Blockchain lessons from overseas

Back to Real Estate Committee publications

Graham Collier

Mills Reeve, Manchester

graham.collier@mills-reeve.com

The Dreamvar case[1] still occupies the minds of those involved in the property legal sector, not least conveyancers. Meanwhile, creeping into the consciousness of the same lawyers is the concept that blockchain could play a role in the future of the property world. Could embracing technological advances provide us with the answers being sought? Do we have enough knowledge to establish what the question actually is?

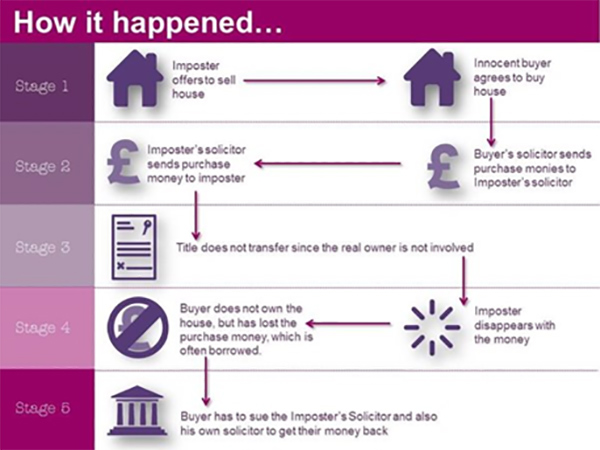

By way of background, the Dreamvar litigation arose out of the fraudulent sale of a residential property, with the fraudulent seller having stolen the real proprietor’s identity.

The case revolved around who should ultimately (despite their innocent involvement) be liable to a buyer who finds themselves without either their money or the property they thought they were buying – the seller’s solicitor, the buyer’s solicitor or the estate agents – in circumstances where the purported seller isn’t who they say they are. My colleagues Niall Innes and Jacqui King from the Mills & Reeve insurance team emerged victorious acting for one of the parties, Winkworth, against whom the claim and appeal failed. With the decision in Dreamvar meaning that the risk of conveyancing fraud seemingly now falls on the buyer’s solicitor (notwithstanding the fact that the seller’s representative bears responsibility for ensuring that the seller is in fact the seller!), Dreamvar has understandably sent shockwaves through the legal market, with those involved seeking to protect themselves against the associated risks.

It has been suggested by some that blockchain could be the solution, providing comfort in the areas of security and trust that have fallen into doubt recently. Coupled with this, there is a view that adopting blockchain could help to streamline the process of property transactions. Blockchain (for the uninitiated) is probably most famously known as the technology behind the cryptocurrency bitcoin.

Creation of a private blockchain (to which designated parties will have access to certain data) could be the next step in a digitisation process already under way at Her Majesty’s Land Registry (HMLR) – with blockchain providing an infallible record of ownership and all agreed terms of a transaction. This does not mean that an interest in property would be a tradeable asset in the manner of bitcoin, but instead that blockchain would ensure necessary processes are followed and information verified centrally. The British government has already sought to embrace this by introducing the Government Gateway system to provide access to government internet-based services. This shows a real desire to centralise verification of identity and on the back of Dreamvar that’s no bad thing.

Indeed, steps are being taken to establish how the use of blockchain could form part of the registration process. We have seen the first properties transferred using blockchain.[2] Use of blockchain was trialled by the Swedish Land Registry in 2017, with the creation of smart contracts (signed digitally and automatically verified), and HMLR explored the use of blockchain in 2019 as part of its Digital Street programme, running a recently completed transaction through its own prototype system to ascertain what the impact of it would have been on the transaction.

In terms of streamlining, the ‘parties’ with access to the blockchain could, for example, extend to banks and Her Majesty’s Revenue & Customs – and the information contained within it could be sourced directly from search providers. The flow of centralised and verified information between parties will enable an increased efficiency in the due diligence post-completion process.

While work is being done to see how blockchain can be used across the property ‘piste’, it doesn’t feel like we are quite there yet on the implementation side of things. While HMLR is carrying out its trials, it remains resistant to accepting electronically signed documents (while the Law Society position is more relaxed). Similarly, the benefit of the ‘streamlining’ will be very much dependent on which parties buy in to the concept – for example, will search providers forego their fees? And how will their information be updated? The local land charges migration to HMLR showed how slow and disjointed a migration process could be. Blockchain will need to be widely adopted to have the benefits some envisage on the streamlining side of things.

It is worth noting that questions also remain around whether adoption of a fully digitised system will provide the comfort and security being cried out for. By way of example, Australia’s electronic exchange and transfer platform PEXA (Property Exchange Australia) has featured in the news for the wrong reasons, with access obtained to firms’ property transfer accounts and money syphoned off to unrelated accounts (despite more than two million transactions having been completed under it). This shows that an increase in the digitisation of transactions may not result in them being entirely free of issues.

In reality, any blockchain used would only be as secure as its coding, with the structured nature of the record keeping meaning that any inaccuracies captured or added to the system will remain there until rectified. Some have also suggested that private blockchains amount only to a form of database, not new technology, with others taking the view that the real value of blockchain be found in countries with less developed land ownership record systems than HMLR’s existing database.

At this moment in time, it is difficult to see that the role of a lawyer would become redundant, or in reality, change that much. We are several steps from a scenario in which land becomes a commoditised item, transferable by clicking through a series of tasks. In all but the most straightforward transactions, due diligence will be required to enable an appraisal of risk for a particular client and negotiation of the terms of any transaction. Any agreement to apportion that risk will require the human touch.

There is a real desire to add security and certainty to the property system on the back of Dreamvar – from the parties involved, the wider property world and the legal representatives seeking to avoid fraudulent scenarios. Whether the use of blockchain will result in that still needs to be properly established in the property world and those affected by Dreamvar will need to ensure that they are sufficiently protected in the interim.

[1] Dreamvar (UK) Ltd v Mischon de Reya andP&P Property Ltd v Owen White and Catlin LLP [2018] EWCA Civ 1082.