The EU’s Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive: what it means for the construction sector

Tuesday 6 May 2025

Credit: Gatot/Adobe Stock

Elise Edson

A&O Shearman, Paris

A turning point in European Union regulation

On 25 July 2024, the EU Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (‘CS3D’) entered into force. EU Member States now have two years (until 26 July 2026) to transpose it into their national laws. Compliance deadlines will be staggered, with the first group of companies expected to comply starting in July 2027.

The CS3D imposes a duty of due diligence on in-scope companies, requiring them to identify and address any adverse impacts on human rights and the environment arising from their activities, both inside and outside the EU. Companies are additionally required to adopt and put into effect a climate transition plan aligned with the Paris Agreement’s goal of limiting global warming to 1.5°C and the European Climate Law’s objective of achieving climate neutrality by 2050.

In the construction sector, the effects of the CS3D are expected to extend well beyond the larger firms directly subject to its requirements, impacting actors of all shapes and sizes across the construction supply chain. This overview highlights the CS3D’s implications for the sector and considers how the new rules could reshape industry practices.

Scope and compliance timelines

Earlier drafts of the CS3D incorporated an approach that designated the construction sector as a ‘high impact sector’, subjecting it to lower applicability thresholds. However, this approach was ultimately abandoned.

In the final text, the CS3D applies without distinction as to sector to:

- EU companies with 1,000+ employees and a net worldwide turnover of €450m+;

- non-EU companies with a net turnover in the EU of €450m+;

- franchises[1] with a net worldwide turnover of €80m+ and royalties in the EU of €22.5m+; and

- ultimate parent companies of a group of companies that meets these thresholds on a consolidated basis.

EU companies must comply within three to five years from the date of the CS3D’s entry into force (25 July 2024), depending on size, as follows:

- Group 1: 5,000+ employees and €1,500m+ net worldwide turnover: three years (2027);

- Group 2: 3,000+ employees and €900m+ net worldwide turnover: four years (2028); and

- Group 3: 1,000+ employees and €450m+ net worldwide turnover: five years (2029).

Non-EU companies will also have between three and five years to comply, as set out below:

- Group 1: turnover in the EU of €1,500m+: three years (2027);

- Group 2: turnover in the EU of €900m+: four years (2028); and

- Group 3: turnover in the EU of €450m+: five years (2029).

Franchises have five years (until 2029) to comply.

Companies not already covered by the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) must additionally publish an annual statement on their websites, including all relevant information on their performance of the duty of due diligence, starting for financial years on or after:

- Group 1 companies (as above): 1 January 2028; and

- Group 2 & 3 companies (as above) and franchises: 1 January 2029.

The duty of due diligence

Covered activities

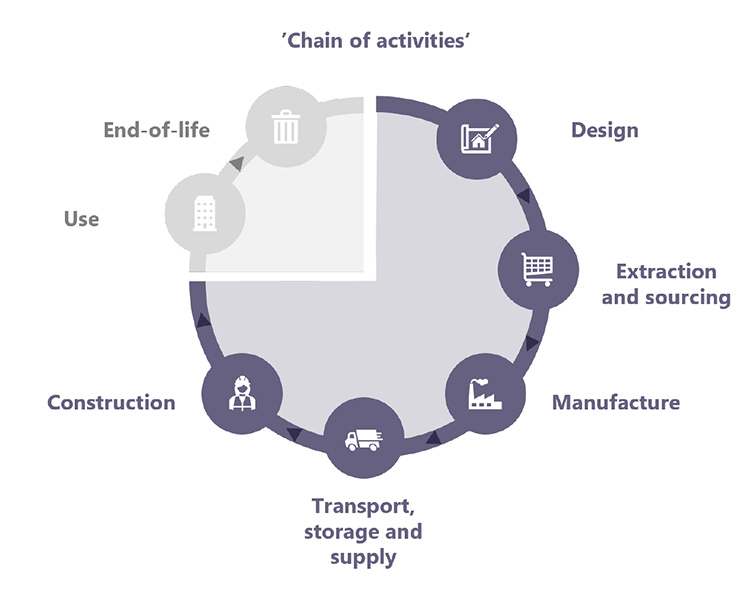

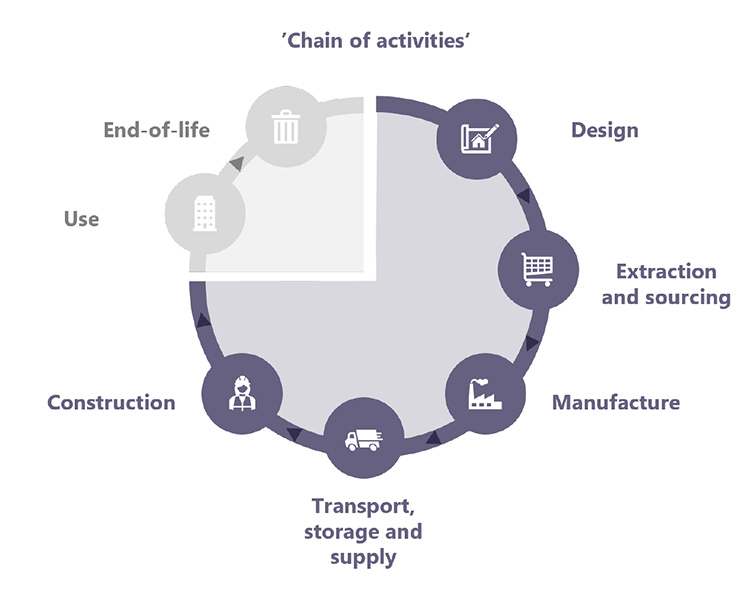

The duty of due diligence applies not only to a company’s own operations and those of its subsidiaries, but also extends across the company’s worldwide ‘chain of activities’, as defined in the CS3D, covering specific segments of the value chain.

In the context of a construction project, the definition of ‘chain of activities’ is broad enough to encompass critical upstream phases, including architecture and design, sourcing and manufacturing of construction materials, transport and logistics, and on-site construction. However, downstream activities related to the building’s use (eg, maintenance, repair and refurbishment), as well as end-of-life activities (eg, deconstruction or demolition, transport to disposal facilities, recycling or landfilling), are excluded from the definition.

The CS3D also provides that financial institutions are only subject to the due diligence obligations for their own operations, those of their subsidiaries and those of their upstream business partners. This means that financiers in the construction industry will not be held responsible under the CS3D for the impacts of the projects they finance.

Content of the duty

The duty of due diligence under the CS3D is modelled on existing international standards, including, in particular, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises on Responsible Business Conduct and the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (the ‘UN Guiding Principles’).

To fulfil their due diligence obligations:

- companies must integrate due diligence into policies and risk management systems;

- they must identify and assess potential and actual adverse impacts on human rights and the environment across their global chain of activities;

- they must prioritise adverse impacts by severity and likelihood where it is not feasible to address all of them at once. This risk-based approach allows companies to focus on addressing their most critical impacts first before turning to less urgent issues; and

- they must address adverse impacts by preventing or mitigating potential adverse impacts, and bringing to an end or minimising the extent of actual adverse impacts. This may entail developing and implementing action plans, seeking contractual assurances from business partners, making necessary investments, adapting business plans and strategies, providing training and capacity building. As a last resort, companies may have to suspend or terminate business relationships.

When addressing adverse impacts, companies should assess their level of involvement in the impact. They must take action to address potential or actual impacts they either (1) cause directly or (2) contribute to jointly with subsidiaries or business partners, including cases where the company facilitates or incentivises a business partner to cause the impact (excluding minor or trivial contributions). If a company is not directly or jointly responsible but is linked to the impact through a business partner, it should use its influence to address the harm. This may involve leveraging market power or linking business incentives to human rights and environmental performance.

The duty of due diligence extends across the company's worldwide 'chain of activities', covering specific segments of the value chain

- They must remediate actual impacts caused or contributed to by the company, this includes by providing financial or non-financial compensation to affected individuals. If the company is not directly or jointly responsible but is merely linked to the impact through a business partner, the company may provide voluntary remediation or use its influence to ensure that the business partner provides remediation.

- They must engage meaningfully with stakeholders throughout the due diligence process.

- They must provide a notification mechanism and complaints procedure.

- They must assess and monitor the adequacy and effectiveness of their due diligence measures at least every 12 months.

- They must communicate due diligence efforts and results in the form of an annual statement (unless already reporting under the CSRD).

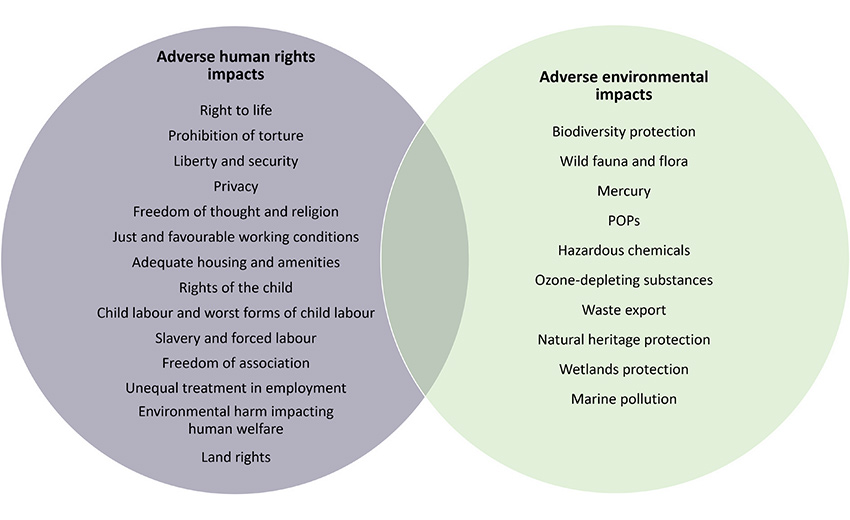

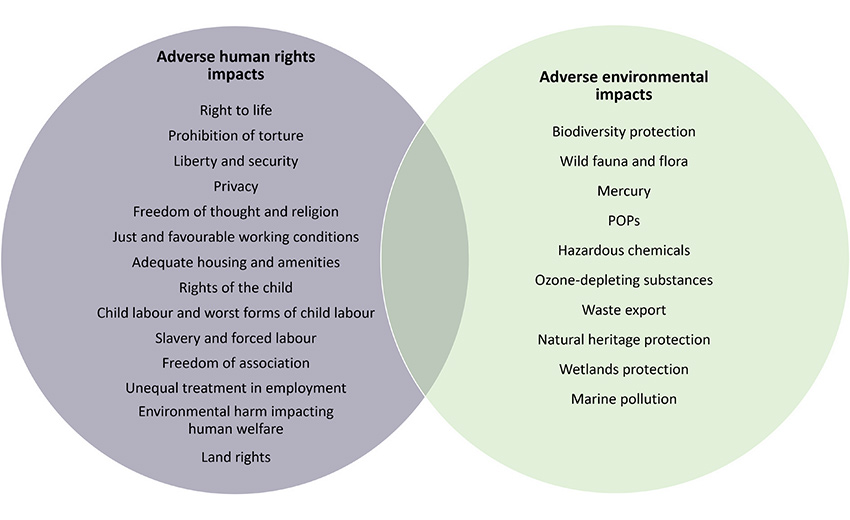

Adverse impacts

The covered adverse impacts are listed in annexes to the CS3D.

Adverse human rights impacts encompass violations of various enumerated rights and prohibitions found in international human rights instruments, as outlined below.

- Right to life includes the obligation to ensure, through proper training and oversight, that security personnel prevent harm or death.

- Prohibition of torture includes the responsibility to ensure, through proper training and oversight, that security personnel refrain from subjecting individuals to inhumane treatment.

- Liberty and security refers to the duty to ensure that employees are not unlawfully detained or subjected to physical violence or harassment.

- Privacy is the prohibition of arbitrary or unlawful interference with a person’s privacy, family, home or correspondence, and attacks on their honour or reputation.

- Freedom of thought and religion refers to the obligation to respect workers’ freedom of conscience and religious expression.

- Just and favourable working conditions include the duty to ensure that workers are provided with an adequate living wage, safe and healthy working conditions, and reasonable working hours.

- Adequate housing and amenities refers to the prohibition of limiting workers’ access to adequate housing, when provided by the company, and to essential needs like food, clothing, water and sanitation in the workplace.

- Rights of the child refers to the obligation to protect children’s health, education, basic needs and safety, and to prevent their exploitation or engagement in hazardous work.

- Child labour refers to the prohibition of employing children below the age required for compulsory schooling, and in any case, under 15 years old, with limited exceptions as permitted by local law.

- The worst forms of child labour refers to the prohibition of forced labour, trafficking, exploitation or hazardous work for all persons under the age of 18.

- Forced labour refers to the prohibition of any coerced work, including work under threat of penalty, debt bondage or human trafficking.

- Slavery refers to the prohibition of all forms of slavery or slavery-like practices, including severe economic or sexual exploitation.

- Freedom of association refers to the right of workers to form or join unions and engage in collective bargaining.

- Unequal treatment in employment refers to the prohibition of discriminatory practices in hiring, remuneration and promotions without legitimate justification.

The CS3D does not address the issue of conflicts between these international standards and local laws (eg, minimum wage laws, which may fall short of the CS3D’s requirement for an adequate living wage). The UN Guiding Principles stipulate that, in such cases, companies are expected to ‘[s]eek ways to honour the principles of internationally recognised human rights’ to the greatest extent possible in the circumstances.

Finally, recognising that environmental harm can result in violations of human rights, adverse human rights impacts also encompass breaches of certain environmental rights and prohibitions, as follows:

- environmental harm impacting human welfare refers to the prohibition of causing environmental degradation (eg, soil, water or air pollution) or other impacts on natural resources (eg, deforestation) compromising essential human needs, including access to food, clean water, sanitation, health and safety; and

- land rights refer to the right to protection against loss of livelihood, including the prohibition of unlawful eviction or loss of land and resources belonging to local communities. This requires companies, when acquiring land rights for projects, to verify whether the land is occupied or used by individuals, paying particular attention to marginalised or vulnerable groups.

Adverse environmental impacts include the following, implicating a wide range of construction activities and materials.

- Biodiversity protection refers to the obligation to avoid or minimise adverse impacts on biological diversity, in line with the Convention on Biological Diversity.

- Wild fauna and flora refer to the prohibition on trading specimens listed in the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora without a permit.

- Mercury refers to the prohibition on mercury-added products, the use of mercury in manufacturing and the unlawful treatment of mercury waste, in line with the Minamata Convention and EU regulations.

- POPs refers to the prohibition on the production, use and improper handling or disposal of substances listed in the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) and EU regulations.

- Hazardous chemicals refers to the prohibition on trading chemicals listed in the Rotterdam Convention.

- Ozone-depleting substances refers to the prohibition of the unlawful production, consumption and trade of ozone-depleting substances, in line with the Montreal Protocol.

- Waste export refers to the prohibition of hazardous and other waste export, in line with the Basel Convention and EU regulations.

- Natural heritage protection refers to the obligation to avoid or minimise adverse impacts on properties designated as natural heritage, in line with the World Heritage Convention.

- Wetlands protection refers to the obligation to avoid or minimise adverse impacts on wetlands, as defined by the Wetlands Convention.

- Marine pollution refers to the obligation to prevent marine pollution, including discharges from ships and dumping, in line with the Maritime Pollution (MARPOL) Convention and the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

Adverse human rights impacts encompass violations of various enumerated rights and prohibitions found in international human rights instruments

The duty to conduct environmental impact due diligence under the CS3D operates independently of, and in addition to, any national laws mandating Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) for certain construction projects, such as those under the EU’s EIA Directive. While EIAs typically focus on assessing and mitigating environmental impacts at a specific project site, the CS3D’s due diligence requirement has a broader scope, requiring companies to continuously assess and address environmental and human rights risks across their worldwide ‘chains of activities’.

The duty to adopt and implement a climate transition plan

In-scope companies not already subject to the CSRD must adopt and implement a climate transition plan to align, through best efforts, their business model and strategy with the transition to a net-zero economy.

The plan, which must be updated annually, should set time-bound targets for 2030 and every five years thereafter until 2050, covering scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions, as appropriate. For a construction project, scope 3 emissions notably encompass indirect emissions across the supply chain and project lifecycle. They include emissions from sourcing raw materials (aluminium (bauxite), copper, timber etc), manufacturing construction materials (cement, steel etc), transporting these materials to the construction site and end-of-life activities, such as demolition, recycling or landfilling.

The plan must additionally identify the company’s exposure to coal, oil and gas-related activities. In the construction sector, this would include any involvement in projects related to hydrocarbon infrastructure, such as those focused on the extraction, storage, transportation or use of fossil fuels.

In November 2024, the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG) released draft guidance for companies on designing climate transition plans. According to this draft, plans should, in addition to setting emissions reduction targets, include the following elements.

- Target compatibility describes how the company’s targets align with the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C target.

- Actions and decarbonisation levers provide an explanation of the specific measures and strategies the company will employ to meet its targets.

- Investment and funding refers to details of the investments and financial resources supporting the plan.

- EU Taxonomy alignment is a breakdown of the company’s activities that qualify as environmentally sustainable in accordance with the criteria imposed under the EU Taxonomy (see below).

- Progress reporting refers to updates on the plan’s implementation, assessing the effectiveness of actions taken and their contribution toward the company’s targets.

- Impacts, risks and opportunities (IROs) refers to disclosures on social and biodiversity-related IROs linked to the plan, covering effects on workers, communities and ecosystems.

Further iterations of the draft guidance are expected.

| The EU Taxonomy and the construction sector Activities covered by the EU Taxonomy notably include the construction of new buildings, renovation of existing buildings, and demolition and wrecking of buildings and other structures. For each activity, technical screening criteria are defined to determine whether the activity both makes a substantial contribution to at least one of six specified environmental objectives (‘substantial contribution criteria’), while doing no significant harm to any of the other objectives (‘do no significant harm criteria’). The six environmental objectives are: (1) climate change mitigation, (2) climate change adaptation, (3) sustainable use and protection of water and marine resources, (4) transition to a circular economy, (5) pollution prevention and control, and (6) protection and restoration of biodiversity and ecosystems. For example, to substantially contribute to climate change mitigation, a new building must have a primary energy demand at least ten per cent lower than the threshold set for nearly net-zero building requirements in line with the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive. To ensure that the building does no significant harm to the transition to a circular economy, at least 70 per cent (by weight) of non-hazardous construction and demolition waste must be prepared for reuse or recycling. Additionally, to be EU Taxonomy-aligned, the activity must adhere to certain minimum safeguards tied to human rights, bribery and corruption, taxation and fair competition. |

Enforcement and civil liability

Each Member State will designate supervisory authorities to enforce CS3D compliance. These authorities will have the power to issue injunctive orders and impose penalties, including fines of at least five per cent of the non-compliant company’s net worldwide turnover.

Companies may face civil liability in EU courts for breaching their CS3D due diligence obligations if they intentionally or negligently fail to prevent or mitigate potential adverse impacts, or fail to address actual adverse impacts. A company cannot, however, be held liable if the damage was solely caused by a business partner in its ‘chain of activities’, without any contribution from the company.

The duty of due diligence under the CS3D applies regardless of any contractual allocation of responsibility among stakeholders. Consequently, even if responsibility for specific aspects of the project, such as labour provision, or waste disposal, is assigned to the contractor, the owner remains accountable for fulfilling its due diligence obligations on these matters.

Impact on public procurement procedures

The CS3D provides that compliance with its provisions, whether mandatory or voluntary, qualifies as an environmental and/or social aspect that may, in line with the EU Public Procurement Directives (2014/23/EU, 2014/24/EU and 2014/25/EU), be factored into the award criteria for public and concession contracts, or imposed as a condition for the performance of such contracts. According to the CS3D’s recitals, non-compliant companies may also be excluded from public procurement procedures.

For construction companies, this means that aligning with the CS3D’s requirements could be a determining factor in securing or successfully performing public contracts or concessions. Failure to meet the relevant standards could also result in exclusion from future procurement opportunities.

Other ripple effects

Approximately 6,000 EU companies and 900 non-EU companies are estimated to meet the CS3D’s applicability thresholds. However, companies outside the CS3D’s immediate scope will still face indirect pressures arising from their business relationships with in-scope companies or entities connected to those in-scope companies through shared supply chains.

In the construction context, due diligence and climate transition plan-related requirements are likely to be increasingly integrated into project processes and contractual documentation, ensuring that human rights and environmental impacts are considered over the project’s lifecycle, starting from the planning and design phase.

For example, a key mechanism for companies to fulfil their due diligence obligations under the CS3D is contractual cascading. This process involves companies seeking contractual assurances from their direct business partners that they will comply with the applicable standards, and requiring these partners, in turn, to seek similar assurances from their own direct business partners, and so on, continuing the chain of accountability. Consequently, construction contracts may increasingly incorporate provisions requiring contractors to conduct human rights and environmental due diligence in accordance with the CS3D’s requirements, and to ensure that this obligation is passed on to subcontractors and suppliers.

As sustainability practices become more deeply embedded in regulations and industry standards, adhering to the CS3D will help companies stay ahead of fast-evolving requirements

The CS3D also mandates that companies verify compliance, which can be achieved through independent third-party verifications, or participation in industry or multi-stakeholder initiatives. Looking ahead, owners and contractors may insist on the right to impose penalties or sanctions for non-compliance, which could include fines, contract suspension or even termination. Additionally, they may reserve the right to withhold the approval of subcontractors who fail to meet specific sustainability standards.

These trends may, in turn, drive changes to standard form industry contracts, including the adoption of increasingly detailed human rights and environmental key performance indicators (KPIs), accompanied by monitoring and reporting obligations.

Additionally, the obligation to adopt and implement a climate transition plan will require many in-scope companies to significantly enhance the scope and quality of their emissions data. This will include gathering and reporting data from their suppliers. In the construction sector, subcontractors and suppliers may be asked to provide details on the carbon metrics of construction materials, transportation logistics or waste disposal practices. To ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information provided, they may be subject to audits or third-party verifications.

Conclusion

As outlined above, the CS3D will have a far-reaching impact on the industry, driving both in-scope companies and other stakeholders across the construction value chain to align with its requirements in order to stay competitive, maintain business relationships and qualify for public tenders within the EU.

Implementing the CS3D in the construction sector will present significant challenges due to the complexity of construction value chains and the number of actors involved. Stakeholders may operate across diverse regulatory frameworks, particularly on global infrastructure projects, making uniform compliance difficult. Smaller subcontractors and suppliers may lack the necessary resources or expertise to meet the CS3D’s stringent due diligence and climate reporting requirements. These requirements may not, moreover, always easily align with the sector’s traditional focus on delivering projects on time and within budget. The CS3D compels a fundamental shift in this regard, pushing companies to integrate human rights and environmental considerations at every stage of project planning and execution; an adjustment that may entail a steep learning curve for some.

Despite these challenges, the CS3D offers significant opportunities for the construction sector. As sustainability practices become more deeply embedded in regulations and industry standards across the EU and globally, adhering to the CS3D will help companies to stay ahead of fast-evolving requirements, minimising compliance and liability risks, while also building more resilient supply chains. In addition, embracing human rights and environmental due diligence can improve a company’s reputation, setting it apart in a competitive market, and better positioning it to meet the rising demand for sustainable buildings and infrastructure.

[1] This means a company that has entered into, or is the ultimate parent company of a group that has entered into, franchising or licensing agreements within the EU in return for royalties, where these agreements ensure a common identity, a common business concept and the application of uniform business methods.

Elise Edson is a counsel at A&O Shearman in Paris and can be contacted at elise.edson@aoshearman.com. |