Unforeseen circumstances and contract rebalancing – August 2025

Friday 29 August 2025

Thomas Frad

KWR, Vienna

Douglas Stuart Oles

Smith Currie Oles, Seattle

Richard Bailey

Druces, London

Yann Schneller

DARCI, Paris

Claus H Lenz

Lenz Dispute Resolution, Hamburg

Emma Niemistö

Borenius, Helsinki

Arianna Perotti

Dardani Studio Legale, Milan

Although construction contracts are generally based on predictions as to the costs and time required to perform various tasks, the parties’ terms must sometimes be rebalanced to adjust for unforeseen circumstances that are encountered. In this article, authors from seven countries compare how such unforeseen circumstances are handled in their respective jurisdictions, including analysis under both common law and civil law systems. This is the second of two parts; the first part was published in the preceding issue of this journal.

Government changes in law

Although there are still relatively few places where construction work is directly interrupted by wars or civil unrest, those events and other political developments can have widespread indirect impacts on the costs of the progress of construction.

Following the Russian invasion of the Ukraine, a number of (mostly Western) governments implemented embargoes against Russian commerce, and there was a concerted effort in a number of countries to reduce consumption of Russian natural gas. Government actions have also been used to freeze foreign assets and to restrict access to the international banking system.

In the United States and elsewhere, government tariffs, duties and other import taxes have been imposed on foreign products in retaliation for perceived unfair trade practices or to protest actions of foreign governments. Because the construction industry operates in a global marketplace (especially with regard to purchases of major materials like steel and aluminium), the unexpected imposition of embargoes, tariffs and increased customs duties can have significant impacts on the costs of construction.

Embargoes, tariffs, customs duties, increased taxes and new restrictive regulations are all obviously acts of government that can be characterised as changes in law. In many construction contracts, changes of law (if they were not known or foreseen at the time of contracting) are identified as a basis for compensating the contractor under a variation or change order.

Example

World Bank sample clause (from PPP in Infrastructure Center for Contracts, Law and Regulations):

If the Contractor suffers (or will suffer) delay and/or incurs additional costs as a result of a Change of Law [and the net cost to the Contractor is in excess of [ ] as a result of a Change of Law], then the Contractor will be entitled to an adjustment to the [contract price/tariffs] and/or an extension of time. The Contractor must deliver a notice to the Authority [within [] weeks/months of the occurrence of that Change of Law] identifying the Change of Law and the impact of that change of Law,[accompanied by full details of the claim]. The Authority will proceed in accordance with the Determination Procedure to agree or determine these matters.

FIDIC contracts

The 1999 and 2017 editions of the FIDIC Red, Yellow and Silver Books all contain provisions entitling a contractor to additional time and costs incurred as a result of a change in law taking effect after the base date. Measures such as embargoes, tariffs, customs, duties, increased taxes and new restrictive regulations are covered by this clause and would generally entitle a contractor to additional time and cost incurred, to the extent that such changes in laws were implemented in the country where the works are performed.

In the 1999 edition of the FIDIC rainbow suite, the change in law provision is drafted in identical terms across the three books (with one minor difference: the Silver Book refers to the ‘Employer’ rather than the ‘Engineer’). Sub-Clause 13.7 [Adjustment for Changes in Legislation] provides that:

‘The Contract Price shall be adjusted to take account of any increase or decrease in Cost resulting from a change in the Laws of the Country (including the introduction of new Laws and the repeal or modification of existing Laws) or in the judicial or official governmental interpretation of such Laws, made after the Base Date, which affect the Contractor in the performance of obligations under the Contract.

If the Contractor suffers (or will suffer) delay and/or incurs (or will incur) additional Cost as a result of these changes in the Laws or in such interpretations, made after the Base Date, the Contractor shall give notice to the Engineer and shall be entitled subject to Sub-Clause 20.1 [Contractor’s Claims] to:

(a) an extension of time for any such delay, if completion is or will be delayed, under Sub-Clause 8.4 [Extension of Time for Completion], and

(b) payment of any such Cost, which shall be included in the Contract Price.

After receiving this notice, the Engineer shall proceed in accordance with Sub- Clause 3.5 [Determinations] to agree or determine these matters.’

Because the construction industry operates in a global marketplace (…) the unexpected imposition of embargoes, tariffs and increased customs duties can have significant impacts.

The ‘Base Date’ is defined as the date 28 days prior to the latest date for submission of the tender (Sub-Clause 1.1.3.1 of the 1999 edition of the FIDIC Red, Yellow and Silver Books). The definition of ‘Laws’ is broad, encompassing ‘all national (or state) legislation, statutes, ordinances and other laws, and regulations and by-laws of any legally constituted public authority’. (Sub-Clause 1.1.6.5 of the 1999 edition of the FIDIC Red, Yellow and Silver Books).

In the 2017 edition of the FIDIC rainbow suite, the change in law provision is now found in Sub-Clause 13.6 [Adjustments for Changes in Laws]. This clause is significantly longer than its 1999 equivalent but retains the same core principles: a contractor may be entitled to time and cost as a result of a change in law introduced after the base date. However, the definition of changes in law is broader, as it now includes changes in permits, permissions and licences. In this respect it is more favourable to contractors. Yet, in contrast to the 1999 edition, the employer is now entitled to a reduction in the contract price if the change in law results in a decrease in ‘Cost’. Sub-Clause 13.6 [Adjustments for Changes in Laws], which is identical across the three books (with the minor exception that the Silver Book refers to the ‘Employer’ and not the ‘Engineer’), states that:

‘Subject to the following provisions of this Sub-Clause, the Contract Price shall be adjusted to take account of any increase or decrease in Cost resulting from a change in:

(a) the Laws of the Country (including the introduction of new Laws and the repeal or modification of existing Laws);

(b) the judicial or official governmental interpretation or implementation of the Laws referred to in sub-paragraph (a) above;

(c) any permit, permission, license or approval obtained by the Employer or the Contractor under sub-paragraph (a) or (b), respectively, of Sub-Clause 1.13 [Compliance with Laws]; or

(d) the requirements for any permit, permission, licence and/or approval to be obtained by the Contractor under sub-paragraph (b) of Sub-Clause 1.13 [Compliance with Laws], made and/or officially published after the Base Date, which affect the Contractor in the performance of obligations under the Contract. In this Sub-Clause ‘change in Laws’ means any of the changes under sub-paragraphs (a), (b), (c) and/or (d) above. If the Contractor suffers delay and/or incurs an increase in Cost as a result of any change in Laws, the Contractor shall be entitled subject to Sub-Clause 20.2 [Claims For Payment and/or EOT] to EOT and/or payment of such Cost.

If there is a decrease in Cost as a result of any change in Laws, the Employer shall be entitled subject to Sub-Clause 20.2 [Claims For Payment and/or EOT] to a reduction in the Contract Price.

If any adjustment to the execution of the Works becomes necessary as a result of any change in Laws:

(i) the Contractor shall promptly give a Notice to the Engineer, or

(ii) the Engineer shall promptly give a Notice to the Contractor (with detailed supporting particulars).

Thereafter, the Engineer shall either instruct a Variation under Sub-Clause 13.3.1 [Variation by Instruction] or request a proposal under Sub-Clause 13.3.2 [Variation by Request for Proposal].’

The ‘Base Date’ remains defined as the date 28 days prior to the latest date for submission of the tender (Sub-Clause 1.1.4 of the 2017 edition of the FIDIC Red and Yellow Books, and Sub-Clause 1.1.2 of the 2017 edition of the Silver Book).

The definition of ‘Laws’ is broader than in the 1999 definition, now encompassing ‘all national (or state) legislation, statutes, acts, decrees, rules, ordinances, orders, treaties, international law and other laws, and regulations and by-laws of any legally constituted public authority’. (Sub-Clause 1.1.49 of the 2017 edition of the FIDIC Red and Yellow Books, and Sub-Clause 1.1.43 of the 2017 edition of the Silver Book).

Italy

In Italy, the risk of changes in law is usually allocated in the contract. Different scenarios could apply, depending on the type and location of construction and on the different stakeholders. With regard to embargoes and new restrictive regulations, under the Italian Civil Code, the unforeseeable changes of law rendering the contractual execution impossible or against law, are a so-called factum principis, which:

• exempts the debtor from duty to perform the contract and from liability in respect thereof;

• determines the extinguishment of the obligation and of the contractual termination.[1]

In this connection, on occasion of the past conflict in Kuwait, the Court of Genoa stated that contracts under which Italian companies undertook to construct warships for the Government of Iraq were considered terminated due to the practical impossibility of their performance. They were rendered impossible because of the embargo imposed by the United Nations and the Italian Government during the Iran–Iraq conflict.[2]

In the event that unforeseeable and mandatory changes in law enacted after the contract execution materially impact performance of a contract scope, a variation could be regarded as a necessary remedy. If the contract fails to provide for this remedy, the contractor may be obliged to implement the required variation for a price not exceeding one-sixth of the overall agreed price. If this threshold is exceeded, the Contractor can withdraw from the contract and is entitled to receive equitable compensation. Similarly, the employer may be entitled to withdraw from the contract if an unexpected change in law would require paying the contractor large equitable compensation.[3]

Germany

In Germany, unexpected changes in laws and regulations can reach the level of interference with the basis of a transaction as addressed in section 313 of the German Civil Code. The same principles apply as described above under Italian law. It may, however, be unnecessary to modify the contract if the change in the law already provides regulations that will maintain a proper balance of interests under existing contracts.[4]

Changes in tax laws in principle do not qualify as an event that invokes section 313 unless specific tax regulations and their effects are clearly identified in a contract as essential underlying terms.

However, in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, where businesses were ordered to close by public authorities, German courts have granted a right to request a modification in rent to be paid whereby compensation from and interests of the landlord have to be fairly considered.[5]

Austria

There is no general provision in Austrian civil law that assigns the risk of changes in the law to a party. However, amendments to Austrian law typically contain transitional provisions and clauses governing the implementation of a new regulation. From these rules, it can often be determined in individual cases who bears the risk of the new regulation. If there is no such provision, the rules of the sphere theory already described above apply in the area of contract law. Legislative changes fall within the ‘neutral sphere’, where the contractor generally bears the risk.

ÖNORM B 2110 also contains no general provision that assigns the risk of a change in standards, whether of a legal or technical nature, to a party. However, ÖNORM B2110 does contain various provisions that assign individual risks of a change in legal provisions to a party. These provisions are outlined below.

If the statutory provisions on VAT change during the term of a contract, the VAT is to be reimbursed at the newly resulting rate (clause 6.3.1.3). The ÖNORM orders that the VAT is to be paid by the employer in the statutory rate applicable at the time.

The employer is also generally responsible for obtaining the necessary permits and official approvals for the construction work (clause 5.4.1). If a change in this connection occurs during the construction project, the risk is borne by the employer.

In contrast, the contractor shall obtain the necessary permits and official approvals required for the performance of its services (section 5.4.2). Therefore, the contractor bears the risk for these permits. Interestingly, however, ÖNORM B2110 states that the contractor is not required to obtain any permits if these have already been obtained by the employer (clause 5.4.2), so that the employer also assumes the risk of change in this area.

Technical performance specifications regularly refer to technical ÖNORM standards, and it is agreed that the contractor must comply with these standards when providing the services. In this context, ÖNORM B 2110 stipulates that the version valid at the time of the commencement of the offer period shall apply. If there is no defined offer period, the date of the offer shall apply (clause 5.1.2). If such a technical ÖNORM is amended during execution, the employer shall decide whether to order a change in performance. If an employer orders such a change, it must generally compensate the contractor for the resulting additional costs.

Legislative changes could also potentially lead to the annulment or adjustment of a contract due to the cessation or modification of the contractual basis. According to the case law, however, a change in legal circumstances only very rarely leads to a party being able to challenge the contract on the grounds that the basis of the contract has ceased to exist.[6]

Finland

In Finland, there is no statutory legislation that allocates the risk of changes in law affecting a construction contract. Under local general conditions in YSE 1998, however, there is a provision addressing changes in costs caused by state legislative measures – see paragraph 3 in the below section 49:

Section 49 Effect of change in prices and wages on contract price

1. Unless otherwise specifically stated in the contract, changes in the level of prices and wages shall not increase or decrease the contract price.

2. Value added tax is calculated on the contract price as the actual tax payable at the time in question.

3. Unless otherwise stated in the contract, changes in costs caused by state legislative measures (act, decree, decision of the Council of State or a ministerial decision), other than those referred to in paragraph 2, shall be taken into account as a factor increasing or decreasing the contract price only if their combined effect is at least 0.5 per cent of the contract price exclusive of value added tax. Taking such cost changes into account also requires that

– their justification arose after submission of the tender leading to the contract or, in other cases, after signing of the contract,

– they could not have been taken into account in preparing the tender or, likewise, in drawing up the contract, and

– they have a direct effect on the building contract work covered by the contract.

In England (...) If the change takes effect before the contract is signed (…) then the parties are generally bound by the terms of the contract.

4. Demands concerning changes in costs must be presented with their justifications no later than the time of the contract inspection under §70 or §71. By providing the relevant receipts or using any other reliable method, the contractor must notify the client of the information necessary for calculating the changes in cost.

5. Neither party, however, shall have the right to a change in the contract price under paragraph 3 with the said justification in so far as the change that may be compensated on the basis of the index clause of the contactor would be in excess of what is permitted by the legislation in force at the given time. If such a change in cost occurs at the end of the building contract period, the contracting party responsible for the delay shall not be entitled, on the basis of these provisions, to demand an increase or decrease in the contract price in his favour.

The above section 49 has been invoked by many contractors claiming that European Union sanctions against Russia, being comparable to Finnish state legislative measures under paragraph 3, would allow them to claim compensation for the resulting price increases. However, this is not the intended application scenario for this specific YSE 1998 term, and accepting such logic would effectively change the prevailing notion that contractors should generally bear the risk of price changes (this main rule being stated in paragraph 1). The general notion is thus to deny claims for cost increases based on the Ukraine war and EU sanctions based on YSE 1998 section 49, but that position is yet to be tested in Finnish courts.

England

In England virtually all construction works are carried out under a contract, and works of substantial value are usually performed under a JCT or NEC contract. The standard form contracts take different approaches to changes in law after the contract is signed. If the change takes effect before the contract is signed, even if the works have commenced before the change of law, then the parties are generally bound by the terms of the contract they signed up to.

In the case of NEC there is an optional clause X2 ‘Changes in Law’ which states:

X2.1 A change in the law of the country in which the Site is located is a compensation event if it occurs after the Contract Date. If the effect of a compensation event which is a change in the law is to reduce the total Defined Cost, the Prices are reduced.

This clause must be actively selected when completing the contract otherwise there is no right to a compensation event for changes in law.

The position under the JCT contract form is different, continuing the example of the JCT DB form.

France

French private law does not contain any mechanism that guarantees compensation for an unforeseen change in law. This matter is therefore left to negotiation between the parties. The two main standard forms of private construction contracts in France have adopted different approaches to changes in law. NF P 03-001 for private building works provides that a contractor is entitled to compensation for costs incurred due to changes in laws or regulations that increase the costs of the performance of the works and that are not covered by the price variation clause (Article 9.3); whereas NF P 03-002 for civil engineering works limits a contractor’s entitlement to additional costs incurred only for changes in VAT and similar taxes applicable to invoicing (Article 9.3). Prudent contractors would therefore be well advised to expand the scope of the change in law provisions in NF P 03-002 through the particular conditions.

Under French administrative law, the theory of fait du prince (literally, act of the prince) provides that a contractor must be compensated for any action or measure taken by a public body in its public capacity that: (1) was unforeseeable when the contract was signed and (2) makes performance of the contract more onerous. However, one key limitation is that it applies only if the measure or action was taken by a public legal entity that is the contracting party.

The standard form of contract for public works in France (Cahier des Clauses Administratives Générales – CCAG. – Marchés publics de travaux, last published in 2021) provides that in the event of unforeseen changes in legislations or regulations which increase the cost of performing the contract, the parties shall meet to assess the financial impact of the change and, if necessary, formalise an amendment to implement the required changes (Article 9.1.1).

Changes in the market pricing

In construction, as in other industries, long periods of stable prices tend to reduce focus on allocating the risk of market price fluctuations that affect labour and materials. As the world emerged from the disruptions of the Covid-19 epidemic and the massive deficit spending by governments that was intended to maintain market stability, the industrialised world sustained a surge of inflation and increased price volatility among contractors and suppliers who were attempting to handle (or take advantage of) asymmetrical surges in demand.

If labour pricing is uncontrolled, contractors can be exposed to the risk of labour cost escalation which can generate substantial losses in a time of unusual inflation. When workers experience substantial increases in their own costs of living, it is not surprising that they press for wage increases, and construction projects are exposed to the risks of strikes and other labour disruptions while those demands are being resolved.

One remedy on large multi-year unionised projects is to stabilise prices through a project labour agreement that establishes hourly rates and benefits to remain in effect throughout the life of the job. Another approach is for a contract to allow for periodical labour escalation adjustments (eg, annually) which can be tied to a published price index and/or capped at a maximum percentage of increase per year.

With regard to materials, pricing can vary due to a variety of factors other than acts of government. As noted earlier, an event like the Covid-19 epidemic can severely disrupt supply and demand factors, leading to shortages and spikes in key materials like steel, aluminium and cement. Sudden market price variations can also arise directly or indirectly from wars, civil unrest and other government acts.

In the past, unexpected price volatility for materials has primarily been a contractor risk, but recent events have created pressures to modify this approach. On many jobs, the practical reality is that key material suppliers will not guarantee prices for longer than 30 or 60 days, and contractors are unwilling and/or unable to bear the risks of substantial price fluctuations occurring later on a long-term project.

In the past, unexpected price volatility for materials has primarily been a contractor risk, but recent events have created pressures to modify this approach.

One possible remedy is for the employer or contractor to pre-purchase sufficient materials for a job at the outset and thereby avoid exposure to long-term price fluctuations. Another remedy is for contracts to allow a price variation for documented material price increases above the prices reasonably assumed at the time a job was bid. A third approach might be to establish a contract contingency fund that can be used for unexpected material price fluctuations (sharing any unused contingency between the parties so as to incentivise cost savings).

FIDIC contracts

The 1999 and 2017 editions of the Red and Yellow Books contain a price revision clause. The 1999 and 2017 editions of the Silver Book, however, do not contain such a clause, as these forms place greater risk on the Contractor.

Sub-Clause 13.8 [Adjustment for Changes in Cost] of the 1999 edition of the FIDIC Red and Yellow Books provides that:

‘In this Sub-Clause, “table of adjustment data” means the completed table of adjustment data included in the Appendix to Tender. If there is no such table of adjustment data, this Sub-Clause shall not apply.

If this Sub-Clause applies, the amounts payable to the Contractor shall be adjusted for rises or falls in the cost of labour, Goods and other inputs to the Works, by the addition or deduction of the amounts determined by the formulae prescribed in this Sub-Clause. To the extent that full compensation for any rise or fall in Costs is not covered by the provisions of this or other Clauses, the Accepted Contract Amount shall be deemed to have included amounts to cover the contingency of other rises and falls in costs.

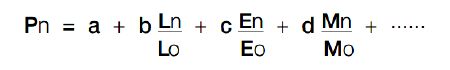

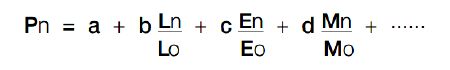

The adjustment to be applied to the amount otherwise payable to the Contractor, as valued in accordance with the appropriate Schedule and certified in Payment Certificates, shall be determined from formulae for each of the currencies in which the Contract Price is payable. No adjustment is to be applied to work valued on the basis of Cost or current prices. The formulae shall be of the following general type:

where:

‘Pn’ is the adjustment multiplier to be applied to the estimated contract value in the relevant currency of the work carried out in period ‘n’, this period being a month unless otherwise stated in the Appendix to Tender;

‘a’ is a fixed coefficient, stated in the relevant table of adjustment data, representing the non-adjustable portion in contractual payments;

‘b’, ‘c’, ‘d’, … are coefficients representing the estimated proportion of each cost element related to the execution of the Works, as stated in the relevant table of adjustment data; such tabulated cost elements may be indicative of resources such as labour, equipment and materials;

‘Ln’, ‘En’, ‘Mn’, … are the current cost indices or reference prices for period ‘n’, expressed in the relevant currency of payment, each of which is applicable to the relevant tabulated cost element on the date 49 days prior to the last day of the period (to which the particular Payment Certificate relates); and

‘Lo’, ‘Eo’, ‘Mo’, … are the base cost indices or reference prices, expressed in the relevant currency of payment, each of which is applicable to the relevant tabulated cost element on the Base Date.

The cost indices or reference prices stated in the table of adjustment data shall be used. If their source is in doubt, it shall be determined by the Engineer. For this purpose, reference shall be made to the values of the indices at stated dates (quoted in the fourth and fifth columns respectively of the table) for the purposes of clarification of the source; although these dates (and thus these values) may not correspond to the base cost indices.

In cases where the “currency of index” (stated in the table) is not the relevant currency of payment, each index shall be converted into the relevant currency of payment at the selling rate, established by the central bank of the Country, of this relevant currency on the above date for which the index is required to be applicable.

Until such time as each current cost index is available, the Engineer shall determine a provisional index for the issue of Interim Payment Certificates. When a current cost index is available, the adjustment shall be recalculated accordingly.

If the Contractor fails to complete the Works within the Time for Completion, adjustment of prices thereafter shall be made using either (i) each index or price applicable on the date 49 days prior to the expiry of the Time for Completion of the Works, or (ii) the current index or price: whichever is more favourable to the Employer.

The weightings (coefficients) for each of the factors of cost stated in the table(s) of adjustment data shall only be adjusted if they have been rendered unreasonable, unbalanced or inapplicable, as a result of Variations.’

Sub-Clause 13.7 [Adjustment for Changes in Cost] of the 2017 edition of the FIDIC Red and Yellow Books provides that:

‘If Schedule(s) of cost indexation are not included in the Contract, this Sub-Clause shall not apply.

The amounts payable to the Contractor shall be adjusted for rises or falls in the cost of labour, Goods and other inputs to the Works, by the addition or deduction of the amounts calculated in accordance with the Schedule(s) of cost indexation. To the extent that full compensation for any rise or fall in Costs is not covered by this Sub-Clause or other Clauses of these Conditions, the Accepted Contract Amount shall be deemed to have included amounts to cover the contingency of other rises and falls in costs.

The adjustment to be applied to the amount otherwise payable to the Contractor, as certified in Payment Certificates, shall be calculated for each of the currencies in which the Contract Price is payable. No adjustment shall be applied to work valued on the basis of Cost or current prices.

Until such time as each current cost index is available, the Engineer shall use a provisional index for the issue of Interim Payment Certificates. When a current cost index is available, the adjustment shall be recalculated accordingly.

If the Contractor fails to complete the Works within the Time for Completion, adjustment of prices thereafter shall be made using either:

(a) each index or price applicable on the date 49 days before the expiry of the Time for Completion of the Works; or

(b) the current index or price

whichever is more favourable to the Employer.’

Under Sub-Clause 13.8 of the 1999 edition of the FIDIC Red and Yellow Books and Sub-Clause 13.7 of the 2017 edition of the FIDIC Red and Yellow Books, the employer may bear some of the risk of increased cost of goods and labour.

However, the extent to which the employer bears the risk of inflation depends on negotiations between the parties and, more specifically, the price indices and coefficients included in the table of adjustment data in the Appendix to Tender (in the 1999 form), or in the Schedule(s) of cost indexation (in the 2017 form).

In other words, there is no guarantee that the actual inflation suffered by a contractor will be fully covered by applying the FIDIC price adjustment formula. The contract price will only increase to the extent allowed by the formula. As a result, recent projects have shown that contractors often recover only a fraction of their additional costs incurred due to inflation.

Furthermore, the non-recovered inflation costs remain a contractor risk, owing to the specific language of the second paragraph of Sub-Clause 13.8 of the 1999 edition of the Red and Yellow books, and the fourth paragraph of Sub-Clause 13.7 of the 2017 edition of the Red and Yellow books (as reproduced above).

However, despite these contractual limitations, as discussed below, some remedies may be available under the applicable law, such as the hardship theory under French private and administrative law.

Italy

In Italy the risk of unexpected excessive price volatility affecting construction contracts is specifically addressed in the Civil Code, which allows a price adjustment if, as a result of unforeseeable circumstances, an increase or decrease in the cost of the materials or labour causes an increase or decrease of more than one-tenth of the total price agreed upon.[7]

This rule of law can be waived by the parties and, in the past, such waiver was a common practice. However, the drastic market price fluctuations experienced in the last few years as a consequence of the pandemic and the Ukraine war, have put the price volatility and possible remedies in the limelight.[8] Nowadays the inclusion of automatic price adjustment clauses has become the norm not only in private projects but also in public tenders.

The new Italian Public Contracts Code established the inclusion in tender documents of a price revision clause mandatorily applicable upon the occurrence of particular conditions of an objective nature, unforeseeable at the time of the contract tender.[9]

Germany

In Germany price increases are generally considered to be a risk of the contractor. For example, price increases for steel in the early 2000s were not considered as events interfering with the basis of the transaction.

However, the latest price increases arising from the Ukraine war and the recent abnormal inflation have led to ministerial regulations and may change the prevailing practice.

There are no fixed limits, but some commentaries propose that price increases between 20 to 25 per cent might be an appropriate threshold for contract price adjustments. Some even want to see the threshold as low as 15 per cent, but this would apply not to a single item of material but to the total volume of the contract price.

It is recommended to include price escalation clauses in offers and in contracts.[10]

Austria

In principle, a contractor bears the risk of price increases for goods or services that it procures. However, price reductions also benefit the contractor. This is in the nature of a fixed price arrangement.

In contrast, ÖNORM B 2110 stipulates in clause 6.3.1.1 that a fixed price only applies to services that are to be completed according to the contract within six months after the end of the bidding period. For services to be performed thereafter, variable prices apply. Variable prices can be determined under ÖNORM B 2111, which is based on various price indices (eg, wages) to protect against inflationary changes. Therefore, according to these provisions, a contractor in Austria generally bears the risk of inflation only for six months, after which prices are adjusted according to a transparent procedure with published indices for the construction industry. In practice, the generally applicable consumer price index can also be used instead of specialised construction cost indices.

Theoretically, it would also be conceivable to rely on the cessation of the basis of the contract, but this approach is regularly rejected by Austrian courts. However, in extreme circumstances, where the fulfilment of the contract would result in a financially unsustainable situation endangering one party’s existence, it could be argued based on this premise.

Finland

In Finland, the contractor would traditionally be considered to bear the risk of price increases for goods or services that it procures.

Contract provisions establishing a right to a price increase would have to be specifically agreed upon in writing. The YSE 1998 general conditions section 48 sets out a general framework for adjustments in case the parties have agreed to apply some kind of price indexation. It is indeed becoming more and more common for contractors to require at least certain crucial procurement packages within their scope to be indexed (either by consumer price index or specialised construction cost indices).

In very extreme cases, where a party can prove a wholly unforeseeable price increase that would result in the contract being economically unsustainable, one could argue that the pricing should be adjusted based on section 36 of the Finnish Contracts Act as discussed above.

During the first months of the Ukraine war, there were cases where construction contract negotiations stalled, and some employers agreed to include clauses giving comfort to contractors whose procurement market pricing was significantly affected by the EU sanction effects. In some of those cases, parties could agree to indexation of key purchases, or even adopting a cost-plus contracting form for some procurement packages. Some parties also negotiated an employer risk contingency fund, and incentivised risk sharing based on certain target costs while allowing demonstrable price variations to be compensated to contractors.

England

In England the general position is that where a contract is for a fixed price then the risk of cost increases is a contractor risk. Where the contract form is a cost reimbursable contract, however, then the risk of cost increases is an employer risk.

Even in a fixed price contract, which the JCT Design and Build Contract is generally perceived to be, there are provisions for price adjustments when there has been a change in the nature of the works. Generally, the JCT DB form includes three options to deal with price fluctuations, Options A, B and C. Option A is the default position and the only one in the printed forms. A brief summary of the Options is as follows:

• Option A – deals with contribution, levy and taxes paid by the employer.

• Option B – labour and materials cost and tax fluctuation.[11]

• Option C – Formula adjustment based on a detailed provision for the calculation of the loss. This also includes provisions for fluctuations in the price of articles manufactured outside of the United Kingdom.

Generally, these fluctuation provisions, while an option in the unamended contract, are a risk that most employers will not accept. In the present climate of uncertainty, more contractors are insisting on fluctuations being reinstated into contracts.

France

French private law does not contain any default price revision principle. Furthermore, historically the doctrine of hardship was not recognised under French private law. However, the 2016 reform of the French Civil Code introduced a new Article 1995, which formally recognises the doctrine of hardship in French private law. Under Article 1995 of the French Civil Code, hardship creates a right to renegotiate a contract upon the occurrence of circumstances:

• which were not foreseeable when the contract was entered into;

• which make the performance of the contract excessively onerous for a party; and

• where the risk of such onerous performance was not assumed by that party.

If the other party refuses to renegotiate or renegotiations fail, a court may, at the request of a party, revise or terminate the contract.

However, Article 1195 is not mandatory law, meaning it can be excluded by contract. In this respect, French Courts hold that if a contract has a lump-sum fixed price, the parties are considered to have waived the benefit of Article 1195.[12] If a contract contains a price revision clause (such as Sub-Clause 13.8 [Adjustments for Changes in Cost] of the 1999 edition of the Red and Yellow Books or Sub-Clause 13.7 [Adjustments for Changes in Cost] of the 2017 edition of the Red and Yellow Books), a French judge will likely consider that the contractor has assumed the risk of inflation beyond the price adjustment formula, as these provisions expressly indicate.

The Paris Commercial Court judgment dated 14 December 2022[13] illustrates how French judges can use their power under Article 1195 of the French Civil Code in the context of the inflation of goods or materials. A supplier of ceramic tiles argued that, as of 2020, the Covid-19 outbreak followed by the war in Ukraine increased its production costs, justifying the renegotiation of the contract prices. However, renegotiation failed. The supplier therefore asked the court to revise the contract price or, alternatively, terminate the contract. The Commercial Court found that the conditions of hardship pursuant to Article 1195 of the French Civil Code were met, however, it considered the supplier’s requested price revision was not justified and therefore, decided to terminate the contract. This case illustrates how the doctrine of hardship under French law may be used by contractors to renegotiate or terminate their contracts when performance becomes excessively onerous.

Historically the doctrine of hardship was not recognised under French private law. However, the 2016 reform of the French Civil Code introduced a new Article 1995, which formally recognises the doctrine of hardship in French private law.

The two main standard forms of private construction contracts in France both contain price revision clauses,[14] but differ in their approaches to hardship. NF P 03-001 for private building works expressly provides that in the event of a change of circumstances that (1) was unforeseeable when the contract was entered into, (2) which makes performance of the contract excessively onerous for a party, and (3) where the risk of such onerous performance was not assumed by that party, such party is entitled to request the renegotiation of the contract. If the other party refuses to renegotiate or renegotiations fail, the parties shall have recourse to mediation or conciliation before proceeding with litigation or arbitration (Article 9.1.4). NF P 03-002 for civil engineering works, however, does not contain a hardship clause; the default private law position (ie, Article 1195 of the French Civil Code) described above therefore applies.

French administrative law has recognised the doctrine of hardship since the 1916 case Gaz de Bordeaux (French Council of State, the highest administrative court). However, this doctrine differs from that of French private law. It provides that when unforeseeable circumstances for which the contractor is not responsible arise and upset the economy of the contract – without rendering its performance impossible – and cause substantial loss to the contractor, then the contractor remains strictly bound to perform the contract but is entitled to compensation from the public entity.

The purpose of this indemnity is to assist the contractor in overcoming an exceptional and temporary financial difficulty so as to allow the performance of the contract without (or with minimal) interruption. This reflects the legal philosophy behind French administrative law – described above – which prioritises continuity of public services

For the hardship doctrine to apply under French administrative law, the economy of the contract must be upset. The assessment of whether the economy of a contract has been upset is determined on a case-by-case basis as there is no established threshold. For instance, in one case, an increase of 7 per cent of extracontractual costs was sufficient to establish that the economy of the contract was upset.[15] Whereas, in another case, an increase of 10 per cent in the contract price was not considered sufficient for the hardship doctrine to apply.[16]

While the contractor must generally bear part of the extra costs, typically 80 per cent to 90 per cent of the loss is likely to be borne by the public entity.[17]

The hardship doctrine is mandatory law under French administrative law. As a result, it cannot be excluded by contract. If the contract contains a price adjustment formula that only provides minimal protection against economic hardship, the contractor may still be entitled to relief under the administrative doctrine of hardship, provided that the contract economy remains upset after application of the price adjustment formula.[18]

The standard form of contract for public works in France (Cahier des Clauses Administratives Générales – CCAG. – Marchés publics de travaux, last published in 2021) does not contain a price revision clause.

However, it expressly states that such a price revision clause may be agreed between the parties.[19] In addition, the CCAG. – Marchés publics de travaux has essentially codified the French administrative doctrine of hardship. Article 54 provides that when unforeseeable circumstances arise, that a diligent contractor could not have foreseen, and which upset the economy of the contract, the parties shall examine, in particular, the financial impact of this change, in good faith, and determine the compensation to be provided to the contractor. Importantly, Article 54 expressly provides that the price revision is excluded for the assessment of whether the contract economy has been upset.

Supply chain disruptions/delays

In addition to price volatility affecting material purchases, recent projects have experienced abnormal delays and disruptions to delivery dates of essential materials and equipment. Some of these disruptions were tied to lockdowns during the Covid-19 epidemic. Others have been tied to labour disputes affecting international shipping. Some have also been tied to the Ukraine war or to dramatic increases in market demand. Some have also been tied to shifts in sources of manufacturing, eg, as the US and other countries seek to reduce dependence on key products from economies controlled by what are perceived as hostile governments.

People around the world have recently grown accustomed to hearing that ‘supply chain disruptions’ are causing long and unpredictable delays in delivery of consumer products. Construction contractors have similarly been affected by long and often unpredictable delays in obtaining specified materials or equipment that are essential to their work.

In the past, unexpected delays in obtaining key materials have often been treated as a contractor risk. As recent market conditions have brought this issue to the forefront, however, there are increasing pressures to share or reallocate this risk.

Again, practical solutions are likely to include at least treating unexpected supply chain delays as an excusable basis for project time extensions. Other practical solutions may include:

• direct employer pre-purchases of long lead materials and equipment with uncertain delivery dates;

• a shared contingency fund that can be used to cover increased costs associated with unexpected supply chain delays; and

• treatment of unexpected supply chain delays as a basis for equitable compensation.

Regardless of which solutions are adopted, contractors and engineers should contribute their expertise to help employers identify key project components likely to be affected by supply chain delays and to assist in reasonable efforts to mitigate such delays.

FIDIC contracts

The 1999 and 2017 editions of the Red and Yellow Books contain time relief for shortages caused by epidemics or government actions. The 1999 and 2017 editions of the Silver Book, however, do not contain such relief, as these forms place greater risk on the contractor.

Sub-Clause 8.4 [Extension of Time for Completion] of the 1999 edition of the FIDIC Red and Yellow Books provides that:

‘The Contractor shall be entitled subject to Sub-Clause 20.1 [Contractor’s Claims] to an extension of the Time for Completion if and to the extent that completion for the purposes of Sub-Clause 10.1 [Taking Over of the Works and Sections] is or will be delayed by any of the following causes:

(a) a Variation (unless an adjustment to the Time for Completion has been agreed under Sub-Clause 13.3 [Variation Procedure]) or other substantial change in the quantity of an item of work included in the Contract,

(b) a cause of delay giving an entitlement to extension of time under a Sub- Clause of these Conditions,

(c) exceptionally adverse climatic conditions,

(d) Unforeseeable shortages in the availability of personnel or Goods caused by epidemic or governmental actions, or

(e) any delay, impediment or prevention caused by or attributable to the Employer, the Employer’s Personnel, or the Employer’s other contractors on the Site. […].’ (emphasis added).

Sub-Clause 8.5 [Extension of Time for Completion] of the 2017 edition of the FIDIC Red and Yellow Books provides that:

‘The Contractor shall be entitled subject to Sub-Clause 20.2 [Claims For Payment and/or EOT] to Extension of Time if and to the extent that completion for the purposes of Sub-Clause 10.1 [Taking Over the Works and Sections] is or will be delayed by any of the following causes:

(a) a Variation (except that there shall be no requirement to comply with Sub-Clause 20.2 [Claims For Payment and/or EOT]);

(b) a cause of delay giving an entitlement to EOT under a Sub-Clause of these Conditions;

(c) exceptionally adverse climatic conditions, which for the purpose of these Conditions shall mean adverse climatic conditions at the Site which are unforeseeable having regard to climatic data made available by the Employer under Sub-Clause 2.5 [Site Data and Items of Reference] and/or climatic data published in the Country for the geographical location of the Site;

(d) Unforeseeable shortages in the availability of personnel or Goods (or Employer-Supplied Materials, if any) caused by epidemic or governmental actions; or

(e) any delay, impediment or prevention caused by or attributable to the Employer, the Employer’s Personnel, or the Employer’s other contractors on the Site. […].’ (emphasis added).’

As discussed above, a contractor may also be entitled to time relief under the force majeure provisions (in the 1999 edition of the rainbow suite) or Exceptional Events provisions (in the 2017 edition of the rainbow suite), provided that the conditions for such provisions are met.

Italy

In Italy, the previously discussed remedies available in case of supervening circumstances (impossibility and hardship) can also apply to supply chain disruptions/delays. In the past, such disruptions/delays were commonly treated as risks of the contractor. Following the pandemic and outbreak of the Ukraine war, however, employers and contractors have increasingly adopted a more collaborative approach to mitigate the project risks arising from supply chain disruptions and delays. In the author’s view, this is one of the (few) positive consequences of the recent problematic years.

Germany

In Germany the principles set out in the first chapter related to war as a force majeure event can be applied to supply chain disruption and delays as well. In addition, a supplier/contractor may use such events as a defence against claims for damages since those necessitate fault of the supplier/contractor who might be excused.

Austria

In this case as well, problems in the supply chain are generally treated as a responsibility in the sphere of the contractor. The contractor normally has the ability to choose its suppliers. Even with a nominated subcontractor, the contractor usually remains responsible for problems in the supply chain.[20]

In Finland, as in some other EU jurisdictions, (…) force majeure or hardship events may also be applied in case of disruptions in the supply chain, to the extent proven by the contractor claiming time and cost.

ÖNORM B 2110 does not provide for any deviating regulation in this regard. The considerations described in the first chapter thus also apply here.

Finland

In Finland, as in some other EU jurisdictions, the previously discussed force majeure or hardship events may also be applied in case of disruptions in the supply chain, to the extent proven by the contractor claiming time and cost. The discussed YSE 1998 general conditions are also widely applied in construction subcontracting.

As discussed in connection with Italy, and notwithstanding the general notion that supply chain disruptions are typically a contractor risk, Finland saw with Covid-19 and now with effects of the Ukraine crisis that employers are more willing to accept a collaborative risk share approach. Most typically, unforeseen supply chain disruptions and delays are handled as variations, or the employers are accepting compensation for alternative purchases or acceleration costs where the originally intended procurement’s availability or schedule has been affected.

England

England has undergone two recent events which have led to supply chain disruption, Brexit and Covid-19. Covid-19 has generally been considered as the equivalent of a force majeure event or as a risk of the contractor, where the contractor had sufficient notice of Brexit to take it into account.

In the NEC4 form, supply chain disruption and events such as Covid-19 would fall within Core Clause 19, as referred to above.

The costs of supply chain disruption may fall within the fluctuation provisions of the JCT form. See above on fluctuations.

From an English common law position, the doctrine of frustration may work as a defence to a claim for loss sustained by the employer as a result of supply chain delays to the works.

France

French private law does not contain any specific provision entitling a contractor to additional time due to delays and disruptions to delivery dates of essential materials and equipment.

However, a contractor may be entitled to time relief under the force majeure provision of Article 1218 of the French Civil Code, provided it can establish that the event was unforeseeable at the time of the entry into the contract and prevented it from performing its obligation. In this respect, it should be noted that Article 1218 only provides that the event shall prevent the debtor from performing ‘its obligation’, meaning any of the debtor’s obligations but not all of its obligations. In the context of a construction contract, a contractor typically has an obligation to complete the works by a certain date. If delays in the delivery of essential materials and equipment prevent the contractor from completing the project on time, it may be entitled to time relief pursuant to Article 1218.

A contractor may also be entitled to request the renegotiation of the contract or, if the other party refuses to renegotiate or renegotiations fail, request the court to revise or terminate the contract pursuant to Article 1995 of the French Civil Code, provided the conditions of hardship under French private law (described above) are met.

The main standard forms of contract for private works do not provide time relief for delays and disruptions to delivery dates of essential materials and equipment. However, they do provide that a contractor may be entitled to time relief due to force majeure events.[21] They also allow for the application of the hardship provision of Article 1195 of the French Civil Code, as described above.

French administrative law does not contain any specific provision granting time relief due to delays and disruptions to delivery dates of essential materials and equipment. However, time relief may be available under the doctrine of force majeure as applied by French administrative courts. Compensation may also be available under the hardship doctrine.

Indeed, as mentioned above, the standard form of contract for public works in France (CCAG. – Marchés publics de travaux) has essentially codified the French administrative doctrine of hardship.

Exchange rate fluctuations

Unlike some of the other circumstances discussed above, there is nothing especially new about the risk of international current exchange rate fluctuations in construction contracting. Projects with participants from multiple countries are generally accustomed to fixing contract payments in a stable currency, and there are existing financial vehicles by which contractors can hedge against currency fluctuations during the life of an extended job.

As the global marketplace changes at a rapid rate, however, many contractors and suppliers may find themselves entering international transactions for the first time. Although some countries have long experience with endemic inflation (affecting the exchange rate value of their currency), many others have no such experience. Those who are new to international market volatility may need to be reminded about the need to protect their pricing. This applies both to the revenues they receive and to the prices they pay to their own subcontractors and suppliers.

Some contractors will feel adequately protected if their revenue is fixed in their home currency. Others may purchase a hedge guarantee against exchange rate fluctuations. Others may be able to negotiate a contract term promising equitable compensation for unexpected currency fluctuations during the life of their project.

FIDIC contracts

The 1999 and 2017 editions of the Red, Yellow and Silver Books do not provide protection for contractors against exchange rate fluctuations. Sub-Clause 14.15(e) of the 1999 edition and Sub-Clause 14.15(f) of the 2017 edition of the rainbow suite merely provide that ‘if no rates of exchange are stated in the [Appendix to Tender/Contract Data], they shall be those prevailing on the Base Date and published by the central bank of the Country’.

United States

Example: US Code of Federal Regulations s 200.440 [Exchange Rates]

(a) Cost increases for fluctuations in exchange rates are allowable costs subject to the availability of funding. Prior approval of exchange rate fluctuations is required only when the change results in the need for additional Federal funding, or the increased costs result in the need to significantly reduce the scope of the project. The Federal awarding agency must however ensure that adequate funds are available to cover currency fluctuations in order to avoid a violation of the Anti-Deficiency Act.

(b) The non-Federal entity is required to make reviews of local currency gains to determine the need for additional federal funding before the expiration date of the Federal award. Subsequent adjustments for currency increases may be allowable only when the non-Federal entity provides the Federal awarding agency with adequate source documentation from a commonly used source in effect at the time the expense was made, and to the extent that sufficient Federal funds are available.

Italy

Italian case law generally considers currency exchange rate fluctuations to be a contractor risk, unless these fluctuations are extraordinary and unforeseeable.[22]

In light of the above, Italian contractors typically prefer to use their own currency and to fix a date of reference to be used in calculating damages. In any case, where it is not possible to fix a price in Euros, the risk of currency fluctuation is typically handled through purchasing a hedge guarantee.

Germany

The situation in Germany is comparable to the Italian position.

Finland

In Finland, currency exchange rate fluctuations are considered contractor risks, unless the effects are so considerable and unforeseeable that the application of section 36 of the Finnish Contracts Act (as explained above) could be invoked.

Austria

Since the introduction of the Euro, as electronic currency in 1999 and as physical currency in 2002, foreign exchange risk has diminished significantly. Indirectly, however, this risk continues to have an impact when purchasing goods traded in dollars (especially crude oil).

Some kind of reasonable balance in risk allocation is an important part of anticipating the things that cannot clearly be anticipated.

In Austria, foreign exchange risk is primarily borne by the contractor, as it decides where and under what conditions to purchase materials and equipment. Since the foreign exchange risk can easily be hedged through forward contracts, this risk remains with the contractor, even in circumstances of extraordinary fluctuations.

ÖNORM B 2110 does not contain any special regulations in this respect; adjustments in line with price adjustments provisions may possibly lead to corresponding price modifications indirectly.

England

In England contracts tend not to refer to currency exchange rate fluctuations. The NEC form does anticipate issues with exchange rate fluctuations by having an Option X3 for multiple currencies (for use with NEC 4 Options A and B).

The JCT forms do not expressly deal with currency fluctuations, but that contingency would potentially come under one of the Fluctuation Options explained above.

France

French private law does not contain any specific provision entitling a contractor to compensation for exchange rate fluctuations.

However, a contractor may request the renegotiation of the contract or, if the other party refuses to renegotiate or renegotiations fail, request that a court revise or terminate the contract if the conditions of hardship under French private law are met, pursuant to Article 1995 of the French Civil Code.

The main standard forms of contract for private works do not include any specific provision entitling a contractor to compensation for exchange rate fluctuations. However, they allow for the application of the hardship provision under Article 1195 of the French Civil Code, as described above.

French administrative law does not provide any specific financial relief for exchange rate fluctuations. However, financial compensation may be available under the hardship doctrine, provided that the economy of the contract is upset.[23]

Furthermore, as mentioned above, the standard form of contract for public works in France (CCAG. – Marchés publics de travaux) has essentially codified the French administrative doctrine of hardship.

Conclusion

The construction industry inevitably imposes risks on all its participants. Those who provide goods or services reasonably expect to earn a profit commensurate with the risks that they have agreed to accept. Risks are often assigned to a particular party, but they can also be shared through contingency allowances, liability caps, or through project delivery systems that are designed to share risks of unexpected conditions.

Although it may be reasonable to expect some degree of the unexpected, there are practical limits on the financial risks that a for-profit contractor or supplier can afford to bear. Either through insurance or assumption of risk by public employers, many risks of unexpected conditions end up ultimately being borne by the taxpaying public. Even on private projects where unexpected risks are borne by the employer, they are often ultimately transferred to the general public that purchases goods and services from the employer. Some kind of reasonable balance in risk allocation is an important part of anticipating the things that cannot clearly be anticipated.

[1] Italian Civil Code (as of 2025), Art 1256, first para.

[2] Court of Genoa, decision 11 July 1996.

[3] Italian Civil Code (as of 2025), Art 1660.

[4] BGH – VII ZR 106/07 – 8 May 2008. See http://juris.bundesgerichtshof.de/cgi-bin/rechtsprechung/document.py?Gericht=bgh&Art=en&nr=44069&pos=0&anz=1.

[5] BGH – XII ZR 8/21 – 12 January 2022; OLG Düsseldorf - 10 U 192/21 – 23 June 2022.

[6] Riedler in Schwimann/Kodek, ABGB Praxiskommentar, marginal no 9 to s 901.

[7] Italian Civil Code (as of 2025), Art 1664, first para.

[8] Francesco Goisis and Pasquale Pantalone, ‘La revisione dei prezzi negli appalti pubblici come condizione per l'attuazione del PNRR, tra principi euro unitari e vischiosità normative nazionaliʼ (March 2023) Diritto Amministrativo, 1, 97.

[9] Italian Public Contracts Code, Art 60.

[10] Samples in the German language could read as follows:

Für Angebote: „Aufgrund der pandemiebedingten sehr dynamischen Preisentwicklung für……. (Vorprodukte) erhalten wir von unseren Lieferanten derzeit nur Tages- bzw. Wochenpreise. Wir bitten Sie daher um Verständnis, dass wir angesichts der sich daraus ergebenden Dynamik – unser Angebot nur unverbindlich / freibleibend abgeben und uns an die in unserem Angebot genannten Preise nur bis zum …. gebunden halten können.’

Oder: „Die Preise des obigen Angebots sind Festpreise bei einer Lieferung bis zum ……. Danach gilt: Sollte sich der Einkaufspreis/Marktpreis für benötigte Materialien des obigen Angebots zum Zeitpunkt der Lieferung gegenüber dem Zeitpunkt der Angebotserstellung um mehr als …… Prozent nachweislich erhöht haben, ändert sich der Einheitspreis entsprechend der Gewichtung des Materialanteils in dieser Position.’

Als Klausel in einem Vertrag: „Für den Fall, dass nach Vertragsschluss die von ………. zu zahlenden Netto-Einkaufspreise für Vormaterialien/Rohstoffe (insbesondere …..) zum Zeitpunkt der Lieferung um mehr als ……Prozent steigen sollten, hat das Recht, den Eintritt in ergänzende Verhandlungen zu verlangen, mit dem Ziel, durch Vereinbarung eine angemessene Anpassung der vertraglich vereinbarten Preise für die betroffenen vertragsgegenständlichen Materialien herbeizuführen.

[11] See www.jctltd.co.uk/docs/Fluctuations_Options_BC/DB-2016-FluctuationsOptionsBC.pdf, accessed 25 July 2025.

[12] See for instance, Bordeaux Court of Appeal, 27 April 2021, no 20/04054.

[13] TC Paris, 14 December 2022, no 2022033136.

[14] Articles 9.4.1.1 and 9.4.1.2 of NF P 03-001 and NF P 03-002.

[15] Société Altagna, CAA Marseille, 17 January 2008, no 05MA00493.

[16] Société Balas Mahey, CAA Paris, 10 July 2015, no 12PA04253.

[17] André de Laubadère and others, Traité des Contrats Administratifs (2nd edn, LGDJ, 1984), vol II, 623 (para 1394).

[18] Philippe Malinvaud, Droit de la Construction, (7th edn, Dalloz Action, 2018), 1343 (para. 417.447).

[19] Article 9.4, CCAG. – Marchés publics de travaux.

[21] NF P 03-0001, Article 10.3.1.2; NF P 03-0002, Article 10.5.1.2.

[22] See Italian Supreme Court decisions 11200/2003 and 1027/1995.

[23] Philippe Malinvaud, Droit de la Construction (7th edn Dalloz Action, 2018) 1343 (para 417.446).

Thomas Frad is a Partner at KWR (Karasek Wietrzyk Rechtsanwälte) in Vienna, Austria and can be contacted at thomas.frad@kwr.at.

Douglas Stuart Oles is a Senior Partner at Smith Currie Oles in Seattle, Washington, USA, and can be contacted at dsoles@smithcurrie.com.

Richard Bailey is a Partner at Druces in London, UK, and can be contacted at r.bailey@druces.com.

Yann Schneller is an Avocat and the Founding Partner of DARCI (Dispute Avoidance and Resolution for the Construction Industry) in Paris, France, and can be contacted at yann.schneller@darcilaw.com.

Claus H Lenz, Rechtsanwalt, is an Attorney-at-Law at Lenz Dispute Resolution in Hamburg, Germany, and can be contacted at lenz@lenz-disputeresolution.com.

Emma Niemistö is an Attorney-at-law and Partner at Borenius Attorneys in Helsinki, Finland, and can be contacted at emma.niemisto@borenius.com.

Arianna Perotti is an Avvocato and Of Counsel at Dardani Studio Legale in Milan, Italy, and can be contacted at arianna.perotti@dardani.it. |