Agenda for the next President of the United States

Michael Goldhaber, IBA US CorrespondentWednesday 12 August 2020

As President Trump’s four years in office comes to a catastrophic end, Global Insight assesses what needs to change for the sake of America and the world.

In a friendly sit-down interview this summer, Fox News prodded the President to name his ‘top priority items for a second term.’ The President’s reply was worthy of a beauty contest parody: ‘One of the things that will be really great – the word experience is still good, I always say talent is more important than experience, I’ve always said that – but the word experience is a very important word. It’s a very important meaning.’ He eventually rambled into attacks on his political enemies, without ever hinting at a single priority.

One obvious policy agenda would be for the next President to reverse this administration’s systematic attacks on the environment, immigration and internationalist diplomacy. But, an ambitious forward-looking agenda is imaginable too. Democrat candidate Joe Biden has invoked Franklin D Roosevelt, proclaiming that the ‘moment has come for our nation to deal with systemic racism – to deal with the growing economic inequity that exists in our nation.’

Economists who focus on inequality see a real opportunity in this unique moment. ‘Today’s confluence of nightmares has made the country open to bolder change,’ says Dr Irwin Garfinkel, Director of the Columbia University Center on Poverty and Social Poverty. ‘There may be an opportunity next year to fundamentally start solving the persistent problems of the past 40 years,’ says Michael Linden, Executive Director of the Groundwork Collaborative and a fellow at the Roosevelt Institute. ‘The priorities will have to be police accountability, combined with an economic package laying big foundations for sustainable growth.’

Repairing the destruction

President Trump has passed just one piece of major legislation, the 2017 tax cut, which Joe Biden has pledged to undo should he be the next US President. As for executive and regulatory action, the Trump regime has been hyperactive. As Global Insight has documented, it has focused obsessively on immigration, the environment and foreign policy. (See ‘Trouble at the border’, Global Insight, June/July 2019; ‘The USA’s assault on environmental protection’, Global Insight, Feb/March 2020; ‘Present at the destruction’, Global Insight, Dec/Jan 2019). The Migration Policy Institute counted over 200 immigration tweaks in the first half of President Trump’s term, and the pace has since accelerated. The New York Times tallies 100 environmental rollbacks. President Trump has never met an existing treaty he likes (See ‘Trump’s treaty undoing project’, Global Insight, Feb/March 2017; ‘America’s withdrawal from human rights’, Global Insight, Aug/Sept 2018).

There may be an opportunity next year to fundamentally start solving the persistent problems of the past 40 years

Michael Linden

Executive Director, Groundwork Collaborative and a fellow at the Roosevelt Institute

In an ideal world, says Sarah Pierce, a policy analyst at the Migration Policy Institute, the next President would reverse Trump-era changes legislatively ‘to prevent policy from turning into a swinging pendulum.’ More realistically, she continues, ‘We’re in the midst of a public health pandemic, economic crisis and coming to terms with deep racial inequities. Anything else is at best a fourth priority.’ The good news is that ‘Trump did everything without Congress, so everything can be undone without Congress.’

To be sure, revisiting rules will provoke legal challenges that are the mirror image of today’s. But judges have a soft spot for agencies that try to fulfill their mission, rather than undermine it. In a good faith review of Trump era rules, both ‘the science and the law will clearly point in the direction of different results,’ says Avi Garbow, who was the chief lawyer at the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) under Obama. ‘Directing agencies to actually follow their statutory mandate – for instance, to protect health and the environment – is not political pandering.’ Executive orders, while faster than rule changes, will be vulnerable to court challenges in some cases.

US President Donald Trump talks with US Border Patrol Chief Rodney Scott while touring a section of recently constructed US–Mexico border wall in San Luis, Arizona, US, 23 June 2020. REUTERS/Carlos Barria

The regulatory state will transform itself on day one by simply resuming enforcement, which had abated before the pandemic, and has since been shamelessly suspended. On the environmental front, the most impactful changes have been those that spike carbon emissions – hastening global warming and causing thousands of premature deaths a year attributed to particulate matter. Among the highest profile of the EPA’s anti-climate measures are the Affordable Clean Energy Plan; the Safer Affordable Fuel-Efficient Vehicles Rule; the hypocritical effort to pre-empt California’s tough rival plan for auto pollution; the ‘Science Transparency Rule’ (disregarding state-of-the-art studies that justify carbon regulation); and several rules that spike emissions of methane. But the war on climate is a whole-of-government effort. The US Department of Energy has lowered efficiency standards for industrial equipment, home appliances and light bulbs. The US Department of the Interior has opened the public domain to fossil fuel exploration, hindered the development of offshore wind by requiring supplemental reviews, and promoted fossil fuel development by excluding climate from Environmental Impact Statements. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission has used an obscure price rule to protect the coal sector from renewable rivals.

On immigration, the Trump administration’s obsession within an obsession is asylum. Frustrated when courts wouldn’t let it cage children, the White House has churned through ways to deter asylum seekers. A significant change would be to halt the pandemic practice of simply expelling applicants at the border; to stop the preexisting practice of manufacturing long waits at the border, stop making applicants remain in Mexico to await hearings; rescind the rule requiring Central Americans to first seek asylum in Mexico; reverse the rule against applicants working; and roll back the regulation that heightens evidentiary burdens, narrows legal standards and creates routine grounds to deny asylum.

Beyond asylum, top priorities ought to include lifting the ‘immigrant ban’ (suspending green cards and work visas during the pandemic); restoring legal immigrants’ access to social services; and cancelling the wealth test (also known as the public charge rule). In addition, the President’s challenger has proposed to lift refugee admissions from the paltry levels of 18,000 in 2019 and 6,000 in 2020, to a more respectable 125,000.

That leaves the three flash points richest in symbolism. The wall: not building it; protecting ‘Dreamers’ (and giving them Obamacare); and lifting the travel ban that galvanised the resistance. These moves might necessitate the recruitment of a patient Solicitor General and a thick-skinned social media director!

Present at the reconstruction?

Destroying the world order appears to be among President Trump’s preoccupations, and destruction invites reconstruction. At the top of the agenda for 2021 should be signalling to America’s democratic allies that it’s back, and that alliances and partnerships matter. The unfortunate reality is that America’s ‘capacity for exercising a global leadership role has collapsed,’ according to Ivo Daalder, the ex-US Ambassador to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). To reassert it, says the former State Department Legal Adviser John Bellinger, the US will first need to restore a strong State Department (and functional National Security Council).

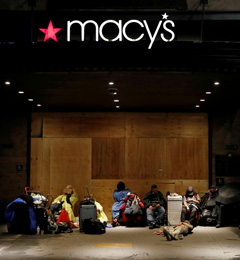

Homeless people sleep under the awning of the boarded-up Macy’s Herald Square store, as protesters rally against the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis police custody, in New York City, New York, US, 3 June 2020. REUTERS/Andrew Kelly

Yet the work of rebuilding US diplomatic institutions ‘will take a generation,’ cautions Council on Foreign Relations president Richard Haass. Recovering their reputation may be impossible. America is ‘a country whose convening power has substantially eroded,’ laments former US Trade Representative Charlene Barshefsky. ‘We can’t just go out and expect our allies will love us again,’ concurs Daalder. ‘The rest of the world looks at us and says the fact that you could elect someone like Donald Trump and 40 per cent of you still like him means you’re a different country and we can’t rely on you.’

The US is set to exit the Paris Agreement the day after Election Day, in November. After that, Haass and Bellinger think the most urgent treaty to engage with is New START (Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty), which expires in February 2021. ‘The last thing we need is new round of nuclear competition with Russia,’ says Haass. Next, there’s a consensus that the US must swiftly reverse its withdrawal from World Health Organization (set to take effect in July 2021). A final move that might be reversed easily is the shrinking of the US military presence in Germany. Reinforcing our commitment there ‘would send a powerful signal to both Europe and Russia,’ argues Haass.

Then comes a long parade of more fraught issues. While the next President is likely to reengage with Iran, even its fans see little point in simply resurrecting a nuclear deal whose restrictions begin to expire in October. And though most Democrats and Never-Trumpers yearn for US leadership on human rights, some remain conflicted about rejoining the United Nations Human Rights Council, or aiding the International Criminal Court’s Afghan prosecution. Other moves, like the US embassy’s relocation from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, may prove to be faits accomplis.

America’s capacity for exercising a global leadership role has collapsed

Ivo Daalder

Former US Ambassador to NATO

To the extent the US can reconstitute a larger world order is debatable. ‘There’s no question of restoring the old order because US supremacy is gone,’ says Daalder. ‘Global institutions are near, if not in, collapse.’ His preferred platform for a new world order would be a Group of Eleven (G11), including the Group of Seven (G7) plus Australia, the European Union, NATO and South Korea. Barshefsky generally likes the idea of building cooperative structures with likeminded democracies. She dreams of the US leading the nations of Europe and an expanded Trans- Pacific Partnership into a multilateral agreement on tougher world trade rules, which in the long run the World Trade Organization would accept. Haass isn’t hung up on any institutional architecture. ‘It’s really a matter of who’s relevant, willing and able to be in the room on each issue,’ he says. A forum for public health, for example, might bring the Gates Foundation and Big Pharma to the table.

But, even the most confirmed internationalists know that pride of place must be given to domestic policy. For the challenges of 2021 will resemble those of 1918 more than 1919, and 1933 more than 1945. ‘Job one will be to get Covid-19 under control,’ according to Tony Blinken, who is a senior foreign policy adviser to the Biden campaign, and a potential National Security Adviser.

We need an inclusive economic bill of rights that is antiracist instead of racist. What better time to enact one than when we are reeling from a pandemic that’s eating into the fabric of our public health and economy?

Darrick Hamilton

Director, Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity

Ambassador Barshefsky believes that America must prioritise domestic policy more broadly for strategic reasons. ‘For the US, job number one, two, three, four and five is to get its own act together,’ she says. ‘Plans for infrastructure buildout, labour, environment, technology and innovation, education – these kinds of elements are the single most important thing that must be done, because if we are not economically successful at home, we will not counter China. All of these different elements of domestic policy, including immigration, these are the number one jobs. First you strengthen yourself, because China is the single greatest challenge that the US faces.’

Serious economic reform

The key to strength is unity, and in order to achieve that, what’s required, perhaps more than ever at this moment, is racial awareness. ‘Anyone who doesn’t see the linkages between our political economy and race hasn’t been paying attention,’ says Darrick Hamilton, Director of the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity. ‘When we see the killing of George Floyd by state action, when we see the disproportionate impact of Covid-19 on African Americans and Latinx peoples, it indicates the devaluation of the most vulnerable groups in our society.’

The most direct response to the protests would be to enact the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act. Introduced by Senator Kamala Harris and Representative Karen Bass, this House-passed bill would ban chokeholds, create a national registry of abusive police officers and end qualified legal immunity for police officers.

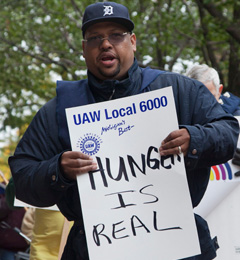

Members of United Auto Workers Local 6000 picket the state of Michigan office building to protest the state’s plan to drop more than 12,000 families from the welfare rolls. Detroit, Michigan, US, June, 2020. Alamy Stock Photo/Jim West

Racial justice needs to be part of a broad economic response to Covid-19, covering poverty, education, healthcare and the environment ‘We need an inclusive economic Bill of Rights that is antiracist instead of racist,’ says Hamilton. ‘What better time to enact one than when we are collectively reeling from a pandemic that is eating into the fabric of our public health and economy?’

In a series of addresses this summer, Biden put forward an immense jobs and investment programme. Trumpeting the formation of a caregiving workforce and a post-Covid-19 industrial policy, he proposed over $150bn a year for ten years to subsidise childcare, eldercare and universal preschool; high-tech research and development; and federal purchases of products ‘made in America.’ But the big ticket item is a green stimulus.

The President’s challenger wishes to invest $500bn each year on clean energy and infrastructure – upgrading a million green buildings a year, and pushing toward an emissionfree power sector by 2035. Biden’s job plan is similar to the Green New Deal, without the absolutist goals. Its strategy is to wrap climate policy in pandemic policy – using the crisis of 2020 to respond to the crisis of the century.

Beyond the creation of new jobs, a number of bold anti-poverty ideas are being contemplated. The simplest would double the minimum wage by 2024, giving 33 million Americans a raise. Among the most effective would be to give rent vouchers to all who are eligible for the existing programme. In one stroke, the number of Americans with subsidised housing might quadruple. Columbia’s Center on Poverty predicts it would reduce US child poverty by a third – at a time when evictions and homelessness are poised to soar.

A pedestrian pushes a stroller as people wait in line outside to buy supplies at the Martin B Retting, Inc gun store amid fears of the global growth of Covid-19 cases, in Culver City, California, US, 15 March 2020. REUTERS/Patrick T Fallon

But, in the fight on inequality, ‘baby bonds’ are the favourite idea of both Hamilton and Garfinkel. The wealth gap between Black and white people between 18 and 25 now stands at a shocking ratio of 16 to one. Baby bonds would nearly close this gap, according to a Columbia Center on Poverty study. One version, promoted by Hamilton and Senator Cory Booker, would offer all American newborns $1,000, and add up to $2,000 annually for low-income children. ‘It would send an incredible message to poor children of every race that you’re going to have capital,’ says Garfinkel. ‘It very much meets the moment because there’s a racial justice dimension.’

Students of US inequality policy find themselves in a state of intellectual ferment, and unfamiliar hope. At the same time, they’re painfully aware that all of these ideas are nonstarters if Republicans control the Senate, or retain the filibuster.

First you strengthen yourself, because China is the single greatest challenge that the US faces

Charlene Barshefsky

Former US Trade Representative

Another forward-looking policy priority for most Americans, of all races, is the prevention of gun violence. This summer has seen a high death toll in several cities, and it’s only a matter of time before the next Parkland. The likeliest reforms to be enacted fast are those that have already passed the House of Representatives: instituting a universal background check, requiring it to be completed before any gun sale, and closing the ‘boyfriend loophole’ for a restraining order against convicted stalkers. If the Senate gets rid of the filibuster, then Washington’s response won’t stop at hopes and prayers. Of course, that’s a big ‘if.’

Serious democratic reform

To achieve progress with these sorts of ambitious agendas will require significant democratic reform. Whoever is President in 2021, they will immediately face a set of structural democratic reforms that Congress has put at the front of the line. After Democrats captured the House of Representatives in 2018, their first move was to pass a jumbo democracy bill known as HR-1. On voting rights, HR-1 responds to the reality that US elections often fail to register the people’s will. On ethics and campaign finance, HR-1 responds to the perception that officials put self-interest and donor interest before the public.

Though HR-1 was born in response to the flaws of the 2016 election, it remains very much of the moment. ‘The reason we are seeing an outpouring of frustration on the streets is because the anti-Trump majority have felt unable to make their voices heard at the polls,’ says Daniel Weiner, Deputy Director of the Brennan Center for Justice’s Election Reform Program. At a deep level, Linden argues that the protesters’ grievances flow from the democratic crisis. After all, if not for its long history of disenfranchisement, America would not have so much structural racism in criminal justice and public health, nor such a patchy safety net. Linden concludes: ‘The last few months strengthen the case for both serious democratic reform, and serious economic reform.’

Residents affected by the economic fallout caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, line up in vehicles to collect groceries during a San Antonio Food Bank distribution in San Antonio, Texas, US, 17 July 2020. REUTERS/Adrees Latif

HR-1’s first virtue is to acknowledge Russian election meddling. It would deter foreign hackers by retiring paperless polls, regulating poll vendors and auditing electronic results. It would deter foreign trolls by forcing Facebook et al to disclose all advertisers, banning voter deception and requiring corrective information. It would deter foreign donors by forcing ‘dark money’ groups to disclose their donors – and by unfreezing the Federal Election Commission. A total redesign aims to shake the Commission from its paralysis, so it can resume enforcing the foreign donor ban, along with the rest of election law. (See ‘How US election law logged off,’ Global Insight, April/ May 2018).

Perhaps even more importantly, the House hopes to end racialised voter suppression, and expand voter access. ‘Frankly, the concerted effort to keep Black and brown people from voting accounts for much of the Trump era’s rancor,’ says Weiner. (See ‘Laboratory of autocracy,’ Global Insight, April/May 2020). If the President and Senate enact HR-1 next year, over three million ex-felons will be able to vote. Up to 50 million citizens would be registered automatically at motor vehicle, social services and college offices. Early voting and an election holiday would make it easier for them to follow through at the polls. A companion bill (to be passed again in the John Lewis Voting Rights Act), restores supervision of voting districts with a racist history. That would overrule Shelby v Holder, where the Chief Justice suggested that racism is no longer a concern in American society. Parting ways with the Supreme Court on a second key question of democracy, HR-1 would ban partisan gerrymanders. (See ‘Gerrymandering: Does the road to autocracy run through Wisconsin?’ Global Insight, Oct/Nov 2017). Instead it would form independent redistricting commissions for all 50 states – or rather, all 51. For the House recently voted to make majority-minority Washington DC the 51st state, in the suitably named HR-51.

President Trump has pursued an agenda openly pushed by big campaign donors, Weiner says, while spurning public opinion. Consider the 2017 tax cut, Obamacare repeal, and climate deregulation. (See ‘Scott Pruitt vs. the Environmental Protection Agency’ Global Insight, June/July 2018). HR-1 would weaken the sway of money in politics by generously matching public funds to small donations. True, Citizens United won’t let Congress limit ‘independent’ political spending. But by unleashing the FEC, the House hopes to police coordination between the campaigns and the ‘super political action committees’ that funnel plutocratic cash.

By any account, the Trump Presidency has revealed that federal ethics rely heavily on custom rather than law. HR-1 would require future Presidents to divest problematic assets – and to show the public their tax returns. It would address cabinet conflicts and obstruction by giving the Office of Government Ethics final say on recusals and waivers, and insulating it from presidential control.

For all its sweep, HR-1 overlooks vital structural reforms. In the latter half of his term, President Trump has pushed the bounds of his emergency powers (building the Mexican border wall) and war powers (assassinating Qasem Soleimani), while compromising bureaucratic integrity and independence by purging Inspectors General. Liz Hempowicz, Director of Public Policy at the Project for Government Oversight, urges Congress to fortify these post-Watergate restraints on the executive. Alas, she suggests weakening the Presidency will be low on any President’s agenda.

But by far the biggest barrier to popular will is beyond the House’s reach. The Senate filibuster rule allows a mere 41 Senators – representing an even smaller percentage of the US population – to block any law save one budget measure a year. ‘The filibuster is the chief obstacle to a party that controls the presidency accomplishing their goals in Congress,’ says political scientist David Faris of Roosevelt University. ‘They can’t do anything else unless they abolish the filibuster.’ They certainly couldn’t pass HR-1. ‘The list of to dos is very long,’ says Linden. ‘That’s part of the reason we need to start with filibuster reform and voting reforms. One whack at the apple is not acceptable. The moment requires more than that.’

Michael Goldhaber is the IBA’s US Correspondent. He can be contacted at michael.goldhaber@int-bar.org