the overall march towards the penalty as instability continues to engulf the region.

IHR notes that Iran undertakes the most executions, followed by Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Jordan. ‘There has been a general increase in the use of the death penalty in the Middle East during the past few years. I believe this increase has to be seen in light of the political situation in the region,’ says Amiry-Moghaddam. ‘In Egypt, for example, the use of the death penalty has increased dramatically since 2013 and Jordan resumed implementation of the death penalty in 2014.’

In Egypt, Amnesty International says that in 2017 recorded death sentences increased by about 70 per cent compared with 2016, but there were no records of minors being targeted within the legal system over the past two years. The NGO didn’t include extra-judicial killings that may have targeted minors in the Sinai, where the Egyptian military is engaged in a lethal fight with sections of the local population, as well as with an affiliate of ISIS. However, in the rest of the Middle East, Amnesty International says the overall number of executing countries remains the same and that Bahrain, Jordan, Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates resumed executions after a respite.

Some countries like Iran and Saudi Arabia use religion [to justify the death penalty]; others use the fight against terrorism... The aim is to spread fear and keep political control

Mahmood Amiry-Moghaddam

Director, Iran Human Rights

‘It is essential to note that death sentences and executions against children are the exception in the Middle East,’ says Bracq. ‘I found reports of minors being sentenced in Egypt since 2014 but nothing in the last two years. Jordan does not allow the death penalty for juvenile offenders. Generally, the increase in the use of the death penalty in the country is related to the fight against terrorism – same in Iraq and Bahrain.’

What’s behind the increase?

More than 160 countries have barred the death penalty or do not practice it, according to the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Of those, 104 countries had completely barred the death penalty by the end of 2016. While globally there is clearly a move towards the abolition of the death penalty, that’s not the case in the Middle East.

The definition of children in Islamic sharia lies at the heart of why the penalty is not, like in many other countries, on the retreat, especially for minors. ‘The main reason behind the use of the death penalty against persons under 18 lies with the definition of “children”,’ says Bracq. ‘Under sharia law, the majority is reached at the age of maturity/puberty. The death penalty only applies to individuals who have reached the age of maturity under sharia law. In Iran, for example, the age of “maturity” is around nine years old for girls and 15 years old for boys.’

Bracq continues, ‘Whereas, in Saudi Arabia, the situation is a bit unclear. The maturity of the offender has not been codified and is established on a case-by-case basis by judges, based on several factors such as pubic hair or menstruation. Judges have the discretionary power to decide that a child has reached the age of maturity.’

Bracq says other countries are influenced by Islamic sharia. ‘Egypt’s criminal legislation finds its sources in sharia law. When a court sentences an individual to death sentence, the Grand Mufti must be consulted (to check its compliance with sharia law).’

While Islamic sharia can be pointed to for the resurgence of death penalty sentences in the region, political unrest, fear of public uprisings and increased insurgency are also culprits behind the current wave of death penalties.

It is essential to note that death sentences and executions against children are the exception in the Middle East

Natacha Bracq

Programme Lawyer, International Bar Association’s Human Rights Institute

Amiry-Moghaddam sees sharia as more of a pretext exploited by regimes towards political ends. In countries such as Egypt, Iran, Saudi Arabia and Sudan, capital punishment has been used to punish political opponents, sometimes including young people. ‘Countries like Iran and Saudi Arabia use the sharia age of criminal responsibility as an excuse to issue death sentences for juvenile offenders. However, when it comes to issuing a driving licence, they operate with the 18 years of age limit,’ he says.

‘I think the answer lies in the fact that the victims of the death penalty are the weakest members of society and juveniles are among them. Iran and Saudi Arabia use Islam and sharia as a means to control society and that’s the reason why these countries, which otherwise are very modern, seek to use sharia and choose 1,400-year-old punishment methods,’ Amiry-Moghaddam continues.

‘Countries using the death penalty use different excuses to justify this outdated and inhumane punishment. Some countries like Iran and Saudi Arabia use religion, others use the fight against terrorism as justification. The aim is to spread fear and keep political control.’

Rehman says different conditions offer fertile ground for the practice: ‘Juvenile justice is extremely poor in countries such as Iran, Jordan and Saudi Arabia – this is due to poor criminal justice mechanisms (a combination of customary norms and in some instances interpretations of the sharia law),’ he argues. ‘Even if sharia is not deployed directly, repression through dictatorial mechanisms is used to support death penalty.’

Looking ahead, legal experts say a range of factors need to be in place, first for better juvenile justice and for regimes in the Middle East finally to turn against capital punishment.

Vernon states that ‘if the US and the remainder of the world community are truly interested in abolishing the death penalty in these countries, the focus should be on enhanced education and tying the abolition to trade negotiations. It is not just minors at risk under these inhumane laws, consider those with mental health issues.’

Creating a public consensus against juvenile executions in Iran and elsewhere is another factor, argues Rehman, who recommends ‘greater awareness of the ineffectiveness of the death penalty in preventing serious crimes and educating societies about protection of minors’.

Amiry-Moghaddam sees international political pressure as the main tool. ‘Sustainable international pressure and supporting civil society in fighting to abolish the death penalty in those countries is what’s needed,’ he says. ‘Death penalty for juveniles should have political consequences. The international community must push for reform in the law and practice of the countries still implementing the death penalty for juveniles.’

Emad Mekay is the IBA’s Middle East Correspondent. He can be contacted at emekay@stanford.edu