David Miliband, International Rescue Committee CEO

The 2019 Stockholm Human Rights Award winners were David Miliband and the International Rescue Committee, the organisation he leads. In conversation with IBA Executive Director, Mark Ellis, Miliband spoke about migration, the climate crisis and the need for passion, as well as reason, in confronting populism.

Mark Ellis: You’re of Jewish background, and your mother survived in Poland, hiding in a convent with her mother and sister. Then, having had help from a family, she eventually came to the UK. You said in your book: ‘for me, my family’s experience has turned refugees from a faceless category into blood and spirit. It demonstrates how our lives depend on the decisions of strangers.’ This must be with you every single day on this job?

David Miliband: Yes, because our work inevitably is about crossing boundaries. The work of our teams around the world is about reaching out across boundaries of race, religion and region. It is important to say that for the survivor generation, for my parents’ generation, the thing they sought above all to give to their children was not to have to think about what they had been through every day. The essence of my parents’ effort – I was born in 1965, so 20 years after the end of the Holocaust, the end of the War – was to make sure that we weren’t burdened with a daily sense of foreboding, dread, terror and the rest of it.

I don’t want to over-claim or wrongly claim, because I think that I was given a very secure childhood. It was only when I wrote my book that I ended up with the first line that says ‘the first refugees I ever met were my parents’. But when I was a kid, I didn’t think of my parents as refugees, I thought of them as my mum and dad. That is the greatest tribute that I can give to them, in a way, that they brought up their children without that overweening sense of how lucky we were. My dad passed away in 1994, and my mum’s not very well now, and so I have a stronger sense of how lucky I was that the UK admitted two refugees – my dad in 1940 and my mum in 1946. I won’t go into it all, but my dad’s family in Belgium were hidden in a village south of Brussels, and my mum, as you say, was hidden first of all in a convent and then by an extraordinarily brave family in Warsaw. And that is the ultimate exercise of the duty to strangers and the courage that was called on by the villagers south of Brussels, or the courage of the family that sheltered my mum. Their courage dwarves anything that we’re asked to do, at least that I’m asked to do, today.

ME: But isn’t it for that exact reason that we need to remember those stories; why we need to understand the history, particularly today?

DM: Yes, I think that’s a good point. There was a survivor generation then. I call my generation the ‘transitional generation’. We’re the generation that knew people who lived through the Holocaust, who spent the rest of their lives with numbers on their arms, but we also outlive them. We have a special responsibility both to honour the memory but also to learn the lessons. There are unfortunately far too many examples of trauma, attempted genocide, unspeakable cruelty but from which there are further acts of courage and further lessons today.

ME: You’ve talked about the staggering scale of it: 29 million refugees, 70.8 million forcibly displaced just last year alone, over 13 million people displaced, added to the previous years. One person is forcibly displaced every two seconds. It’s extraordinary. You have come up with some suggestions and some might call them controversial. You mentioned earlier about moving away from grants, and you actually advocate for refugees receiving cash and gaining access to work. Tell us a little bit about why you are advocating those two points?

DM: I always hesitate to go on about the scale of the problem, because it actually contributes to a sense of pessimism that you can’t do anything about it. I think that the biggest challenge we face is a sense of hopelessness about this. The Pope, who has been the most extraordinary champion for the world’s displaced, went to Lampedusa, Italy, in 2014, and said that the people dying in the Mediterranean were ‘evidence of the globalisation of indifference’. I know you’re not really meant to argue with the Pope, but I actually think that’s not quite right. People are not indifferent, but they feel they can’t make a difference, which is a slightly different point. Going on about the scale contributes to the sense of ‘oh my god, this is such a big problem, we can’t overcome it’. For NGOs, we have to beware going on and on about the suffering... we have to get into the solutions business.

You’ve highlighted two things. The history of humanitarian aid is that you give people tents, you give people healthcare, you give them food, and you hope they survive long enough so that they can eventually go home. The International Rescue Committee’s (IRC) point is that doesn’t work when people are displaced for 10, 15, 20 years. Just helping them to survive isn’t enough, because the truth is they are unlikely to go home.

Since 60 per cent of the world’s refugees are in cities, in the market economy, the best thing you can do is not give them a tent, or food, it’s to give them some cash so that they can rent somewhere to stay, they can pay any additional costs for their kids to go to school, they can actually be part of the economy. And that is allied to the point that since they’re in cities in the main, you need to make it possible for them to work. In most countries where refugees are hosted, they’re not allowed to work.

Since 60 per cent of the world’s refugees are in cities, in the market economy, the best thing you can do is not give them a tent, or food, it’s to give them some cash

ME: Do you think those are the crucial elements to assist in this ultimate goal of assimilation, at least for refugees in particular countries? Assimilation being very crucial, and crucial for the host country.

DM: I prefer to talk about integration rather than assimilation. I know integration is a controversial word in Sweden and there’s mixed practice about it. There was a very famous Home Secretary, the equivalent of a Justice Minister at the time, Roy Jenkins, who in the 1960s talked about assimilation sounding like the production of carbon copies of the pre-existing citizenry, but integration being about contributing to a renewal of citizenship, so that’s why I talk about integration rather than assimilation. I think that a lot of French experience shows you the dangers of trying to make carbon copies. Integration isn’t always done well, but it’s preferable to the attempt at ‘assimilation’ because it contains the notion of contribution and the evolution of a citizenship.

If you do those three things, if refugees were given the right to work, if they had cash support and if their kids were in school, and the hosting states were given macro - economic support, you’d go a long way not to ‘solving the problem’ but to addressing the symptoms of the problem, which is ultimately a diplomatic problem. The crisis of diplomacy is that civil wars are burning for 10, 20, 30 years, so refugees don’t go home.

There is one other thing, though, which is important and the Swedish experience is relevant to this: for the most vulnerable refugees, it’s not safe for them to stay in a neighbouring state. That’s what the resettlement system was designed for. Sweden takes about 5,000 resettled refugees every year. Ironically, the US President who admitted more refugees than any other was Ronald Reagan. Two hundred thousand refugees were allowed into the US on a resettlement route in 1981. Today, the Trump administration has reduced that number from 90,000 to 18,000. It’s an extraordinarily severe cut-back. That refugee resettlement route is a fourth component of a comprehensive global approach for the most vulnerable.

ME: Getting back to the cause and effect. The World Bank reports that by 2050 the effects of climate change alone will force approximately 143 million people to migrate, dwarfing any other cause. There’s a legal gap for those that are moving because of the climate crisis, and that will continue to increase. What should the international community, what should the IRC, be advocating for in this new crisis of climate change migration?

DM: That’s a great point. Here’s my take on this. First of all, just remember how important words are. The 143 million figure that you’ve quoted is not refugees. Most of those 143 million will be internally displaced. Bangladesh is very exposed to climate change in the south. Those Bangladeshis will move inland in Bangladesh. They’re not going to cross a border, in all likelihood. That’s really important for this.

ME: In 2016, 24 million people were internally displaced because of the climate crisis.

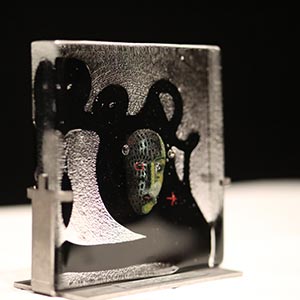

David Miliband and the IRC were awarded the 2019 Stockholm Human Rights Award © IBA 2019

DM: Yes, we’re talking about climate IDPs [internally displaced people], not necessarily climate refugees. Secondly, a refugee is someone who has a well-founded fear of persecution on social, political, ethnic grounds. The test is: is it safe for them to go home to their home country? For someone who is driven from their land by climate change, it is not obvious to me that they meet the definition of not being safe to be in their home country. That raises the standard that we apply for the designation of a refugee.

Personally, I think there is a difference between someone who is threatened by a death squad and is forced out of their own country and someone who is forced to move from one part of their home country to another part of their home country. Anyone seeking to renegotiate the 1951 Refugee Convention today is asking for trouble – both in getting any consensus and in terms of the danger of the diminution of the rights of those who are forcibly displaced.

In answer to your question of what needs to be done is an obvious point: the mitigation of and adaption to climate change. This decade is a key decade for that. We’ve wasted the last decade, in many ways. The global public good of mitigating and adapting to climate change requires an international response wholly out of kilter with the mood of the times, and that’s the generational challenge that we have to face today.

ME: The reality of the nationalist - populist movement is that the very values that were essential post-World War II, of tolerance, of open-mindedness, are disappearing at a rapid rate. It seems that the nationalist - populist movement has anti - immigration front and centre. That seems to be successful in them pushing their agenda. How do you counter that?

The danger is that we counter the passion of populists with so-called “reason”. We should have reason, but we should have passion as well

DM: There is a grave temptation to say that the world is being swept by nationalistic, xenophobic politics. It is certainly the case, but there are movements that are nationalistic and xenophobic. There is a big difference between nationalism and patriotism. I never condemn patriotism because patriotism is about pride in your own country, but not at the expense of another country. Nationalism says that if you’re going to be proud of your own country, you have to ‘do down’ on other countries, a zero-sum game. There is a growth of that politics, not just in the Western world but actually in other countries as well... but there’s also, for each and every person who fears refugees in Dallas, Texas, someone who says ‘hang on, my family were refugees’ or ‘my workmates were refugees’ and that’s why I describe this time, not as one of the disappearance of those values, but one of a polarisation of debate about those values.

Through action and words, we have to engage in that debate because it’s not true that they are disappearing, but it is true that they will disappear unless we fight for them. The danger is that we counter the passion of so-called populists with ‘reason’. We should have reason, but we should have passion as well. The politics that wants to defend the liberal international order... if we’re going to defend that we have to do it through passion and reason. Because what the populists want to say is ‘you’re just a bunch of technocrats and you’ve failed’. No – ‘you’re the politics of anger; we’re about the politics of answers, but we’re passionate about the values that underpin them’.

ME: So, are you optimistic that were we to have this discussion in five years, the pendulum would have shifted?

DM: I think it’s a longer fight than that, to be honest. Over the last 13 years, since 2006, 113 countries have seen reductions in political freedom. That means a less independent judiciary, more corrupt political systems, less freedom of the press. Those three factors are all standing behind a liberal democratic system. This is already a 13-year movement. If you want a symptom of the fact that liberal democracy is in retreat, just look at what the autocrats are saying. They are not inevitably going to win, but it is not a five-year struggle. We’ve already had 13 years going backwards, so it’s at least 13 years to push back.

The people that we’re helping are not giving up, so what right do we have to give up? If you’re a woman who’s been abused in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and you’re not giving up, how on earth have we got any excuse for giving up? If you’re a Syrian refugee who’s been bombed out of your own country and you’re living in fear in Jordan, and you’re not giving up, we have no right to give up.

I have a naive faith that this so-called ‘populist wave’ is actually producing a reaction. The truth is, there’s no answer in building higher walls or deeper moats. The people smugglers will just become more ingenious about how to get round them, under them or over them.

We have never had a more educated or connected global citizenry. People around the world have never been more conscious of the rights that others have. That fuels some of the migration, but equally it’s what fuels movements for political, social and economic change.

Mitigating and adapting to climate change requires an international response wholly out of kilter with the mood of the times, and that’s the generational challenge we have to face today

ME: So you don’t think there’s going to be a new normal? If Donald Trump were to be elected again, and the pendulum did not swing at all, then wouldn’t one be quite concerned that, despite this very nationalistic agenda, the educated class that you refer to simply is not sufficient? That we have a ratchet effect that we’re not able to reverse?

DM: If Trump is re-elected, it should certainly shatter any illusion that we as Europeans can depend on the Americans to sort things out for us. America has, throughout its history, had an erratic attitude to its role of global leadership. We’re 100 years on from the collapse of the League of Nations. Where did the League of Nations first collapse? It collapsed in the US Senate.

What we’re living through today is a retreat from post-World War II norms of American leadership, but we’re not seeing something that’s been unknown in American history. Here’s the thing though: where are people demonstrating for their rights? In Catalonia, Lebanon, Santiago, Hong Kong, last summer in Moscow, they were demonstrating for their rights, and that’s a really dangerous thing to do. It’s true that the political order is very mixed around the world. You’re right to say there’s not going to be a single order – anyone who tells you that China is going to go in a liberal democratic direction is not telling the truth. It’ll be much messier, in a way. I don’t think you have to believe that because China is succeeding as an autocratic market system, that the rest of us are doomed to go in that direction as well.