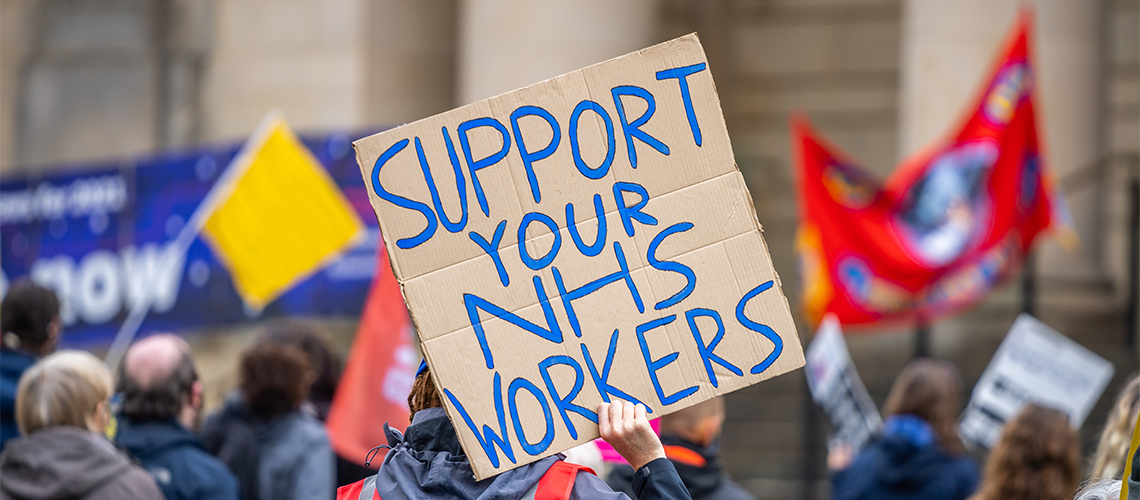

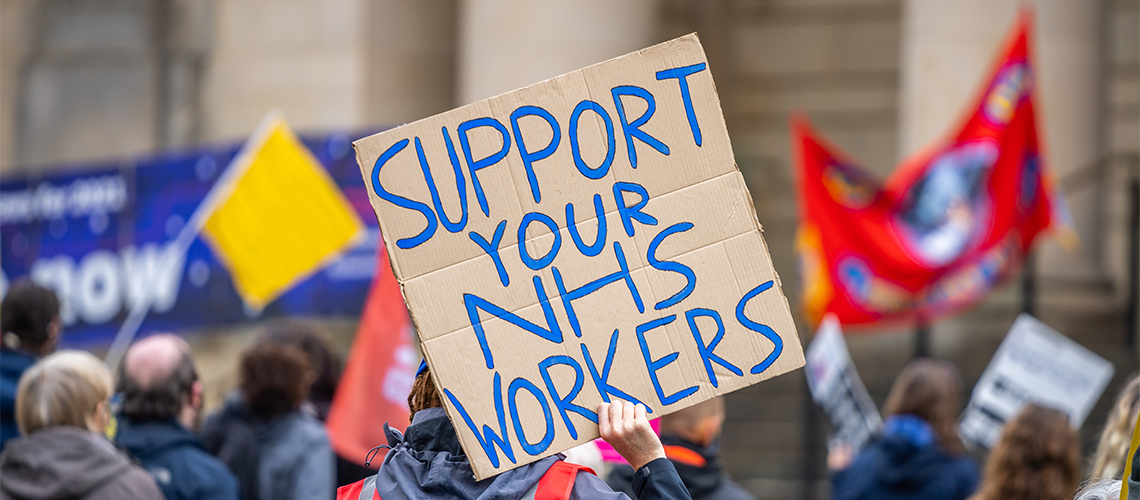

Employment: UK’s anti-strike proposals draw widespread ire

Joanne HarrisMonday 13 February 2023

It’s not quite the ‘winter of discontent’, which the UK suffered through in 1978 and 1979 – but the current widespread strike action by an increasing number of public sector workers is certainly causing disruption.

Last autumn, when transport unions began industrial action, the UK government introduced a bill into Parliament designed to enforce a ‘minimum service level’ in the sector. ad its first reading in October but was then quietly put on the back-burner; in its place, the Strikes (Minimum Service Levels) Bill was introduced in January.

This legislative proposal would grant ministers the power to introduce regulations requiring a minimum service level in key sectors: health; fire and rescue; education; transport; the decommissioning of nuclear installations and management of radioactive waste and spent fuel; and border security. After these regulations come into force, they’d apply to any strike taking place from that point.

Under the proposals, employers would give unions a work notice – subject to consultation with the union – identifying employees who are required to work during a strike, regardless of whether they’re union members. Unions won’t be protected under tort law if they fail to take ‘reasonable steps’ to ensure all identified employees comply with the notice. The Bill also removes the protection against unfair dismissal that currently applies to employees who take part in a strike; employers would be able to fire any identified employee who went on strike instead of working.

As one, unions have come out against the proposals. UNISON called the Bill ‘a full-frontal attack on working people’, while the British Medical Association said it ‘diminishes unions’ rights and responsibilities to represent their workers, infringes workers’ rights to strike and threatens key public sector workers with losing their jobs if they fight for better conditions’. Trades Union Congress General Secretary Paul Nowak said the legislation would ‘likely poison industrial relations and exacerbate disputes’.

There’s always been the argument that a good old-fashioned strike for a limited period serves both parties more than other avenues

Ed Mills

Senior Newsletter Editor, IBA Employment and Industrial Relations Law Committee

Lawyers representing trade unions are also concerned. Neil Todd, a partner in Thompsons Solicitors’ Trade Union Group, says the ‘authoritarian’ nature of the legislation, and the ‘sweeping powers’ it would give ministers, was the biggest worry. It’s also currently unclear what a relevant minimum service level or what reasonable steps unions will have to take to ensure that level will be, adds Todd, as this will be determined in subsequent regulations. ‘It’s a very difficult exercise to be able to establish what’s appropriate in any given area’, he says.

The UK’s Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy did not respond to Global insight’s request for comment.

Ed Mills, Senior Newsletter Editor of the IBA Employment and Industrial Relations Law Committee and a partner at Travers Smith, says the legislation wouldn’t prevent employees from striking, and was in some ways codifying existing practice. ‘Those working in important public services feel a tremendous tension about the impact on the public and particularly in those critical health and ambulance and fire services, that lives may be lost. Most people who vote to go on strike would feel that they need a minimum level of service’, Mills believes.

However, Mills shares Todd’s concerns about the government’s approach to this codification process. ‘Even if it’s right that you need a bit more process around it, this seems very one-sided from the government. It’s essentially a blanket power to set minimum services in regulations’, he says.

Mills adds that the consultation process suggested in the legislation would likely end up quite limited, and there appears to be no right to challenge a work notice once issued. ‘That to me feels quite undemocratic,’ he says, although ‘if there was a right to challenge you’d end up with a different sideshow of industrial disputes that nobody wants’.

As for employers’ views on the proposals, Sarah Wimsett, an associate and employment law specialist at Bevan Brittan, believes ‘it is fair to say that many public sector managers and leadership teams feel torn between their need to prioritise the delivery of public services and supporting their staff who feel undervalued or unable to makes ends meet. To the extent that they do reflect on the bill, I think they feel conflicted about it.’

Wimsett says section 240 of the Trade Unions and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992 includes limited provisions that make it an offence for individuals to wilfully or maliciously break a contract of services or hiring, if that could endanger human life or expose property to destruction or serious injury. Where this applies, any derogations need to be agreed at a local level and employers must negotiate with the unions. ‘This can lead to differences in approach and it requires a willingness on all parties to be proactive and cooperative’, Wimsett adds.

These limited provisions do mean there’s scope for minimum service levels to be looked at, but Wimsett adds that ‘the big question will be whether the Bill strays beyond what is necessary, taking into account the requirements of Article 11 of the European Convention on Human Rights’ – the right to freedom of peaceful assembly and to freedom of association. She reiterates that presently, as the minimum service levels are yet to be clarified, it’s unknown as to how restrictive these rules would be on those wishing to take part in industrial action.

The legislation is currently in the UK Parliament’s second chamber, the House of Lords, with its second reading – or debate – scheduled for 21 February. Todd is hopeful that the lawyers in the Lords will help push through some amendments that’ll water down the Secretary of State’s powers, although the consensus is that the legislation will likely pass, ultimately.

In that event, yet more disruption is likely. ‘The canny union’s going to think “how can I game the system lawfully?” There’s always been the argument that a good old-fashioned strike for a limited period serves both parties more than other avenues’, Mills says. However, ‘the proof will be in the pudding. If in a year’s time this is being used sparingly and quite sensibly then it will be much less of an issue.’

Todd believes unions are in a strong position, regardless of the Bill, due to public support and widespread indignation about the cost of living crisis. ‘It’s a big moment for unions’, he says. ‘This is an opportunity for them to stand up for these members. It shows the importance of having a collective voice in the workplace, they’re certainly being heard.’

Image credit: Matthew/AdobeStock.com