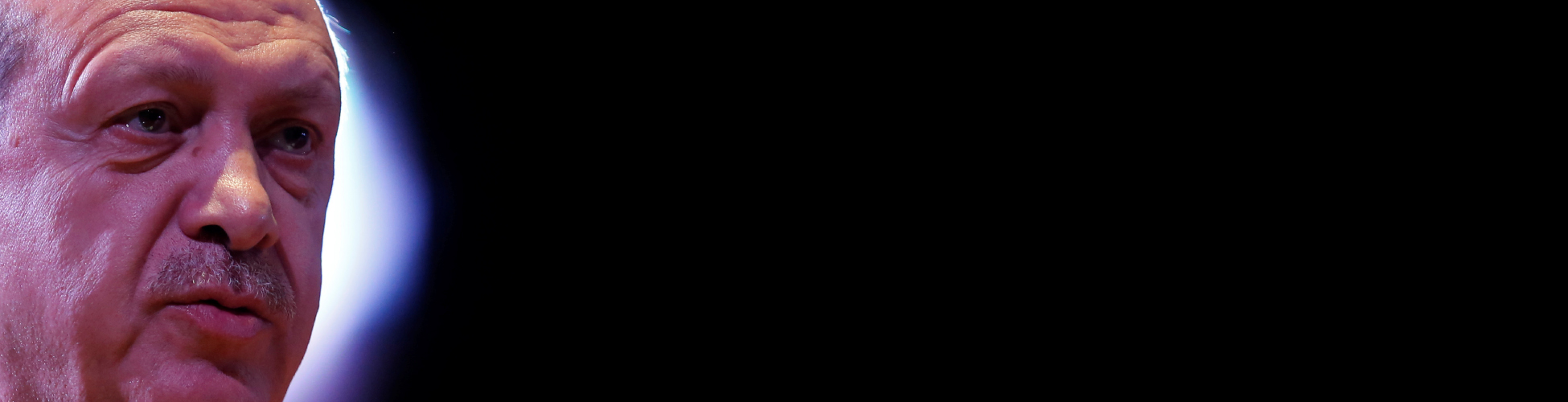

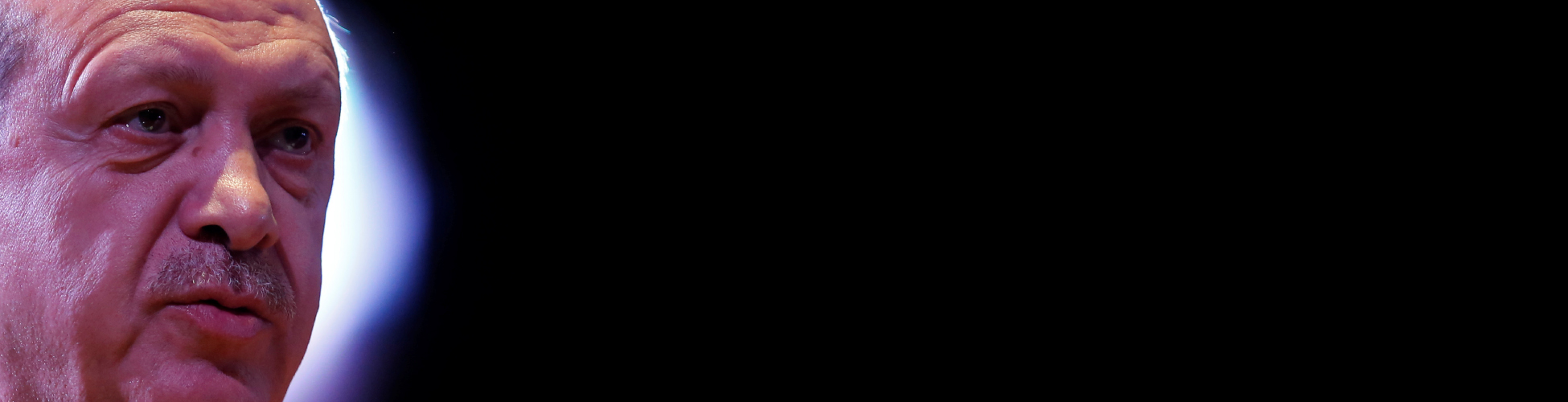

President Erdogan's 'new Turkey'

Lorena Rios

Following the country’s recent referendum, the President has sweeping new powers. Global Insight speaks to lawyers and legislators about proposed constitutional amendments, and the impact centralised executive power could have on Turkey’s rule of law.

On 16 April, Turkey voted in a monumental referendum in which the course of the young nation’s history came down to one choice: yes or no.

The people of Turkey voted in favour of a constitutional reform package that will replace the country’s parliamentary system of governance with an executive presidency. The reform was pushed forward by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his ruling party, the Justice and Development Party (AKP), despite critics’ claims that the reform is a pathway to authoritarianism and an attempt on Erdogan’s part to legalise the de-facto powers he has assumed since last year’s failed military coup.

The reform package passed by a tight margin: 51 per cent voted for and 49 per cent voted against, according to Turkey’s Supreme Election Council (YSK). The result is testament to a polarised Turkish society and divisive politics. Turkish people didn’t only vote for or against Erdogan, the most influential leader since Turkey’s founding father Mustafa Kemal Atatürk –who served as the country’s first President from 1923 until his death in 1938 – they voted for what they conceive to be the future of Turkey. It was the nation’s values at stake that night, which resulted in an astounding 85 per cent voter turnout.

As a result, the President now has the power to issue decrees, declare emergency rule, appoint ministers and top state officials, and dissolve Parliament.

Democracy or power grab?

President Erdogan’s desire to leave the final decision up to the nation’s will is a display of his proud commitment to democracy, which he uses in defence of those who accuse him of blatant power grabbing. It is worth noting that Erdogan has a wide support base as well as the charisma that allows him to stir nationalist sentiment amidst a deteriorating security situation and a contracting economy.

The controversial reform bill is comprised of 18 article amendments approved by Parliament after brawls and fist fights. Erdogan insisted on giving Turkish citizens the final say through a referendum. In the months prior, the AKP, in coalition with the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), launched the ‘yes’ campaign while the pro-Kurdish and secular opposition parties led the ‘no’ campaign.

‘The parliament said “yes” for this and now the nation is saying “yes”,’ said President Erdogan in a speech on 3 February. The new system of governance will come into effect in November 2019. ‘God willing, these results will be the beginning of a new era in our country,’ he said at a news conference on the Sunday night following the results announcement.

In Istanbul, the results were met with both celebrations and protests in different parts of the city. Despite winning by about 1.3 million ballots, Erdogan lost in the country’s three largest cities: Ankara Istanbul and Izmir. The outcome of the referendum was plagued with irregularities, as the state press and Erdogan announced the results before the YSK. The main opposition parties declared the election a fraud and are demanding a recount of at least 37 per cent of the votes. The High Electoral Board had announced it would not accept ballots that were missing ballot commission stamps. The opposition’s visceral reaction and ‘no’ campaigners’ anger is a result of the Board reversing their decision after voting was already underway, saying it would accept unstamped ballots ‘unless they are proven to have been brought from outside’.

Abdulrrahman Atalay, a software developer and member of the opposition movement that sprang up after the anti-government Gezi Park protest of 2013, led the ‘no’ campaign in the municipality of Beyoglu in the heart of Istanbul.

‘The “yes” won, but under what conditions?’ he asks rhetorically. ‘All national media called us terrorists. All media campaigned for the “yes” camp. Every day they blamed people.’ ‘No’ campaigners claim they have faced intimidation and threats of violence, while independent monitors say state media slanted coverage in favour of the President.

Deputy Prime Minister Numan Kurtulmus claimed that a ‘yes’ result in the referendum means supporting a more effective fight against terror. Since the bill was approved, the government’s ruling party, supporters and pro-government media have equated the ‘no’ campaign with terrorism and warned that a ‘no’ vote would lead to civil war. ‘Who are the ones saying “no”?’ continued President Erdogan. ‘Those who want to break up the country. Those who are opposed to our flag.’

‘We felt insecure during the campaign,’ says Atalay, who was detained by the authorities for three days for attending one of the protests that sprung up in the city after the elections. ‘People with different political views came together under the “no” campaign, but we didn’t criticise each other,’ he says. ‘Each group had their reasons to say “no”, but we all agreed on one very basic point: “no” to one man’s rule.’

Head of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights, Tana de Zulueta, delivered a report of the referendum, saying that the ‘no’ campaign had been restricted and suffered intimidation, and that media coverage had favoured the ‘yes’ camp. The decision not to count unstamped ballots was meant to avoid ‘ballot-stuffing’, where extra votes are cast illegally to manipulate results. However, the OSCE claims the electoral authority unfairly changed the rules after polls had opened.

A state without independence

A major concern this reform package prompts in Turkey and abroad is the changes in the structure of the High Council of Judges and Public Prosecutors (HSYK), as well as the independence of the judiciary. The new constitution would allow the President to appoint five out of the 13 members of the HSYK. The rest will be selected through parliamentary majority.

The restructured HSYK will have 13 members – down from 22 at present – four of whom will be selected by the President and seven by Parliament on this occasion. In practice, however, the President is, in fact, appointing six members, since he also has the right to handpick his ministers under the revised system. The minister of justice and the minister’s deputy join the cohort of 13 members, raising the number of members directly selected by the President.

The European Court of Human Rights uses four criteria to define the independence of the judiciary: the manner of appointment, term of office, existence of guarantees against outside pressures and appearance of independence. Under this amendment, none of these criteria are fulfilled and without an independent judiciary, there is no fair trial for anyone and no rule of law.

Following the military coup attempt of 15 July 2016, Turkey’s HSYK suspended more than 2,745 judges on suspicion of being sympathisers of Fethullah Gülen, the Muslim cleric believed to have orchestrated the coup attempt. As a result, the European Network of Councils for the Judiciary declared the HSYK an institution that was no longer independent of the executive and legislature ‘ensuring the final responsibility for the support of the judiciary in the independent delivery of justice’.

The International Bar Association’s Human Rights Institute’s (IBAHRI) Co-Chairs condemned the sudden dismissal of judges and prosecutors, outlining Turkey’s disregard for international law standards. ‘Protecting the independence and impartiality of the judiciary is crucial to ensuring the protection of Turkish citizens,’ added IBAHRI Co-Chair Baroness Helena Kennedy.

Sule Ozsoy, Constitutional Law Professor at Istanbul’s Galatasaray University, asks: ‘How fair is it to expect judges to try or examine the decrees of men to whom they owe their position?’

Mehmet Durakoglu, President of the Istanbul Bar Association, believes that the independence of the judiciary could be achieved within the limits of the parliamentary system. Under the current constitution, the President appoints the majority of the constitutional court.

However, the amendments don’t address this problem. Instead, they reduce the court members from 17 to 15, of which 12 are appointed by the President. ‘In short, the President may shape all the high courts and the Council which control all courts – high and lower,’ concludes Ozsoy.

A state of emergency

Article 12 of the reform states that the President would have the power to declare and issue state of emergency decrees outside of judicial control. It is worth noting, however, that Turkey has been under a state of emergency since the military coup attempt of July 2016. The proposed amendments and the campaigns leading to the referendum unfolded under the curtailment of civil liberties, the jailing of over 130 journalists, and the government’s decision to shut down dozens of media outlets. Over the past months, the state has targeted individuals through their social media accounts for being critical of Erdogan. Many are under investigation and face charges of insulting the President or spreading terrorist propaganda under Turkey’s anti-terror laws.

‘First of all, in democracies, constitutional changes are not made under emergency rules curbing free speech and political participation,’ says Ozsoy. Emergency decrees issued by the government can’t be examined by the judiciary according to the constitution. ‘Without judicial examination, there is no rule of law,’ she continues. ‘Currently, Turkey is already a competitive authoritarian system. There is no free and fair competition among parties.’

Protecting the independence and impartiality of the judiciary is crucial to ensuring the protection of Turkish citizens

Baroness Helena Kennedy

Co-Chair, IBA Human Rights Institute

The history that led to this controversial reform package is inherently intertwined with the rise to power of President Erdogan, one of the most prominent political figures in Turkish modern history. He founded the AKP in 2001, which has held the majority in Parliament since Erdogan became Prime Minister in 2002.

‘Turkey is going through a period where there is only one governing political party,’ says Durakoglu. ‘This takes place within the limits of constitutional law, but sometimes political powers have great influence over the judicial and legislative branches, as is the case now,’ he states.

In 2007, Erdogan’s presidential ambitions came a step closer to fruition when a constitutional reform package changed the role of the President from a ceremonial one to a directly-elected presidency. Erdogan was elected President in 2014, winning more than 50 per cent of the popular vote. Since then, Erdogan has advocated for a ‘Turkish style’ presidential system, but failed to meet the 330-vote threshold for it to pass. This time, however, the AKP, which holds 316 seats in Parliament, proposed the amendments and was able to pass the thresholds to make it to a referendum, with the support of the MHP, which holds 39 seats.

Ozsoy explains that, in the proposed presidential system, the President will have the authority to regulate all administrative law by decrees. ‘He can create government institutions or shut them down, appoint all bureaucrats or fire them, and regulate the rules binding government institutions.’

Under the reform bill, the powers of Parliament also diminish, as it loses its power to scrutinise ministers and cabinet members. Under the proposed constitution, the government will be voted in by popular vote, not by Parliament. ‘There will be no need for a vote of confidence or motion of censure against ministers,’ Ozsoy says.

First of all, in democracies, constitutional changes are not made under emergency rules curbing free speech and political participation

Sule Ozsoy

Constitutional Law Professor, Galatasaray University

The President will also be given the power to issue decrees having the force of legislation and hold the power of dissolution, veto and legislative decree. Furthermore, ‘the new constitution gives the President the power to dissolve Parliament without prior conditions attached, as well as other powers, as if it makes the current state of emergency permanent rather than temporary,’ adds Ozsoy. ‘It is obvious that this is not a democratic pluralistic plan – it can only support a competitive authoritarian system. There is no free and fair competition among parties.’

Turkey has one of the highest electoral thresholds in the world, which requires a party to win at least ten per cent of the national vote to enter Parliament. This limitation has not been addressed by the current amendments, making it very difficult for independent or opposition voices to be represented in Parliament.

The pro-Kurdish opposition party, the People’s Democratic Party (HDP), has been especially hit by the pressure imposed by the state since the conflict in Turkey’s southeast. Last November, HDP party leaders Selahattin Demirtas and Figen Yuksekdag were detained along with ten other members of Parliament from the same party. The HDP is linked by the state with terrorist activity carried out by the Kurdistan Workers’ Party and is often accused of carrying out terrorist propaganda or being a member of a terrorist organisation. Demirtas and Yuksekdag are still in prison.

‘The constitutional reform will result in a transformation to the dual party system,’ claimed HDP Spokesperson Ayhan Bilgen in February. He has also been detained. ‘The MHP will be incorporated into the AKP and the [Republican People’s Party (CHP)] will try to melt all parties into its own,’ he continued. ‘But we think this amendment will change the system into the one-party system, so the HDP will try to hinder this amendment by saying “no”.’

Different factions believe the proposed amendments to be an insufficient solution to amend a beleaguered system of governance. Even had there been a ‘no’ vote, Turkey would face a tough political environment to govern. Polarisation is a large obstacle among statesmen and segments of civil society. ‘Everyone acknowledges that Turkey doesn’t have a fully democratic system now,’ says CHP Deputy Chairman Bulent Tezcan. ‘But the reform package is more undemocratic. If it doesn’t pass, we want to emphasise legal reforms that strengthen legislative forces like Parliament, the empowering of the judicial system, restricting the power of the President, and separation of powers.’

Turkish President Tayyip Erdogan addresses his supporters during a rally in Izmir, Turkey, April 2017.

The proposed amendments would also result in holding parliamentary elections and the presidential election on the same day every five years. According to Sera Kadigil, a lawyer for the CHP, ‘this system is not logical for the political system in Turkey because people vote for a leader or a party’. The proposed changes don’t require the President-elect to terminate their party membership if they have one.

‘The President’s party will automatically become the majority in Parliament,’ adds Kadigil, which makes it harder for Parliament to indict the President. The proposed amendment states that Parliament can indict the President through a majority vote in the Grand National Assembly (the ‘Assembly’). The Assembly, in turn, will be able to prosecute the President through a secret ballot. The Assembly will be able to send the President to the Supreme Criminal Tribunal with the votes of two-thirds of its total number of members. However, as a leader of a political party, the proposed amendments also allow the President to appoint the majority of members of the Constitutional Court, which supervises compatibility of laws, decrees having the force of law and bylaws of the Assembly.

The reform bill offers a few positive amendments, such as Article 2, which increases the number of seats in the Assembly from 550 to 600, and Article 3, which lowers the age requirement to stand as a candidate in an election from 25 to 18. The rest have become the source of heated debate and organising from both the government and civil society.

President Erdogan says the constitutional reform will result in stability at a time of turmoil, and prevent a return to the fragile coalitions of the past. ‘Those who say “no” are on the side of 15 July,’ he said in a speech given in the eastern city of Kahramanmaras as part of his campaign.

‘In a true democracy, you need to have a constructive opposition that can take over if necessary,’ advises Hans Corell, Co-Chair of the IBAHRI. ‘It is important that there are shifts and balance in the society and, above all, that there is freedom of expression and freedom of the press,’ he says. ‘There has to be a dialogue.’

Kadigil was vocal about the negative impacts of the reform, appearing on television and actively rallying behind the ‘no’ campaign. ‘We need to free the media, Erdogan has to obey the current constitution and we need to cancel the state of emergency,’ she says. The right of citizens to be informed is threatened by the current state of emergency and the government’s crackdown on media outlets that are deemed by the state as dangerous and too critical. ‘We have a constitution, but only as a book on the shelf; we are not using it and they don’t let us use it.’

Abdulrrahman Atalay reflects on the future of Turkey – or the ‘New Turkey’, as Erodgan calls it – under a ‘yes’ rule. He is still hopeful. ‘We were successful,’ he says of the ‘no’ campaign. ‘There is no doubt that people will continue to organise and build a front against Erdogan in the 2019 presidential elections.’

Lorena Riosis a freelance journalist and can be contacted at riostlorena@gmail.com