Doing business in a ‘sunburnt’ country – international contractors on Australian projects

Credit: Shutterstock

Sean Kelly

Clayton Utz, Melbourne

Allison van Beers

Clayton Utz, Melbourne

|

Positive change is being enacted to facilitate international participation in Australian infrastructure projects. This paper highlights various factors that are prominent in, and sometimes unique to, Australian projects that international contractors entering the Australian market should pay close consideration to, including: the intersection between statutory limitation periods and projects with long concession periods; opportunities from, and risks of, partnering with local companies in joint venture arrangements; delivery phase procurement (labour and materials) policies, statutory liability for international supply chains and regulated payment processes; and regulatory complexity derived from differing policies across state and territory borders and the federal jurisdiction.

|

Introduction

With a steady pipeline of large projects, particularly in the resources and transport industries, Australia has seen overseas companies with expertise in those fields venture into the construction market. The presence of international participants is considered to be positive by governments stocking the pipeline. In June 2019 the Premier of the state of Victoria, Daniel Andrews, said:‘It doesn’t matter what part of the world they’re from, whether they are from Europe or from China, we need more and more construction capacity to go along with the investments that we’re making.’1

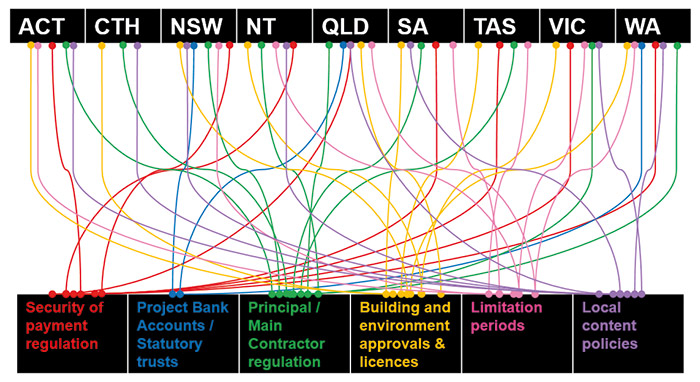

This paper discusses a number of key issues that international contractors should be aware of across all phases of the project lifecycle from tender phase to delivery phase, as well as powerful remedies available in certain types of project-related disputes. Common themes emerge in the paper. Most prominent is the impact of Australia’s nine jurisdictions, each with wide-spanning and subtly different regulatory regimes, the complexity of which is demonstrated in the below graphic:

Figure 1: Sample of regulatory regimes across Australia’s nine jurisdictions

This makes partnering with a local firm an attractive enterprise structure for overseas participants: local knowledge and experience can be priceless. However, partnering with local firms is not a panacea.

Tender phase: bid cost reimbursement and risk allocation during concession periods

Tenders create a competitive tension that is viewed by many as an essential precondition to achieving the best price that the market can offer. The sophistication of tenders can result in significant sunk costs for losing tenderers.

However, there is the prospect of recouping some tender costs. Bid cost reimbursement regimes are increasingly prevalent in Australia. These regimes increase the range of companies willing to bid for complex infrastructure projects, which in turn drives better solutions and competitive pricing for the project as a whole.

Competitive pricing will also take into account the effects of the local statutory environments. For example:

• contractual defects liability periods (DLPs) intersecting with statutory limitation periods; and

• extended statutory limitation periods unique to the construction industry.

Standard contractual DLPs often run for 12 or 24 months from the contractual date of services completion. However, state and territory legislation create longer periods during which claims for breach of contract, breach of deed or in tort may be pursued by the claimant.

International delivery partners should also be aware of specific limitation periods that apply to ‘building actions’ that can extend or cap statutory limitation periods on infrastructure projects. For example, section 134 of the Building Act 1993 (Vic) states that:

‘despite anything to the contrary in the Limitation of Actions Act 1958 or any other Act or Law, a building action cannot be brought more than 10 years after the date of the occupancy permit in respect of the building work… or [the date of issue] of the certificate of final inspection’.

This provision sets the limitation period for a ‘building action’ at ten years, meaning that in Victoria, a six-year limitation period for breach of contract may be extended, while the 15-year limitation period for breach of deed may be limited. It also means that a claim in tort for late manifesting damage, delaying when the cause of action accrued, may also be capped.2

Similar building-specific limitation periods apply in jurisdictions across Australia; however, the effects vary. For example, the Australian Capital Territory legislature has expressly enacted a building industry-specific limitation period in section 142(3) of the Building Act 2004 (ACT) with wording designed to preserve other shorter statutory limitation periods.

Related risk allocation devices involve repeating contractual warranties. Statutory limitation periods commence running from the date that the relevant cause of action accrued. Many infrastructure project agreements incorporate ‘repeating representations and warranties’ clauses, which can have the effect of creating a new breach, and therefore a new accrued cause of action, throughout the term of the project.

For an international participant, the most crucial decision for structuring their role... is whether or not to partner with a local construction company

|

Commonly used drafting is as follows:

‘Unless otherwise expressly stated in this agreement, each representation and warranty given by the delivery partner under this agreement:

(a) is made on the date of this agreement; and

(b) is repeated each day during the period from the date of this agreement to the expiry date.’

Such clauses may be necessary where commercial imperatives require that the delivery contractor ‘stand behind’ the build quality and design life of the works during a long-term concession period, following which the asset is ‘returned’ to the relevant state or territory. This is frequently necessary for public–private partnership or private finance initiative projects, which usually grant a private-sector operator the right to operate the asset during a concession period that exceeds the standard limitation periods. A first-principles analysis is required on a case-by-case basis to determine whether such clauses contract out of the statutory limitation period(s) that may apply to the project.

Enterprise structures: joint ventures

For an international participant, the most crucial decision for structuring their role in the delivery of an Australian project is whether or not to partner with a local construction company.

Joint ventures are appropriate where multiple forms of expertise or input are required, including technical expertise, networks and funding.

On one hand, the scope of success can be very wide, allowing the international participant to rely on the local company’s experience and knowledge. However, the scope of loss from a failed joint venture is also potentially very wide: joint and several liability may bite where a local participant becomes insolvent and the relationship may sour where fiduciary duties contest with each party’s commercial goals.

The key advantage of entering a joint venture agreement with a local organisation is relying on the local organisation’s experience and knowledge of the jurisdiction and applicable regulations. Approvals and licences required to be obtained or held by a company intending to perform construction work in most Australian jurisdictions include:

• planning and building permits;

• building licences;

• ‘Principal Contractor’ responsibilities under workplace health and safety legislation; and

• goods and services tax registration.

In addition, where project agreements require contractors to demonstrate utilisation of local labour and/or supplies,3 local participants are likely to be better placed to navigate these requirements.

Regulating the relationship: dealing with fiduciary duties

There is usually some overlap between the duties of a fiduciary and the mutual obligations of joint venture parties. This is because the central aspects of a commercial joint venture often include that the parties work together, and each party exercises discretion for mutual gain. Indeed, fiduciary duties have been found to exist within a joint venture relationship,4 even though a joint venture does not automatically create a fiduciary relationship in Australia.5

Fiduciary duties involve the imposition of additional obligations on parties, which can hamper a party’s ability to pursue commercial gains. Whether or not a joint venture relationship is fiduciary in nature will often depend on the terms of the agreement, including whether such terms put one party in a position to exercise discretion for the benefit, or at the expense, of the other. It is also possible for a fiduciary relationship to arise before a final joint venture agreement is executed by the parties,6 based upon the particular factual circumstances of the relationship and the joint venture project.

Although the precise content of fiduciary duties will vary based on the nature of the relevant relationship, in a joint venture such duties generally involve the fiduciary:

• acting in the best interests of the other party or jointly for all parties and the joint venture as a whole;

• not separately profiting from the relationship (other than fees as agreed and/or indemnification for losses) and accounting for profits;

• avoiding conflicts of interest;

• avoiding obtaining an advantage at the expense of, or causing disadvantage to, another joint venturer in relation to the joint venture project; and

• accounting for an improper advantage if obtained, irrespective of whether the improper advantage was actively hidden from the other joint venturer or could have been discovered by it.

Joint ventures are not standalone legal concepts in Australian law and, because of the lack of general propositions that apply to joint venture arrangements,7 the legal and equitable obligations arising from an arrangement that binds joint ventures can be difficult to predict.8 This unpredictability can be reduced if the joint venturers are willing to address their mutual responsibilities in a carefully prepared joint venture agreement.

Parties to a joint venture may wish to exclude the role of fiduciary duties from their joint venture relationship. Where commercial certainty is a paramount consideration, it is usually advisable that the parties codify their respective rights and responsibilities in a comprehensive joint venture agreement. There are generally two options for codifying all of the joint venture rights and responsibilities in a joint venture agreement:

• expressly excluding fiduciary relationships and duties; and

• creating contractual obligations that are inconsistent with the imposition of fiduciary duties.

Retaining for joint venturers the freedom to act to their own advantage in their own discretion may preclude the existence of supplementary fiduciary duties.9 However, where this freedom of discretion can be isolated to specific activities, fiduciary duties may continue to exist in respect of other activities contemplated by a joint venture agreement.10

Project delivery

Having successfully tendered for a major infrastructure project and implemented a suitable enterprise structure, an international contractor will encounter a number of issues unique to Australian projects during the delivery phase.

In a vacuum, there are no limits to the ways in which a project can be resourced. Any approach to resourcing is likely to encounter challenges. Despite national employment legislation, workplace health and safety laws vary by jurisdiction, with some jurisdictions requiring head contractors to perform Principal Contractor roles as that term is defined in the legislation.11

Finding a balance between utilising an international participant’s knowledge and utilising the local workforce can be advantageous to overseas participants

|

In the state of New South Wales (NSW), Principal Contractors bear certain responsibilities in relation to managing work sites and construction work, including the creation and maintenance of various work site management plans. This generates a significant administrative burden for organisations not frequently performing the Principal Contractor role in the relevant jurisdiction and places the organisation at risk in relation to breach of the Principal Contractor responsibilities (the penalties for which are significant, including fines and, in certain instances, imprisonment).

Finding a balance between utilising an international participant’s knowledge and utilising the local workforce can be advantageous to overseas participants. Although varying by jurisdiction, government policies encourage (and can incentivise) utilisation of the local workforce. For example:

• In Victoria, the Social Procurement Framework12 and the Local Jobs First Policy, including the Major Project Skills Guarantee (MPSG),13 require certain government agencies and bodies to have in place social procurement plans and strategies applicable to tendering and project delivery. The MPSG is a workforce development policy designed to ensure job opportunities for apprentices, trainees and cadets on infrastructure projects.

• In the federal jurisdiction, the Commonwealth Indigenous Procurement Policy14 aims to stimulate indigenous entrepreneurship and business development by requiring certain commonwealth entities in respect of certain building contracts to meet mandatory indigenous employment (workforce) and supplier use (supply chain) minimum requirements.

Many large Australian infrastructure projects include ‘local content’ obligations requiring the use of certain proportions of materials and resources sourced from the local jurisdiction. In Victoria, the Victorian Industry Participation Policy (VIPP)15 is applied when assessing tenders for infrastructure projects. Australia and New Zealand are considered to be a single ‘local content’ market for this purpose.16

The process for applying the Local Jobs First Policy in Victoria, including both the MPSG and VIPP, is set out in section 3.2 of the Local Jobs First Agency Guidelines. Step 3 requires the relevant agency to specify the requirements in tender documents. Step 4 requires tenderers to obtain an acknowledgement letter from an independent body, the Industry Capability Network – Victoria (ICN), indicating compliance with local content requirements. A failure to obtain a letter from the ICN means that the tender is not complete, and ‘this would mean the end of the procurement process for the bidder’.17

This approach to promoting local industry is not uniform. For example, the NSW Procurement Board has recently issued the Procurement (Enforceable Procurement Provisions) Direction 2019. Effective from 29 November 2019, the Direction, among other things, precludes a NSW agency from imposing conditions to use domestic content or suppliers, or similar conditions to encourage local development in Australia.

The Murray Report recently recommended making security of payment laws nationally consistent

|

Irrespective of which state or territory policies apply, international contractors can still rely upon international supply chains, but they should be aware of state and territory legislation that can have the effect of imposing manufacturer’s warranties on the importer of goods. Under the Goods Act 1958 (Vic), a supplier of goods owes implied duties regarding fitness for purpose and merchantable quality of the goods ‘whether he be the manufacturer or not’. This can be beneficial to upstream parties and detrimental to the importer, who may have no control over manufacturing standards in the source jurisdiction.

Finally, progress payment statutory regulation is now relatively common across the world, especially in commonwealth jurisdictions. However, certain aspects of the security of payment legislation across the Australian jurisdictions can trip up savvy international contractors. Key issues include:

• the wide application of security of payment legislation (in respect of both project and claim size);

• rigid and complex regimes (such as the Victorian legislation’s approach to payment claims concerning ‘claimable variations’ and ‘excluded amounts’); and

• the multitude of procedural differences between each jurisdiction’s legislation.

These critiques might be shared equally by Australian participants. Indeed, the Murray Report18 recently recommended making security of payment laws nationally consistent. At present, little movement has been made towards this goal.

In a similar vein, the requirement for project bank accounts or statutory trusts in some (but not all) Australian jurisdictions is an example of further regulation of the payment process. In the state of Queensland, three bank accounts are required: a general trust account, a retention trust account and a disputed funds trust account.19 This can create an additional administrative burden for international participants.

Close-out and recovering losses

This paper will not canvass the various causes of action and associated remedies that may be available on Australian infrastructure projects. However, international participants should be aware of particular remedies that may not be common in their home jurisdiction, but which can be particularly powerful in Australia.

The Consumer Law imposes statutory standards that provide civil entitlements to recover losses caused by conduct that is misleading or deceptive, or which may mislead or deceive, or by unconscionable conduct.

These statutory rights apply alongside contractual rights. While it may remain possible to impose monetary limits on liability via contractual provisions,20 it is not possible to exclude altogether the operation of the standards, which have been recognised as serving public policy. Accordingly, contractual time bar provisions may be effective to prevent a party from bringing late claims under a contract; however, that party may still be able to bring claims under the Consumer Law irrespective of failure to comply with contractual notice provisions.21

Some overseas jurisdictions have been more willing than Australia to imply obligations of good faith into all commercial contracts as a matter of law; however, that is not the law of Australia.22 This is partly offset by the relatively broad statutory obligations to avoid misleading or deceptive conduct. Subjective intent to mislead or deceive is not required to be in breach of these statutory standards. This can come as a surprise to some overseas participants and it can provide remedies that they might not have thought they had access to.

Conclusion: recurring themes

To take full advantage of the recent boom in infrastructure projects across Australia, international contractors must be aware of and fully understand the large number of policies and regulations that apply to Australian projects, which often differ across the various state, territory and federal jurisdictions.

Notwithstanding the regulatory maze, there remains great opportunity for international contractors. The need to diversify expertise on Australian construction projects has been recognised and policies are being implemented to achieve this outcome.

Notes

1 Clay Lucas and Timna Jacks, ‘Losers paid out in transport bids’, The Age, accessed 14 June 2019.

2 Brirek Industries Pty Ltd v McKenzie Group Consulting (Vic) Pty Ltd[2014] VSCA 165.

3 See Local Jobs First – Victorian Industry Participation Policy.

4 Blong Ume Nominees Pty Ltd v Semweb Nominees Pty Ltd (2017) 123 ACSR 19.

5 United Dominions Corporations Ltd v Brian Pty Ltd (1987) 157 CLR 1, 10.

6 See arguments raised in Noble Earth Technologies Pty Ltd v Hampic Pty Ltd (in liq) (t/as Cyndan Chemicals) [2017] NSWSC 502 and Management Service Australia v PM Works [2017] NSWSC 1743.

7 See n 5 above.

8 For example, compare Blong Ume Nominees Pty Ltd v Semweb Nominees Pty Ltd (2017) 123 ACSR 19 with Red Hill Iron Ltd v API Management Pty Ltd [2012] WASC 323.

9 Ibid, Red Hill Iron.

10 Ibid.

11 See, eg, harmonised legislation: Work Health and Safety Act 2011 (ACT), Work Health and Safety Act 2011 (NSW), Work Health and Safety (National Uniform Legislation) Act 2011 (NT), Work Health and Safety Act 2011 (Qld), Work Health and Safety Act 2012 (SA) and Work Health and Safety Act 2012 (Tas).

12 State Government of Victoria, Victoria’s social procurement framework, April 2018, www.content.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2018-08/Victorias-Social-Procurement-Framework.PDF

13 Provided for by the Local Jobs First Act 2003.

14 Australian government, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, Indigenous Procurement Policy overview, 26 November 2018, www.pmc.gov.au/resource-centre/indigenous-affairs/indigenous-procurement-policy-overview

15 Which is also part of the Local Jobs First Policy of the Victorian government.

16 Local Jobs First Policy (October 2018), p 4, s 5.1.

17 Local Jobs First Agency Guidelines (October 2018), pp 3–4, s 3.2.

18 John Murray AM, Review of Security of Payment Laws (December 2017), https://docs.employment.gov.au/system/files/doc/other/review_of_security_of_payment_laws_-_final_report_published.pdf

19 See Building Industry Fairness (Security of Payment) Act 2017 (Qld).

20 For consideration of monetary caps on liability, see Owners SP 62930 v Kell & Rigby [2009] NSWSC 1342, Lane Cove Council v Michael Davies & Associates and Others [2012] NSWSC 727 and Firstmac Fiduciary Services Pty Ltd & Anor v HSBC Bank of Australia Limited [2012] NSWSC 1122.

21 See Brighton Australia Pty Ltd v Multiplex Constructions Pty Ltd [2018] VSC 246 where a time bar was found to be inapplicable in respect of a claim made under section 18 of the ACL as it was found to be void for being against public policy. See also Omega Air Inc v CAE Australia Pty Ltd [2015] NSWSC 802.

22 See Aurizon Network Pty Ltd v Glencore Coal Queensland Pty Ltd & Ors [2019] QSC 163 for a detailed discussion of this issue.

Back to top