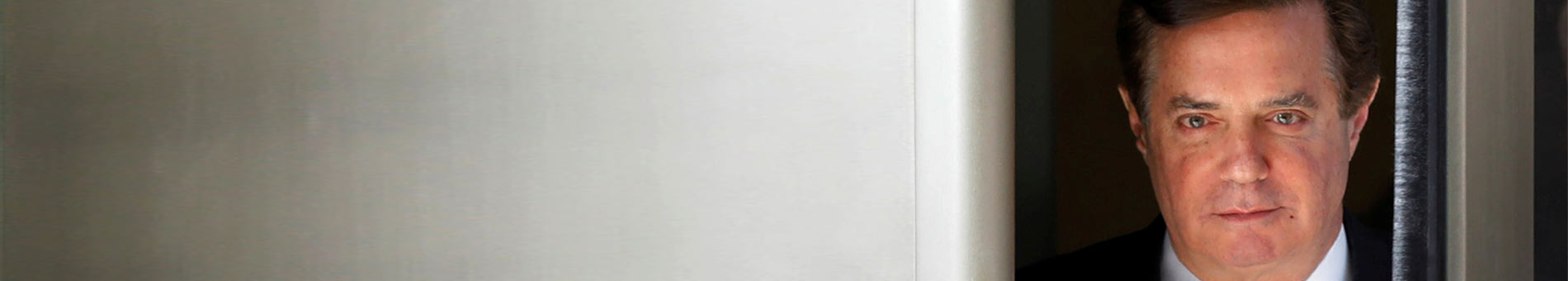

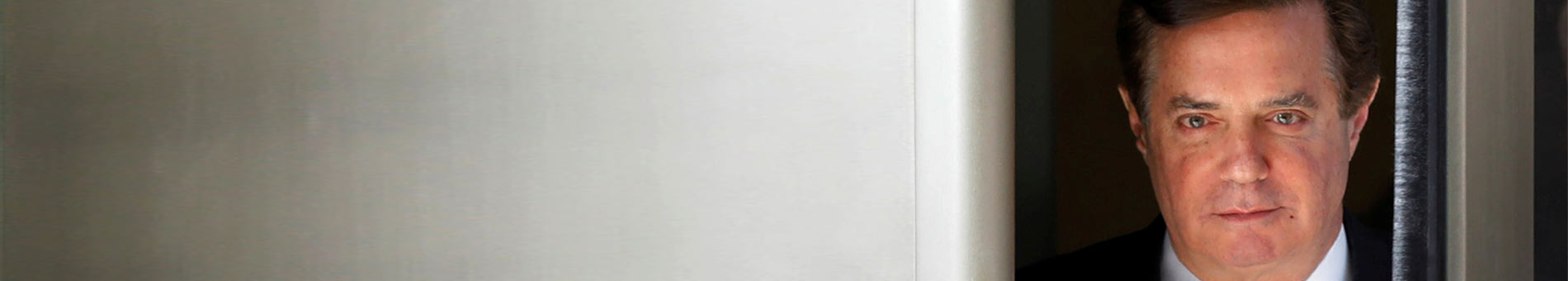

Trump’s Presidency: The trials of Paul Manafort

Michael Goldhaber, IBA US Correspondent

The lurid revelations have highlighted just how debased Western political and business culture have become. By tracking Paul Manafort’s trial and guilty plea, Global Insight highlights what needs to change, from abuse of shell companies to prosecuting kleptocrats.

Of the more than 30 defendants indicted by Special Counsel Robert Mueller, only Paul Manafort chose to stand trial. The trying of President Donald Trump’s former campaign chair therefore had the unique potential to crack open the Russia investigation for all the world to see. Prosecutors must often frame their case narrowly to maximise the odds of conviction, keeping the most telling facts from the jury. But, even at the surface, Manafort’s is a tale of greed on an epic scale.

Just beneath the surface lurks a tale of espionage for the ultimate geopolitical stakes. ‘In some ways it has nothing to do with Russia,’ says the former prosecutor Seth B Waxman. ‘In other ways it has everything to do with Russia.’ In perhaps the broadest possible perspective, says David Kramer, Assistant Secretary of State for Democracy under President George W Bush, Manafort’s story signifies ‘a failure of Western business and political culture’.

What the jury heard

Manafort’s trial, held during August in Northern Virginia, stuck to financial crimes. The prosecution introduced the Ukrainian politician Viktor Yanukovych as a ‘cash spigot’ who showered Manafort with money for electoral advice. While Yanukovych was in power from 2010 to 2014, Manafort hid from the United States Treasury Department 31 offshore bank accounts holding more than $60m and dodged income tax on $16.5m. Documents show that Manafort used his shell company accounts to buy three homes worth $7.75m in one year. He spent $400,000 landscaping a fourth home with a flowering ‘M’ decorated by a waterfall and became a top-five customer at the luxury men’s shop Alan Couture (wiring nearly $1m), where his taste ran to jeans made of cashmere and jackets made of ostrich or python skin.

Ostentation isn’t a crime, as the judge tartly noted, but the prosecutors sought to establish that Manafort was hooked on it. When Yanukovych left office, they argued, Manafort resorted to bank fraud because his cash spigot dried up and he needed to summon cash ‘out of thin air’. In or around 2016, Manafort repeatedly doctored his profit statements and vastly exaggerated his earnings in order to obtain four loans from three banks worth more than $20m. As the government summed up its case at closing: ‘Manafort lied to keep more money when he had it, and lied to get more money when he didn’t.’

Almost the only place where prosecutors couldn’t avoid alluding to the President was in the story of the two biggest loans. The Federal Savings Bank caters to low-income military veterans. After its Chief Executive Officer, Stephen Calk, expedited an initial $9.5m loan for Manafort over his executives’ objections, Calk was named an economic advisor to the Trump campaign. In November, Manafort pushed the then President-elect’s son-in-law Jared Kushner to have Calk appointed Secretary of the Army (fallbacks included ambassador to Australia, Britain, China, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Spain, the European Union and the United Nations). Kushner replied, ‘On it!’ But Calk received no job.

Throughout the trial, the defence tried to discredit Manafort’s right-hand man Rick Gates, who had pleaded guilty and served as the prosecution’s main guide to their many frauds. It so happens that Gates also oversaw President Trump’s inaugural festivities. During cross-examination, lead defence lawyer Kevin Downing asked Gates whether he had perhaps embezzled money from the inauguration. Gates dodged and Downing pressed. Finally, Gates admitted: ‘It’s possible.’ As a matter of trial technique, this was the most proficient punch of the bout. But at closing, lead prosecutor Greg Andres insisted that 399 exhibits were his star witness, and the jury seemed satisfied.

The defence’s other main strategy was to play on the false narrative, encouraged by President Trump, that the Mueller investigation is a witch hunt. Manafort failed to switch the venue to a Republican city in Southern Virginia, but he succeeded in avoiding a consolidated trial in Washington, DC (which voted 93 per cent for Hillary Clinton). He gambled, correctly, that a jury pool in purple Northern Virginia would include a few Fox News viewers.

‘Typical DoJ prosecutors’ don’t prosecute crimes like these, insinuated defence attorney Richard Westling. No one cared about Manafort ‘until the special counsel showed up and started asking questions’.

‘What would be the motivation [for going after him]?’ he asked the jurors at closing. ‘I’ll leave you to determine what was behind that.’

The prosecutors objected and the judge gave the jurors a curative instruction. But the damage was done. In Waxman’s view, ‘That comment in closing was the most inflammatory, improper thing the defence could have said.’

After four days of deliberation, on 21 August, the jury convicted Manafort of eight counts and failed to reach a verdict on ten others. The jury agreed that Manafort was guilty on all five charges of tax evasion, one charge of failing to file a Foreign Bank Account Report (FBAR), and two charges of bank fraud. But the jury could not reach agreement on the Federal Savings Bank loans or on the remaining FBAR counts.

Eleven of the 12 jurors saw Manafort as guilty beyond a shadow of a doubt on all charges, according to a juror who spoke to the media. The questions the jury sent the judge during deliberations shed light on the holdout’s reasoning. On the FBAR counts, the holdout seemed to mistakenly believe that Manafort could evade reporting foreign accounts held in the name of a shell company even if he controlled the disbursements for his own benefit. As to the Federal Savings Bank charges, the holdout appeared to believe that it couldn’t be fraud if the CEO approved the loans with eyes wide open (for his own dubious reasons), after Manafort’s lies had been exposed. In fact, federal bank fraud encompasses attempted fraud.

Astonishingly, one website contrived to run the headline, ‘Jury Fails to Convict Manafort on Majority of Counts’. But serious observers have been unanimous that the hung counts don’t matter. ‘It was absolutely a victory for the prosecution,’ says former US Attorney Barbara McQuade. When juries convict on only some charges, she says, ‘history remembers [those verdicts] as convictions’.

Even as a legal matter, the jury’s compromise would be of no consequence at sentencing, because a judge may count as relevant any conduct that’s been proved by a preponderance of the evidence. Ironically, the holdout juror’s only effect might be to allow a future state prosecution for the Federal Savings Bank fraud without triggering double jeopardy.

Based on the Virginia trial alone, McQuade estimated that Manafort faced a grim future for a 69-year-old who loves creature comforts. ‘Between six and ten years in a white collar case would be very significant,’ said McQuade, and the prosecutors weren’t nearly done with Manafort. The Virginia trial was ‘a complete victory for the government,’ concluded Waxman. ‘Total victory,’ agreed Harvard Law School professor Alex Whiting.

What the trial was really about

At the courthouse in Richmond, the government steered clear of Russia as much as it could. ‘The prosecution made a strategic choice to lower the bar for themselves by proving straightforward financial crimes,’ says Waxman. ‘Why should they out themselves and risk providing discovery into the entire Mueller investigation?’

But a larger game was afoot, and everyone knew it. ‘You don’t really care about Manafort’s bank fraud,’ said the Virginia Federal Judge

T S Ellis, (who was appointed by Ronald Reagan), as he addressed the prosecutors in a moment of pretrial frankness. ‘What you really care about is what information Manafort could give that would reflect on Trump and lead to his prosecution and impeachment.’

President Trump offered a similar take, but went considerably further. He impugned the legitimacy of the government’s approach – while perhaps sending a signal to the accused. The day after the Manafort verdict (and the simultaneous guilty plea of his lawyer Michael Cohen – see box: Michael Cohen: The second bombshell of the hour), the President told the hosts of Fox & Friends: ‘This whole thing [is] about flipping’ – and flipping ‘almost ought to be outlawed.’ That same day, the President praised Manafort on Twitter, because ‘unlike Michael Cohen, he refused to “break”… Such respect for a brave man!’

Many lawyers were aghast that the President was attacking the basic workings of criminal law. The Department of Justice (DoJ) charged Mueller with investigating serious potential crimes, and as Judge Ellis ruled, Mueller is well within his authority to follow the trail of other serious crimes (many of them now proven). Of course this case ‘was largely brought to flip Paul Manafort,’ Waxman retorts. ‘There’s nothing wrong with that. An individual who wants to accept responsibility for their guilt is something to encourage under any circumstances; we tell our children that. Sometimes the only way to get to the bottom of a conspiracy is to get someone inside it to explain how it operates.’

What [the prosecution] really care about is what information Manafort could give that would reflect on Trump and lead to his prosecution and impeachment

T S Ellis

Senior Judge, US District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia

Even more troubling, some lawyers believed that the President intended his comments to dangle a pardon before Manafort. ‘The President calls someone who flips a “rat”, and says that people who don’t flip are doing the right thing,’ says Waxman. ‘That juxtaposition is virtually the same as saying, “I’ll pardon you if you don’t testify against me.”’

Whiting agrees. ‘It could not be more clear,’ he says. ‘Trump’s tweets and statements since Manafort was convicted are designed to encourage Manafort to stay quiet and not cooperate, with the promise of being pardoned after. I think it is obstruction of justice. Dangling a pardon can certainly form part of a pattern of obstruction, and I think it does.’ Waxman, however, suggests Manafort was willing to roll the dice at trial because he knew Mueller would be willing to take his plea later.

The bigger picture

A trial that aimed only at public education, with less concern for legal strategy, could have told a very different story. Instead, it could have presented Manafort as a globalising agent of corruption in both politics and business, and as the potential linchpin to a case for collusion with Russia.

Manafort had a knack for pioneering unscrupulous political practices and then making them global. He made his name in 1980 as the man behind Reagan’s ‘Southern strategy’, stoking historical resentments by launching their campaign in a Mississippi town famous for the murder of civil rights activists. The following year, Manafort helped to shatter the taboo against political consultants hawking their influence with the politicians whom they got elected.

Trump’s tweets and statements since Manafort was convicted are designed to encourage Manafort to stay quiet and not cooperate, with the promise of being pardoned after. I think it is obstruction of justice

Professor Alex Whiting

Harvard Law School

‘This was a major change in the way Washington worked,’ recalls the campaign finance reformer Fred Wertheimer. ‘People who’d been involved in electing candidates now turned their relationships into cash.’ And where that cash came from was of no concern to Manafort’s firms. Over time their client list became a ‘who’s who’ of the world’s kleptocrats: Sani Abacha, Ferdinand Marcos, Daniel arap Moi, Teodoro Obiang Nguema, Jonas Savimbi and Mobutu Sese Seko.

If kleptocrats made great clients, why not service all their needs? Manafort’s next insight was that ruthless foreign politicians could use his dark arts not only in Washington, but also in their own capitals. Enter Yanukovych.

Yanukovych’s effort to steal the 2004 Ukrainian election ignited the Orange Revolution. Manafort brought Yanukovych back from the political wilderness by teaching him to dress better, and to play on the historical resentments of Russian speakers because it polled well. In effect, Reagan’s Southern strategy morphed into Ukraine’s Eastern strategy. As one trial witness put it, ‘Manafort brought American-style politics to Ukraine.’ After his 2010 election was certified as ‘free and fair’, Yanukovych returned much of the nation’s natural gas wealth to allied oligarchs. According to Ukraine’s current prosecutor general, Yanukovych looted about $40bn from the Treasury in less than four years, in a nation where $40bn is the government budget. In early 2014, the streets of Kiev rose up again. When his violent suppression of the Euromaidan protests failed, Yanukovych fled to Russia.

The connections were thick between the shady political-business elites of Russia and Ukraine, which very much included Manafort. The Associated Press has reported, for example, that in a 2005 memo Manafort pitched the Putin-friendly Russian aluminum baron Oleg Deripaska on a Western lobbying plan that ‘would greatly benefit the Putin government’. While Deripaska vociferously denies that any such plan came to fruition, he admits to a deep business relationship. In a 2008 lawsuit, Deripaska accused Manafort of absconding with $18.9m that Deripaska purportedly gave Manafort to invest in Ukrainian business opportunities. What the jury didn’t know is that this fearful debt was still hanging over Manafort’s head when he signed up to work gratis as Donald Trump’s campaign chair.

Mueller’s team did not share with the jury an astonishing correspondence between Manafort and his longtime Kiev office head, Konstantin Kilimnik. It was common knowledge that Kilimnik studied at a language school for Soviet spies. Mueller openly concluded (based on evidence shared under seal) that he was tied to Russian intelligence through the Trump campaign.

Within days of being named campaign strategist, Manafort asked Kilimnik to forward Deripaska press clips on his new position, and asked Kilimnik, ‘How do we use to make whole?’ He also offered to give Deripaska private briefings on the Trump campaign. Kilimnik later emailed that, after spending five hours with ‘the guy who gave you your biggest black caviar jar’, Kilimnik wished to meet with Manafort to pass on a message from the Russian oligarch that ‘has to do about the future of his country’ and ‘is quite interesting’. Kilimnik then flew to lunch with Manafort at the Grand Havana Room in New York City on 2 August 2016. Later that month, The New York Times exposed secret Yanukovych ledgers listing millions in cash payments to Manafort, and Manafort abruptly resigned from the Trump campaign.

To suggest what Manafort might have done or planned to do on behalf of Russian interests would be pure conjecture. But, it’s known that Manafort was present at the famous 9 June meeting in Trump Tower between members of the Trump campaign and Russian representatives who promised dirt on Hillary Clinton. It’s also widely acknowledged that the Republican National Convention in mid-July softened its support for defending Ukraine against Russia at the behest of the Trump campaign. Kilimnik reportedly took credit for the platform change in private boasts (though Kilimnik denied this report before fleeing from Kiev to Russia).

The jury knew none of this. It knew of Kilimnik as a ‘translator’, whereas Manafort called him ‘my Russian brain’, and Mueller – whose grand jury indicted Kilimnik in June on charges of witness tampering on behalf of Manafort – calls him a Russian spy. The jurors learned of Manafort’s ostrich jacket, but not the ostrich herd kept by Yanukovych at his Mobutu-style estate. Their heads have, so to speak, been buried in the sand.

Michael Cohen: The second bombshell of the hour

Paul Manafort’s jury conviction wasn’t the worst news for President Donald Trump on the afternoon of 21 August. Within minutes of that verdict, the President’s longtime personal lawyer Michael Cohen pleaded guilty in a Manhattan federal court to five counts of tax evasion – and to three counts arising from hush money payments Cohen made in 2016 to a pornographic actress and a Playboy model who each claim a romantic past with the President. Cohen confessed to making those payoffs ‘in coordination with and at the direction of’ (as he coyly put it) ‘a candidate for federal office’.

Cohen confessed to making an excessive campaign contribution by buying the silence of the actress known as Stormy Daniels for $130,000. He admittedly obtained that money through bank fraud by hiding $14m in debt on his application for an equity credit line. To silence the former Playboy bunny Karen McDougal, Cohen admittedly caused an unlawful corporate contribution, in enabling the purchase of her story rights by the publisher of the National Enquirer, American Media (which then quashed the story). Finally, Cohen pleaded guilty to hiding more than $4m in income from his taxi medallion business between 2012 and 2016. As part of his plea, he consented not to challenge any prison sentence between 46 and 63 months.

The President may at least be thankful that Cohen did not agree to cooperate with the Special Counsel investigation as part of his initial plea. Why Cohen hasn’t agreed to cooperate is a mystery to legal observers. ‘It’s incredibly unusual for a defendant to plead guilty to essentially what would have been the indictment without cooperating,’ says the former prosecutor Seth B Waxman.

Harvard Law School professor Alex Whiting suspects that Cohen would like a cooperation deal, but hasn’t satisfied the prosecutors. ‘Either Cohen hasn’t given useful information that they don’t already know from his documents,’ he conjectures, ‘or they think he hasn’t been truthful.’ Waxman speculates that Cohen wasn’t satisfied with the terms that the prosecutors have been offering, but he wished to make a good faith showing before the approach of the mid-term election (when the DoJ is loath to accept a plea in such a politically sensitive case). ‘I do think he will at some point cooperate,’ says Waxman. ‘I don’t think he has a choice.’

The leading precedent on sexual payoffs in presidential politics is that of Democratic candidate John Edwards. A jury failed to convict Edwards of campaign finance violations under similar circumstances in 2012.

On the verge of a second trial

In mid-September, Manafort stood at the threshold of a new trial in Washington, DC on charges of money laundering, foreign lobbying and witness tampering.

The second indictment accused Manafort of laundering millions from his offshore accounts into luxury purchases to enable the tax fraud on which he had already been convicted. And it accused him of laundering millions more through consultants who secretly acted as lobbyists for a foreign party in violation of the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA). By Waxman’s estimate, the total of over $30m in charged money laundering could have carried a sentence as hefty as 20 years.

The crux of the DC case was that the Brussels-based ‘European Centre for a Modern Ukraine’ acted as a front for Yanukovych and his governing party. Manafort was indicted for funnelling money from Yanukovych-allied oligarchs to Western lobbyists, who sought to persuade US officials that Yanukovych was elected fairly, had legitimate grounds for imprisoning his rival Yulia Tymoshenko, and was generally such a good pro-Western guy that the US shouldn’t slap economic sanctions on his government.

Manafort’s firm gave the lobbyists a signed statement that the European Centre was utterly independent of any foreign political interest. The European Centre was their nominal client – but as one lobbyist emailed another, ‘you’ve gotta see through the nonsense of that’.

The second trial would have established that Manafort did similar undisclosed lobbying himself and, even when he belatedly filed under FARA under the pressure of the investigation, he tried to cover up the fact that he lobbied within the US. Indeed, even while under indictment, Manafort allegedly tried to send messages to two European publicists – both directly and through his colleague Kilimnik – that they should deny any lobbying occurred within the US. That earned Manafort a new count for witness tampering, and the privilege of experiencing the remainder of the legal drama from prison without bail.

Most observers assumed Manafort was holding out for a pardon. But, on 14 September, Manafort reached a global plea deal with prosecutors on the eve of the second trial. Prosecutors dropped their new charges (and their right to retry the ten hung counts) in return for Manafort pleading guilty to two reduced charges. Specifically, Manafort pleaded guilty to a witness tampering conspiracy, and to a wide-ranging ‘conspiracy against the US’ that encompassed illegal foreign lobbying by himself and others. As part of the plea, Manafort admitted essentially all charged conduct, including his money laundering activities and the bank fraud on which the first jury failed to convict him. He agreed to surrender $46m in tainted assets.

Crucially, Manafort also agreed to cooperate. Indeed, Mueller’s team told the judge that Manafort had already proffered information and plans to testify at other proceedings. He has every incentive to testify fully and truthfully. For, although Manafort can receive up to ten years in prison under the plea deal, Mueller’s team may drastically slash his sentence in return for cooperation it deems ‘successful’.

A pardon is still possible, but experts think it unlikely. To pardon Manafort after he has admitted full guilt would make it harder for the President to maintain his innocence.

Manafort may have little to gain from clemency, because Mueller’s team designed the asset seizures to be ‘pardon proof’. And even if he’s released from federal prison, Manafort may still have to contend with state prosecutions. In fact, the New York Attorney General and the Manhattan District Attorney have reportedly opened investigations. Manafort’s plea would seem to make any case on state tax evasion, bank fraud or money laundering straightforward.

Finally, Manafort has already sung to Mueller. Of course, the public doesn’t yet know if his tune is familiar or if it hits surprising notes. Maybe Manafort will share how it transpired that the Republican platform on Ukraine changed. Maybe he will elucidate what the President knew about the June 2016 meeting with Russians in Trump Tower.

In response to the plea, the President’s lawyer Rudy Giuliani initially stated that ‘the President did nothing wrong – and Paul Manafort will tell the truth’. The amusing fact that Giuliani rescinded the second half of this statement may be taken as a sign that Manafort’s song is worth hearing.

What’s been learned so far?

For a generation after the Berlin Wall fell, the naïve belief prevailed that globalisation would mainly help to spread the best practices of Western corporate governance. In reality, the flow of norms was two-way – and it wasn’t benign. Manafort manifestly exported to the former Soviet Union (and elsewhere) the worst of US political practices. And he was only in the vanguard.

‘Manafort certainly deserves his share of blame,’ says Kramer. ‘But he had other players involved, and not just in America. You could describe it as a failure of Western culture… If you offer enough money, people are willing to do things they know they probably shouldn’t. These kinds of regimes pay top dollar for good advocacy. And it’s not unique to Ukraine. Look at Manafort’s previous client list. It’s all over the globe.’

The Manafort trial again shows how integral the US legal system is to facilitating global corruption

Mark Hays

Senior Advisor, Global Witness

The Democratic political consultant Tad Devine testified at the trial that ‘international lobbying is not a partisan endeavour’. As someone who left Yanukovych’s payroll to become chief strategist for Bernie Sanders in 2016, he ought to know. To complete the embarrassment of all three leading 2016 campaigns, Manafort also funnelled Ukrainian cash of dubious origin to the brother of Hillary Clinton’s campaign chair, the Democratic lobbyist Tony Podesta. To help sanitise Yanukovych, Manafort even recruited the former Obama White House Counsel Gregory Craig, then of Skadden, Arps, Slate Meagher & Flom. CNN, followed by other major news outlets, reported in August that Mueller has referred the foreign lobbying activities of Podesta and Craig for investigation in the Southern District of New York, along with those of the former Newt Gingrich lieutenant Vin Weber of Mercury Public Affairs. (No charges have been brought.) Meanwhile, on the other side of the Atlantic, Manafort found it just as easy to buy up members of the centre-left political establishment for an unacknowledged PR push. Among Manafort’s biggest purchases in Europe were the former Austrian Chancellor Alfred Gusenbauer and the EU’s first High Representative for Foreign Policy, Javier Solana.

In the other direction, perhaps Manafort may be said to have imported Russian-style business corruption to the US. Manafort’s longtime partner Rick Davis inadvertently put his finger on the biggest difference between the two cultures when he confessed: ‘We loved non-US business because the political and business elites are the same.’

To corruption activists like Mark Hays of Global Witness, the intermingling of kleptocrats and oligarchs is exactly what makes nations like Russia so vulnerable, and what makes the acceptance of their tainted cash by Western professionals so unacceptable. ‘If you’re serious about transparency,’ he says, ‘bright lines between the public and private sector are essential. When those lines aren’t there, individuals of all sorts can come in and exploit the infrastructure of state and set it up as a looting mechanism.’ Just ask Ukraine’s prosecutor general.

At the trial, Judge Ellis intriguingly asked the prosecution to stop using the term ‘oligarch’, because ‘if oligarch just refers to a billionaire involved in politics, then both Soros and the Koch brothers would qualify’.

Wertheimer, the US political reformer, takes Ellis’s point – but he’d apply the term to both sets of tycoons rather than neither. ‘An oligarchy is a small group of wealthy individuals influencing the government process,’ he says. ‘I use oligarchs to describe billionaires in this country. I don’t see any problem using it.’

By contrast, the Russian expert Kramer sees a meaningful distinction. Ukrainian oligarchs, he says, ‘are not the same as Koch and Soros. Whether you like what they do or not, they at least abide by the rule of law. The other guys don’t.’ In that sense, Manafort would seem to be more of a Ukrainian-style oligarch.

Kramer is comfortable calling Manafort an importer of corruption in the sense that he’s accused of laundering dirty Ukrainian cash, but he emphasises the West’s culpability. ‘I’ve often said Putin’s most successful export is corruption,’ he says. ‘But exports from Russia require importers in the West, and that’s a failure on our part. We don’t live up to our standards when we demonstrate that we have a pricetag. Corruption and kleptocracy can only work so far within the borders of these repressive regimes. They benefit by being able to exploit Western financial systems, and by buying Western real estate.’

Hays agrees: ‘The Manafort trial again shows how integral the US legal system is to facilitating global corruption.’ Kramer endorses the renewal of targeted economic sanctions by the West on corrupt oligarchs, accompanied by a new US commitment to transparency for shell companies and increased prosecution of kleptocrats for laundering their ill-gotten gains in the West.

As to the suggestion that Manafort’s misdeeds smack of Russian business culture, all the experts pull up short. ‘I don’t know if I’d compare what he did to what I saw in the Ukraine,’ says Kramer. ‘Ukraine has its troubles and it’s trying to clean itself up in fits and starts. Manafort is a stain on us. Tax evasion and bank fraud and selling government positions are not right in any country, and it certainly shouldn’t be right in this country.’

Hays sees peddling a government post to a bank CEO as American-style ‘pay-to-play politics’, and he worries that recent Supreme Court decisions have made ‘quid pro quo bribery’ harder to prosecute. Wertheimer thinks that particular scheme is atypical, because the US traditionally has strong rules to prevent the use of public office for private gain, but he makes a broadly similar argument.

‘We didn’t need Manafort to bring corruption problems to this country,’ says Wertheimer. ‘Our corruption occurs mainly through the campaign finance system. We’ve had campaign finance problems, we’ve fixed them, and we need to fix them again.’

Citing the Manafort case, the Democratic presidential hopeful Senator Elizabeth Warren calls for an outright ban on lobbying US officials on behalf of foreign nations as part of her Anti-corruption and Public Integrity Act. But Wertheimer worries that a ban wouldn’t survive a First Amendment challenge. He’d prefer to see the lobbying disclosure rules of the FARA tightened. ‘The key to all of this may be figuring out how to strengthen FARA,’ he says. Think tanks like Public Citizen are working on it, but pending reform bills have gone nowhere. Seeing the mischief wrought by Manafort in Ukraine itself, Hays urges Congress to explore disclosure rules for what US political consultants do abroad.

London, UK, 13 July 2018: A banner, critical of Donald Trump, displayed during a protest march against the President’s visit to the UK.

Everyone (including the DoJ) agrees that starting to take the existing FARA rules seriously is essential – and that was the main point of the second Manafort indictment. The prosecution has sent a loud and salutary message to lobbyists for foreign interests in DC. But Hays would like to remind Mueller’s team that the main victim of the saga is Ukraine, which Manafort helped to pillage and plunge into civil strife. While Manafort’s real estate collection may not be in Yanukovych’s league, it surely surpasses the imagination of anyone who entered political consulting before Manafort began to progressively monetise the profession. What the DoJ plans to do with the $46m surrendered by Manafort is not yet known.

‘I’d like to see the US government return the proceeds to Ukraine or dedicate it to a broader asset recovery effort,’ says Hays.

‘It’s the least the US government should do.’

Michael Goldhaber is the IBA’s US Correspondent. He can be contacted at michael.goldhaber@int-bar.org