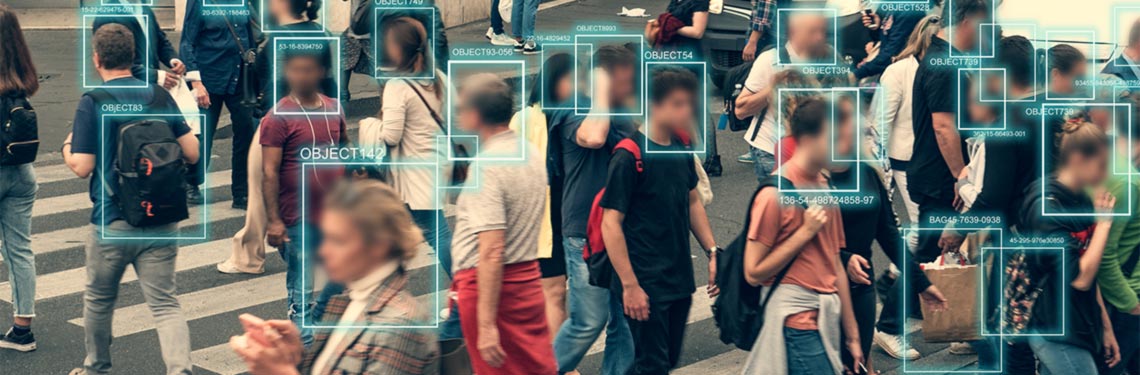

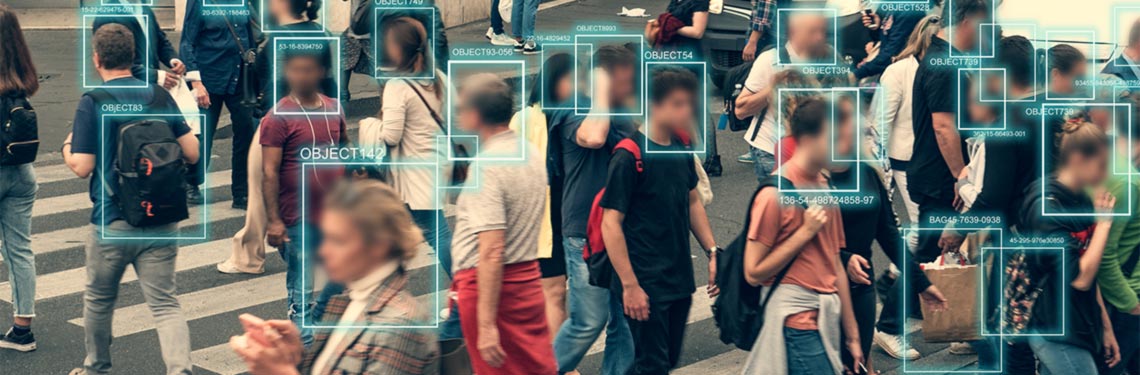

The changing faces of biometric privacy

Arthur Piper, IBA Technology CorrespondentWednesday 22 September 2021

Surveillance technology has many legitimate and important commercial uses. However, the privacy issues create a minefield that must be navigated with great care.

Over the summer, the Information Commissioners Office (ICO) released new guidance on the use of live facial recognition technology (LFR). While the position on the deployment of such devices by law enforcement agencies has had plenty of attention, this is the first piece of specific guidance on the capture and use of individuals' biometric information by private companies.

It is necessary because businesses are covered by a separate – albeit overlapping – legal framework. The full details can be found in the ICO's document, but the main rules centre around the 2018 Data Protection Act (DPA) and the UK General Data Protection Regulation.

Readers of this column may recall that civil rights activist Ed Bridges brought a case against the South Wales Police in 2019, contesting that such technologies breached his right to privacy under Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights. While the High Court disagreed with Bridges, the Court of Appeal overturned that decision.

While the Court of Appeal also allowed Bridges' case to succeed in relation to the DPA, the ruling was relatively narrow. It said that the South Wales Police had failed to consider Article 8 in the data protection impact assessment required by the DPA, but also stated that the legal framework as it stands is inadequate.

Machine learning systems are, in a very real way, constructing race and gender […] and this has long-lasting ramifications for the people who are classified

Kate Crawford

Senior Principal Researcher, Microsoft

The Home Office and the College of Policing are currently assessing how the legal framework can better reflect the Court of Appeal’s ruling.

Two issues stand out. First, the police wanted CCTV images and LFR images to be considered as equivalent. However, they cannot be comparably used. Since the LTR image is captured and stored on a digital database, the ICO considers it to be biometric data and, therefore, both more personal and more permanent than the fleeting images captured by CCTV. Such images are like fingerprints in how they can accurately identify individuals, but unlike fingerprints they can be collected covertly, on a mass scale and without prior consent or even knowledge.

Second, because the law is currently incomplete, individual police forces effectively have too much discretion in deciding how, when, why and where to implement such systems. As the artificial intelligence (AI) pressure group the Ada Lovelace Institute pointed out, this is hardly ‘an appropriate legal basis for interfering with individuals’ data and privacy rights’.

Great expectations unmet

The ICO's most recent intervention could be expected to build on these findings. But, it appears strangely hesitant.

First, it focuses on the use of LFR for identification and categorisation only. That excludes ‘verification’ – presumably the type used on smartphones for users to log in – and other one-to-one uses. Nor does the opinion cover online facial recognition technology (FRT). The camera systems need to be deployed outside the home, for example in private offices or public spaces, such as shopping centres.

What the commissioner wants to concentrate on in this opinion is systems that ‘capture the biometric data of all individuals passing within the range of the camera indiscriminately’. Lawyers wanting clarification on the uses of facial recognition systems by private companies outside this range will have to wait.

Second, while the guidance reiterates the basic premise of the DPA around collecting data without justification or consent, transparency and regard for potential bias, it draws a line at forbidding any type of possible deployment. Instead, it warns data controllers that they need to do the right due diligence and put in place proper safeguards and governance processes.

It is not that surprising that the ICO's findings are based on 14 uses of the technology by actual companies. And equally unsurprising is that most of those breached aspects of the DPA. In that respect, the guidance is a timely reminder of what businesses need to do if they continue to develop or buy such systems.

The main message here is that organisations, technology providers and vendors need to do proper and specific data privacy due diligence, according to the IBA LPRU’s Senior Legal Advisor Anurag Bana. ‘While the rules for LFR for online use are yet to be released, there has been a big focus on duty of care, which is echoed in this opinion through its emphasis on understanding the potential impact of these technologies on people's lives’, he says.

In China, where online gaming for minors has been restricted, industry players, such as gaming-giant Tencent, are reportedly using facial recognition technologies to enforce the new law. Given that the UK's Online Harms Bill 2021 is also designed to protect children's wellbeing and mental health, it is not impossible to imagine that some form of facial recognition technology could have a role to play.

Deep-rooted potential harms

In the opinion, Commissioner Elizabeth Denham says that she would find it hard to conceive LFR passing the requirements for DPA in environments such as shopping centres. Citing a recent case in Canada, she says it is obvious that individuals ‘are unable to reasonably withhold consent as the cameras operate discretely’.

Activists, though, point to deep-rooted potential harms LFR can do through the way it automatically classifies people. If a billboard, for instance, used facial recognition cameras to capture the images of passing faces, the software behind it automatically categorises individuals by how they look. This can be along the lines of age, gender, ethnicity or even clothing styles and brands.

As Kate Crawford, a Senior Principal Researcher at Microsoft, points out in her 2021 book Atlas of AI, such categorisations carry with them inherent biases that feed directly into the software from training data.

The non-commercial UTKFace dataset, for example, contains over 20,000 photographs of people of all races and ages. It is frequently used for research purposes, including FRT – although not by commercial businesses. This and other such databases have been widely criticised in academic circles, as gender is defined simply as male or female, and race is categorised into one of five classes: White, Black, Asian, Indian and Others. Many proprietary databases, which form the bedrock of LFR, use similar taxonomies.

Crawford sees such simplistic classifications as irreparably harmful because they create false assumptions that people of certain races or genders have well-defined, objectively knowable characteristics. ‘Machine learning systems are, in a very real way, constructing race and gender: they are defining the world within the terms they have set, and this has long-lasting ramifications for the people who are classified’, she says. Repressive regimes around the world have essentialised people in such ways throughout history – and this logic is baked into LFR, she says.

While the ICO's opinion will not be the last word on LFR, it is likely to be so from Denham. She will step down shortly and is likely to be replaced by John Edwards, currently New Zealand’s Privacy Commissioner. Edwards has been charged with reducing ‘unnecessary barriers and burdens’ on international data transfers following the UK's departure from the European Union. It will be interesting to see how his appointment will impact the UK's increasingly complex regulatory web governance in the shifting digital world.

Arthur Piper is a freelance journalist. He can be contacted at arthur@sdw.co.uk

Header pic: Shutterstock.com/DedMityay