Country updates – December 2020

Uruguay

Amendments to the construction defects liability scheme

Federico Carbajales, Montevideo

Law 19.726 came into force to amend the ten-year liability scheme for construction defects. It is applicable to all construction deals agreed from January last year and updates the liability scheme for construction agents that existed under the Uruguayan Civil Code and Law 1816 of 1885.

One of the amendments brought in different time limits for guarantees based on the type of defect, changing the blanket ten-year period to terms of ten, five or two years. The window of 20 years to bring an action after the occurrence of a defect was reduced to four years.

The law also reaffirmed the liability of construction agents when properties collapse, because they may only waive liability in the event of a non-attributable external cause.

Key amendment

The most significant amendment is the change to guarantee terms based on the type of defect and its seriousness. Architects, engineers, constructors and/or entrepreneurs will be held liable for:

• defects that, in whole or in part, affect the stability or solidity of the property (‘structural collapse’) or make the property unsuitable for the agreed use – expressly or impliedly – or otherwise for such use as ordinarily intended (‘functional collapse’), should these defects be verified within a ten-year term;

• any other defects, except for those only affecting the work’s completion and finishing elements should these defects be verified within a five-year term; and

• defects only affecting the work’s completion and finishing elements, should these defects be verified within a two year term.

The ten-year term was preserved for the most serious faults because in these cases the safety is at stake. The other defects with shorter terms are minor and the limit of two or five years was deemed to be reasonable for these faults to be verified.

Does the law allow any agreement with different terms?

In the case of defects under point (1), the answer is no. This provision is public policy and, therefore, the parties may not deviate at all from this law by means of any private agreement.

Doubt arises in the case of defects under points (2) and (3) since the relevant governing paragraph in the law fails to make any reference to public policy and therefore leaves a margin for interpretation.

Liability and waivers

The law reaffirms the objective nature of liability for all defects, and professionals may only waive liability in the event that there is a non-attributable external cause, such as force majeure, an act or omission of a third party or an act or omission of the principal. Conducting due diligence is therefore not enough to waive liability.

Moreover, in the case of defects under (1), architects, engineers, constructors and/or entrepreneurs will be held liable in the event of structural collapse or functional collapse even if the materials were supplied by the principal.

The term for claiming

The law reduces the term within which an action after the occurrence of a defect must be brought from 20 years to four years for all cases, including structural collapse and functional collapse.

Other amendments

The law includes some other important amendments, namely:

• it differentiates between constructors and entrepreneurs, which opens the discussion to the possibility of including real estate developers in the list of liable parties;

• it includes within the causes of defects those caused by inappropriate work management or calculation errors;

• it expressly sets out that terms within which defects may occur will be counted from the acceptance of the work; and

• it expressly repeals sections 35 and 36 of Law 1816, which expanded the effects of ten-year liability enshrined under the Civil Code for any defects noted in the work.

|

Federico Carbajales is an Associate at Guyer & Regules in Montevideo, Uruguay. He can be contacted at fcarbajales@guyer.com.uy.

|

Argentina

Renewable Energy Projects

Santiago J Barbaran, Buenos Aires

Argentina faces a difficult situation. Last year a new government took office with two major challenges: to reinvigorate the economy and negotiate the near default of debt.

Some progress has been made. Argentina recently finished negotiations with its private creditors, having secured an agreement with both international and local creditors. The government agrees with the concept of debt sustainability and this is critical to finding a solution to the solvency issue. Next year it will negotiate with the International Monetary Fund to reschedule its debts.

However, the country has been in almost six months of quarantine because of the coronavirus pandemic. The Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean has estimated that the economy will shrink by about 10.5 per cent this year,1 double the figure for 2018/19 when it shrunk by about five per cent.2

The history of the country shows that every crisis generates more poverty and that economic growth is essential not only to comply with creditors but also to create a path to the future.

Energy matrix 2015-2019

Law 26,190 of 2006 declared that the generation of electric energy from renewable energy sources was a matter of national interest. Article 2 stated that within ten years renewable energy sources should account for 8 per cent of all electricity consumed nationally. After that target was missed, the law was modified by Law 27,191 of 2015, which extended the deadline to 31 December 2017.

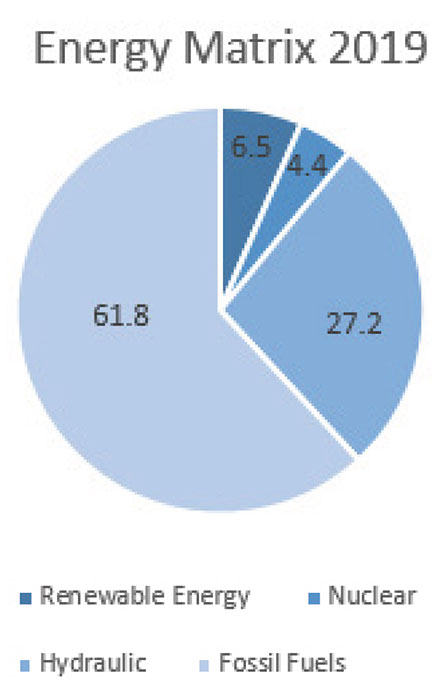

Various governments have sought to increase the use of electricity generated from renewable sources. There is a valid argument for this aim: the Argentine energy matrix is highly dependent on fossil fuels. The following chart shows the energy matrix last year:

Wholesale Electricity Market Clearing Company (CAMMESA) Report 20193

The matrix is 2017 was as follows: nuclear one per cent; hydraulic 32 per cent; renewable energy five per cent; and fossil fuels 62 per cent. Argentina started this year covering eight per cent of the electricity demand with renewable energy.4

The government implemented the RenovAR programme to increase the percentage of renewable energy in the matrix. At present wind power provides 2,197 megawatts, solar 459MW, bioenergy 171MW and hydraulic 496 MW.5

Covid-19 regulations

In March this year, Decree 260/2020 declared Covid-19 a pandemic situation in accordance with the World Health Organization. This situation had showed no sign of abating by October.

Consequently, Decree 297/2020 stated that people had to be isolated and were not allowed to circulate. Some activities were declared essential and could continue. These activities were mainly related to food production, public work and public administration.

In April, Administrative Decision 468/2020 stated that people involved in private energy works could also circulate, therefore allowing renewable projects to continue. The government showed support for this public policy.

However, the response was far from simple as there were countless situations that could not be solved because of the pandemic, such as machinery importation, provincial regulations and workers being infected with Covid-19. Thus, numerous projects were developed slower than expected.

The RenovAR programme stipulated different dates and conditions for the awardees of the projects. If the awardees did not achieve the stages of financial closure, construction start date, equipment arrival date and commercial habilitation date, they would be fined.

As a consequence of the pandemic, the government decided to extend the deadline to sign the contracts and, consequently, the commercial habilitation date (Resolution 227/2020 of the Secretary of Energy) until 30 November this year. This is very significant as companies have lost time because of the quarantine situation and the government has showed support by extending the dates.

Law 27,191 stated that by 2025 renewable energy sources must contribute 20 per cent of national electricity consumption, implying a present shortfall of 12 per cent.

At present Argentina also faces restrictions on high energy transport. In accordance with market sources, for the next and fourth round of the RenovAR programme, it was suggested that the bidders should include in their offers a proposal to extend transmission lines, previously defined by the state. With the change of government this project was suspended.

Argentina has succeeded in generating eight per cent of its energy from renewable sources. Now it faces the significant challenge of attaining 20 per cent. The main obstacle to achieving this proportion is reaching a political consensus to underpin this public policy, in the general context of economic difficulties.

Conclusion

At different times, Argentina has shown resilience to recover from major crises, in 1989 and 2001. This year, the pandemic has caused the country’s debt to increase significantly so the solution is more complex.

The public policy of diversifying the energy matrix to include renewable sources has taken almost 20 years. A process has been initiated that, hopefully, will prove beneficial to Argentina generally. The debate is not only about growth but sustainable growth.

Notes

1 Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean www.cepal.org/es/publicaciones/45782-enfrentar-efectos-cada-vez-mayores-covid-19-reactivacion-igualdad-nuevas accessed 13 September 2020.

2 National Institute of Statistics and Census www.indec.gob.ar accessed 13 September 2020.

3 CAMMESA https://portalweb.cammesa.com/Pages/PgInformeAnual, accessed 13 September 2020.

4 Ibid.

5 https://despachorenovables.cammesa.com/renovables accessed 13 September 2020.

|

Santiago Barbaran is a senior associate at Estudio Beccar Varela in Buenos Aires. He can be contacted at SBarbaran@beccarvarela.com.

|

Australia

Comprehensive reform package to target defective building work

Andrew Chew, Sydney

Christine Covington, Sydney

Louise Camenzuli, Sydney

The parliament of New South Wales recently passed two pieces of legislation to address issues that have arisen over a long period of time about deficiencies in the quality of building and construction work across the state. The introduction of the Design and Building Practitioners Act 2020(the ‘DBP Act’) and the Residential Apartment Buildings (Compliance and Enforcement Powers) Act 2020 (the ‘RAB Act’) follows the Shergold-Weir report into the building and construction industry in 20181 and the appointment of the first NSW Building Commissioner in August last year.

The DBP Act introduces a number of additional requirements on building practitioners, including that building practitioners:

• owe a statutory ‘duty of care’ to landowners and subsequent land owners;

• are properly qualified and recognised by professional bodies, adequately insured and registered with the NSW government; and

• issue compliance declarations that confirm their work complies with the Building Code of Australia (BCA).

These changes are designed to prevent defective building work by ensuring building practitioners have increased duties to landowners, provide the certifications required to allow principal certifiers to issue occupation certificates and have the necessary insurance to cover their liability if they breached their duties.

The RAB Act is designed to increase the governance framework to minimise defective residential apartments and inadequate certification process in residential apartments by:

• giving the Secretary of the Department of Customer Services the power (which will be delegated to the building commissioner) to issue stop work orders and building work rectification orders, and prohibit the issuing of occupation certificates; and

• increasing the regulatory and enforcement powers of government to investigate and prosecute building practitioners who have engaged in defective work.

Design and Building Practitioners Act

The DBP Act was introduced as a Bill to the NSW parliament late last year and, after more than 70 amendments by the government, opposition and crossbench, passed by parliament on 11 June this year. Amendments included the mandatory registration of engineers.

Duty of care

The most significant change made by the DBP Act is the imposition of a statutory duty of care on any person who carries out construction work.

Construction work is defined to include: (1) building work; (2) the preparation of regulated designs and other designs for building work; (3) the manufacture or supply of a building product used for building work; and (4) supervising, coordinating, project managing or otherwise having substantive control over the carrying out of any of this work.

Practitioners involved in building design, building work, the manufacturing or supply of products used for building work and supervisory roles will be required to exercise reasonable care to avoid economic loss that would be caused by defects relating to, or arising from, construction work.

If a practitioner breaches this duty of care, a property owner will be entitled to damages (regardless of whether there is a contractual arrangement to carry out that construction work).

Application

The duty of care cannot be delegated or contracted out, and it does not limit damages or other compensation that may be available where a breach of another duty occurs.

The duty of care will apply retrospectively to existing buildings and contracts, if the economic loss has become apparent within the past ten years or after the DBP Act commenced. The duty of care also extends to subsequent owners.

Regulatory framework

The framework means that a principal certifier can only issue an occupation certificate after it has determined and obtained all compliance declarations for the building work. The compliance declarations can be only issued by registered practitioners at various levels of the building cycle.

Registration of practitioners

The DBP Act requires the registration and regulation of design and principal design practitioners, building practitioners, professional engineers and specialist practitioners.

The DBP Act broadly defines building practitioners to include anyone who is engaged, under a contract or other arrangement, to do building work or, if more than one person is doing the building work, the principal contractor for that work.

The broad nature of this definition means the vast majority of people engaged in building work will be required to register. Under the registration regime, building practitioners will be required to register with the Department of Customer Service and must be ‘adequately insured’ before undertaking building work.

Compliance declarations

The DBP Act introduces the following concepts to implement the registration and compliance framework:

• ‘building elements’ – which includes fire safety systems, waterproofing, load-bearing components, parts of a building enclosure and any other mechanical, plumbing or electrical services for a building to achieve compliance with the Building Code of Australia (BCA);

• ‘building work’ – defined broadly, it includes the construction, alteration, repair or renovation of a building or part of a building of a class or type prescribed by the regulations; and

• ‘regulated designs’ – which includes designs prepared for a building element for building work.

These new concepts facilitate a number of additional regulatory requirements, including requirements that:

• design and building practitioners must make ‘compliance declarations’ to the Department that building work or building elements that they have undertaken comply with the DBP Act and other required standards (including the BCA);

• any variations by a building practitioner from a regulated design for building elements or building works must be documented and new compliance declarations are sought from designers for the varied design; and

• when an application for an occupation certificate is made, notice must be given to registered building practitioners who have completed the work of the intention to apply for an occupation certificate.

Enhanced enforcement

In addition to the duty of care owed by the practitioners, the DBP Act also provides for enforcement through:

• disciplinary action against practitioners and companies involved in misconduct, including the imposition of fines between AU$550 and AU$330,0000, and imprisonment terms of up to two years for making a false compliance declaration or improper influence in relation to the issue of a compliance declaration;

• issuing of stop work orders, either unconditionally or subject to conditions; and

• executive liability for contraventions of the DBP Act, if they knowingly authorised or permitted the contravention.

The DBP Act also makes numerous references to a regulatory scheme that is yet to come into effect. The proposed regulations are anticipated to further detail:

• the insurance requirements;

• minimum qualification and continuing professional development requirements for practitioners;

• particulars required in regulated designs and compliance declarations and the form and manner in which these documents may be recorded and provided to the Department;

• additional offences as necessary to support the operation of the DBP Act; and

• the record keeping requirements for the Department and the Secretary in respect of documents collected under the Act.

Residential Apartment Buildings Act

The Act is designed to:

• ensure developers are prevented from carrying out building work that may result in serious defects or cause significant harm or loss to the public or present or future occupiers of the building; and

• require developers to notify the Secretary of the Department of Customer Service six to 12 months before applying for an occupation certificate, to enable the government to undertake quality assurance checks.

To achieve these objectives, the RAB Act enables the Secretary to:

• issue a stop work order if building work is being carried out, or is likely to be carried out, in a manner that could result in a significant harm or loss to the public or present or future occupiers of the building;

• issue prohibition orders stopping the issuing of an occupation certificate where notification requirements have not been met, there is a serious defect or payment of a full strata bond has not been made;

• issue a building work rectification order to require developers to repair defective building works; or

• prohibit the issuing of an occupation certificate in relation to building works in certain circumstances, including where a ‘serious defect’ exists.

Under the RAB Act, a new defect category of ‘serious defect’ has been established, which includes:

• non-compliant building elements that are attributable to a failure to comply with the BCA, relevant Australian standard or approved plans;

• a defective building element or building product that is attributable to defective design, defective or faulty workmanship or defective materials and is likely to cause an inability to inhabit or use the building, the destruction of the building or any part of it, or a threat of collapse of the building or any part of it;

• the use of a building product that is prohibited under the Building Products (Safety) Act 2017; and

• any other defects prescribed as a serious defect under the regulations.

Application

The RAB Act applies to ‘developers’, which is broadly defined by the Act to include:

• a person who contracted or arranged for, or facilitated or otherwise caused, the residential apartment building work to be carried out;

• if the residential building work is the construction of a building or part of a building, the owner of the land on which the work is carried out;

• the principal contractor for the work under the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 (NSW) (EPA Act); or

• in relation to work for a strata scheme, the developer of the strata scheme under the Strata Schemes Management Act 2015.

The RAB Act came into force on 1 September this year and applies to:

• ‘Class 2 buildings’ within the meaning of the BCA, which is limited to residential, multiresidential and mixed-use buildings;2 and

• all buildings either under construction or completed within the previous ten years, ensuring protections to owners of existing defective buildings.

Appeals

Developers can appeal stop work orders to the Land and Environment Court. However, this appeal must be lodged within 30 days of the notice of the order being given and, unless otherwise determined by the Court, will not operate to stay the stop work order.

Increased regulatory and enforcement powers

To ensure the integrity of the residential apartment building industry, the RAB Act grants the government a number of additional regulatory and enforcement powers including:

• requiring developers notify the Secretary of the Department at least six months, but not more than 12 months, before an application for an occupation certificate is intended to be made in relation to building works;

• allowing authorised officers to undertake inspections of notified building work;

• establishing penalties for the contravention of the requirements of the RAB Act, which range from infringements of $550 to $330,000;

• providing for the recovery of costs associated with compliance by a developer where there is more than one developer for the building work; and

• executive liability for contraventions of the RAB Act if they knowingly authorised or permitted the contravention.

It is intended that the Secretary’s powers under the RAB Act will be delegated to the Building Commissioner.

Implications

Overall, it is hoped that both the DBP and RAB Acts will have the desired effect of reinstating investor and community confidence in the construction industry, particularly Class 2 building work, without excessive time delays and cost as a consequence.

Developers and builders in NSW will need to have regard to these regulatory and governance requirements in projects going forward. There will be challenges for the design and building practitioners in particular, including ensuring they are adequately insured in a challenging professional indemnity insurance market.

Where developers have previously enjoyed a level of flexibility in relation to materials used or final designs, the new legislation will mean more rigour in the certification process and this will need to be factored into the whole planning and delivery project timeframe.

For existing and new projects, additional modifications to development consents may be required. Developers should consider the extent to which they are giving themselves sufficient flexibility where needed in documentation that will form part of consents and which will not fundamentally affect the design outcome.

It is difficult, at this stage, to foresee all of the potential implications of the RAB Act, but it does appear that there is a risk to developers of time and cost delays if vexatious claims are made regarding defective building works. Because of this, contingencies should be factored into development program timeframes, particularly for contentious projects.

Notes

1 Peter Shergold and Bronwyn Weir, Building Confidence (February 2018) www.industry.gov.au/sites/default/files/July%202018/document/pdf/building_ministers_forum_expert_assessment_-_building_confidence.pdf accessed 22 September 2020.

2 Exclusions for smaller class two projects that are low risk are expected to be included in the supporting regulations.

Italy

Simplifying Italian public tenders: will it work this time

Alessandro Paccione, Giada Russo, Marco Giustiniani and Giovanni Gigliotti, Rome

On 16 July this year, the Italian government enacted the so-called Simplifications Decree (Decree No 76/2020).

As the name reveals, the Decree is an attempt to simplify the legal system and, in particular, its administrative procedures and bureaucratic structures. Also, in light of the coronavirus pandemic and its impact on the economy, the government boosted its strategy of facilitating economic recovery through a massive simplification of administrative procedures and offices. More specifically, the Decree aims to provide citizens who are entitled to receive benefits from a public administration (eg, public contracts or building permits) with a faster and more efficient way to obtain them.

The scope of the Decree is wide, ranging from building to environmental law, including the green economy and, importantly for the public economy, public tenders.

Regulation on public tenders

Legislative Decree No 50/2016 (the ‘Public Contracts Code’) provides for the regulation of public tenders in Italy.

The Public Contracts Code executes and implements the European directives on public tenders by boosting public investments and providing a legal framework for the process to increase competition in the market.

Due to the high value of the investments and interests involved, public tenders require a balance between fast processes for awarding contracts that also respects the fundamental principles of legality and competition in the free market.

The economic crisis has required the government to tilt the scales towards the speed with which contracts are awarded in order to relaunch the national economy. In this context, the most impactful changes brought by the Simplifications Decree are empowering the contracting authorities to:

• directly award public contracts up to the value of €150,000;

• avoid prior publication of any call for tenders and use negotiated procedures for contracts with a value of €150,000 to €5m (in case of works) or €200,000 (in case of services and supplies, both the ‘EU thresholds’); and

• partially derogate some of the provisions within the Public Contracts Code in the case of ‘anti-crisis’ contracts.

These powers will cease on 31 July next year.

Public contracts up to €150,000

The contracting authorities may award any contract, the value of which is not higher than €150,000, without any competitive process or any prior consultation of private companies operating in the market. In essence the contracting authorities are entitled to choose private contractors at their discretion.1

The lack of competitiveness is intended to increase the speed with which the executor of a public contract is selected, even if simplifying the procedural steps to award a contract may result in works or services of a lower quality.

The power to use negotiated procedures

For contracts over €150,000 but lower than the EU thresholds, the contracting authorities may consult a number of operators (depending on the subject and the value of the contract) and then use the negotiated procedures without a prior call for tenders.

The negotiated procedures are extremely fast, allowing the contracting authorities to obtain works, services and supplies on conditions set out after negotiations conclude with a small number of selected private companies. Again, it is worth highlighting that the Simplification Decree permits contracting authorities to extend the range of procurements in which they may directly invite private operators to submit offers, without the filter of a call for tenders and with minimal competition, with a view to more efficient public procurements.

Anti-crisis contracts

The provision of the Decree that allows the contracting authorities to partially derogate the Public Contracts Code for anti-crisis contracts is potentially very invasive.

The speed at which anti-crisis contracts are awarded must be increased to face the consequences of the pandemic. These contracts are, for example, contracts for building (or restructuring) schools, universities, hospitals and public safety infrastructures in order to make them compliant with the Covid-19 safety measures. For these contracts, the public authorities may:

(1) use negotiated procedures without prior call for tenders (even if the amount is higher than the EU thresholds); and (2) more generally, derogate from any binding provision, except for criminal provisions and the general principles set out in the EU directives for public tenders.

Conclusion

According to its stated aim of boosting the economy, the Simplification Decree makes it easier for a company in Italy to be awarded a public contract through faster and more efficient procedures. Only its application will reveal if it has the desired economic effect without compromising the quality–price ratio in public works, services and supplies.

Notes

1 This power was previously limited to contracts with a value of up to €40,000.

Back to top