Can the steel game be played fairly?

The ‘dumping’ of cheap steel from China into global markets continues to cause economic damage. With the Chinese government struggling to address steel overcapacity amid domestic tensions, other nations must take action.

Stephen Mulrenan

It’s tough times for the steel industry in many countries at the moment. The UK has been hit particularly hard. At the end of March, Tata Steel announced its intention to sell its entire loss-making UK business. As Global Insight went to press, more than 15,000 jobs – including 4,000 at Port Talbot, the country’s largest steelworks – were at risk, and the government had offered support to help secure a purchase. This follows the shedding of nearly 2,000 positions by the company across the UK last year.

Tata is by no means the only player in the steel industry facing difficulties. In October 2015, Thai steel producer SSI closed its works in Redcar, northeast England, resulting in 2,200 redundancies, while parts of Caparo Industries’ steel operations went into administration, bringing further closures and job losses.

UK steelmakers have blamed high energy costs, green taxes and the strong pound, saying that, compared to foreign competitors, the cost of making steel in the UK is too high.

The principal competitor they are most concerned about is China, whose booming steel industry now accounts for more than half of global output, or more than twice the combined output of the next four largest steel makers: Japan, India, the United States and Russia.

At the end of February, the Governor of Minnesota, Mark Drayton, in Washington, DC for a National Governors’ Association conference, asked President Obama whether there was any way ‘to prevent China from doing what it is doing’ – namely, selling its steel to global markets at low prices.

Obama has promised to address this so-called dumping of cheap Chinese steel, which has contributed to the loss of 12,000 jobs in the US industry, including 2,000 in Minnesota. Responding directly to Drayton, he said: ‘What is possible is making sure everyone is playing on a level playing field, and that people are operating fairly. And, frankly, I don’t think it is any secret that China in the past has not acted fairly.’

Domestic situation

The reasons for China’s actions are complicated. Demand for steel worldwide fell by 1.7 per cent in 2015 and is expected to rise by only 0.7 per cent in 2016. Global steel prices have fallen sharply and China’s own economic slowdown has led many Chinese producers to seek export markets due to falling domestic demand.

Akira Kawamura, Past President of the IBA and a partner at Anderson Mori & Tomotsune, says that, given the depressed nature of the steel market, the world should not be too surprised at what has happened. ‘It was not unpredictable that Chinese steel producers would introduce price dumping strategies to keep market share in the international market.’

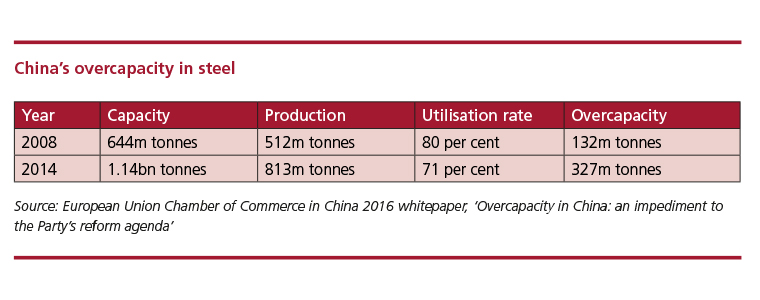

But, in addition to the damaging effect on the global economy, overcapacity in China’s steel industry – as well as in many other sectors – has also severely hampered the country’s own economic growth.

The European Union Chamber of Commerce in China has cited three main reasons why the Chinese government’s attempts to address overcapacity have not been successful: local protectionism; the threat of social unrest; and the government’s current role in the Chinese economy.

" It was not unpredictable that Chinese steel producers would introduce price dumping strategies to keep market share in the international market

Akira Kawamura

IBA Past President

Chinese state-owned steel mills have long viewed long-term market viability as less important than safeguarding the jobs and economic growth these projects deliver to local communities, according to the European Chamber. Local governments are therefore inclined to act in their own interests, says Caroline Berube, Senior Vice-Chair of the IBA Asia Pacific Regional Forum and a partner at HJM Asia Law & Co in Shanghai. ‘Steel enterprises are important to local governments, especially with regards to the issues of tax revenue and employment,’ she adds.

According to statements by the State Council, China aims to cut steel production capacity by 100 to 150 million tonnes. But how realistic is this?

In September 2015, China experienced its own job losses in the industry, when its largest northeast coal mining business, Heilongjiang Longmay Mining Holding Group, laid off 100,000 workers – 40 per cent of its entire workforce.

With many factories running out of money and construction projects being put on hold across China, many in the country are concerned that what occurred at Longmay Group may just be the ‘tip of the iceberg’ and that potential mass layoffs could enflame an already unsettled employment situation. For example, according to Hong Kong-based NGO China Labour Bulletin, the number of worker strikes in China surged to over 2,700 in 2015, more than double the previous year’s total.

Given the inflexibilities of the country’s social welfare system, the Chinese government is motivated to keep as many employees on the payroll as possible and avoid any actions that might stir up social unrest. ‘The Chinese government has even cut the export tariffs to encourage the steel enterprises to export steel to the international market,’ says Berube. As a result, there is considerable scepticism internationally that China will follow through on its production curtailment goals.

Global governments

A 2016 white paper on overcapacity in China, issued by the European Chamber, is intended to, in its own words, ‘inspire the Chinese authorities to vigorously pursue the necessary structural changes to reduce overcapacity and drive China’s economy to a new level of sustainable growth’. The European Chamber has put forward various recommendations it hopes will sharpen the aims and objectives of the 13th Five-Year Plan for economic and social development, and the success of China’s 2016 presidency of the G20.

" Governments should also change related policies to reduce production costs and enhance the competitiveness of their own steel enterprises

Caroline Berube

IBA Asia Pacific Regional Forum

‘For China, low price exports have not exactly made the businesses of steel enterprises better, with nearly half of medium-sized steel enterprises suffering business losses in 2015,’ explains Berube. ‘The Chinese government should guide these enterprises to reduce their production capacity, provide less government support, and let the market select the survivors.’

But if the efforts of the Chinese government come to nothing, as many expect, what measures can the governments of those countries adversely affected by the dumping of cheap Chinese steel take to protect their industries?

‘If there is no political pressure from the unemployment rate and demonstrations from steelworkers, governments may not want to aggressively enforce existing trade laws,’ says Berube. ‘This is because of the low price of steel from China which, as we all know, is beneficial for economic development.’

Growing trade tensions did lead the EU to impose anti-dumping duties for six months last year on some steel imports from China and Taiwan. In November 2015, according to the European Chamber, Member States also called on the EU to utilise ‘the full range’ of its trade defence instruments to support Europe’s steel industry, and many expressed opposition to China being granted ‘market economy status’ with the World Trade Organization.

Growing trade tensions did lead the EU to impose anti-dumping duties for six months last year on some steel imports from China and Taiwan. In November 2015, according to the European Chamber, Member States also called on the EU to utilise ‘the full range’ of its trade defence instruments to support Europe’s steel industry, and many expressed opposition to China being granted ‘market economy status’ with the World Trade Organization.

Kawamura says: ‘Large dumping cases, such as the one in the steel industry, are often a political or diplomatic question, and therefore a political or diplomatic judgement by an affected government is unavoidable.’

The US Congress, meanwhile, intends to pursue an alternative strategy. In February, it passed trade-related legislation that will give the President more tools to stop dumping, boost funding and increase resources.

But many argue that global governments need to do more to ensure the long-term development of their own steel industries, rather than simply relying on trade protection policy to reduce domestic unemployment. ‘They should also change related policies on energy, environmental protection, taxation and labour costs to reduce production costs and enhance the competitiveness of their own steel enterprises,’ adds Berube.

There is recognition within China that it cannot forever sustain an export-driven growth model and it may be that proposed initiatives by other governments under pressure will have their desired effect.

Stephen Mulrenanis managing editor of Compliance Insider at Compliance Publishing Group. He can be contacted at stephen.mulrenan@complianceinsider.com