Climate crisis: lawyers say legal toolbox for holding governments to account is growing

Joanne HarrisFriday 22 September 2023

Over the summer, the Northern Hemisphere faced fire, floods and heatwaves. Yet some governments are pulling back from green policy commitments or facing pressure to do so.

In late September, the UK government scrapped or delayed its green plans, including pushing back a ban on the sale of petrol and diesel cars to 2035, while affirming its commitment to ‘net zero by 2050’. It says it’s ‘reducing costs on British families while still meeting international commitments’. However, Chris Stark, Chief Executive of the UK’s Climate Change Committee, an independent, statutory body, said that ‘the government needs to look again at the policies. We need to do more’ and that the policy changes are not about doing more, but less.

In July meanwhile, UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak announced he would approve over 100 new licences this autumn to drill for oil and gas in the North Sea. The government argues the UK will still need oil and gas to provide 25 per cent of its energy even by 2050.

Environmental protest groups such as Just Stop Oil are placing increasing pressure on governments to take significant action to address the climate crisis. There’s a question however as to whose job it should be to hold governments to account to ensure they meet the pledges they’ve made.

Caroline May, Head of Sustainability, Europe, Middle East and Asia at Norton Rose Fulbright in London, says the landscape of environmental protest and lobbying is changing. ‘When I was a young lawyer, environmental protest groups were seen as radical, but over the course of my career a number of NGOs [non-governmental organisations] are now seen as mainstream and indeed authoritative voices in this space. So today’s activists may be tomorrow’s authoritative voices’, she adds.

Litigation is a path and we’re seeing right now it’s growing in Brazil

Antonio Augusto Rebello Reis

Climate Change Officer, IBA Environment, Health and Safety Law Committee

As the debate has shifted, new players have entered the world of environmental campaigning. In 2008, environmental lawyers’ group ClientEarth launched its first legal action against new coal power plants in the UK. Since then, the organisation has filed hundreds of cases against governments and corporates to challenge claims and policies relating to the environment, recording significant victories.

For example, a complaint filed with the UN in 2008, which argued that the EU was failing to comply with its duties to give the public access to the courts to bring cases under the Aarhus Convention, eventually resulted in a change to the bloc’s legislation, allowing much wider challenges to EU environmental policies. ‘Climate litigation is a powerful lever to trigger system-level change. It isn’t always a silver bullet, but legal cases are important for reminding corporations and governments of their obligations. The impacts of the climate crisis are happening now and getting unignorably worse. As such, people are turning to the courts to seek justice’, says a spokesperson from ClientEarth.

The organisation adds that the legal toolbox is growing, with more climate-linked human rights cases being filed as well as an increasing amount of litigation related to climate-related financial risk. ‘Every positive precedent opens the door to a proliferation of cases fought on similar arguments, with game-changing climate victories recently won in German, Dutch and French courts, and each judgment highlights how governments and corporations that are dragging their feet on climate action can no longer do so without consequences’, adds the spokesperson.

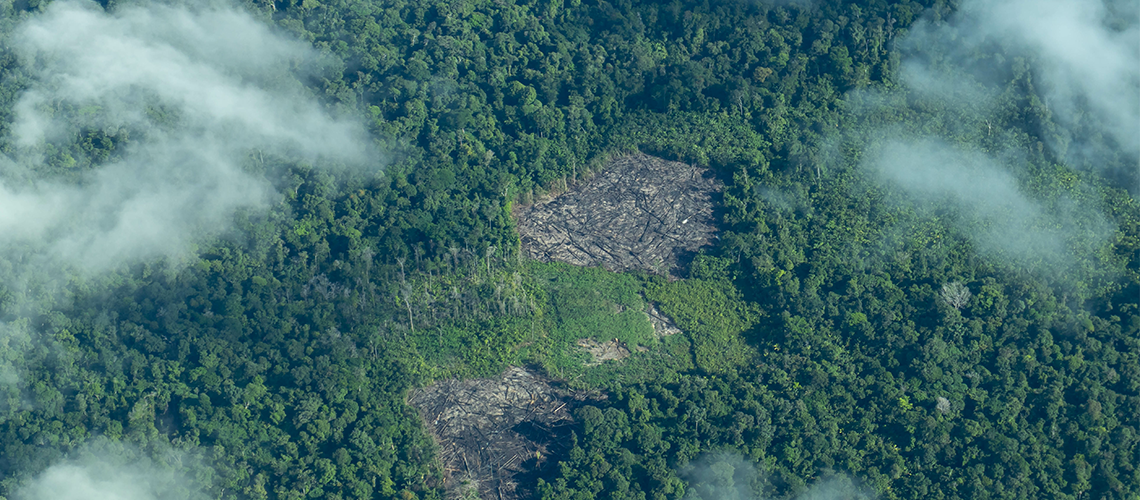

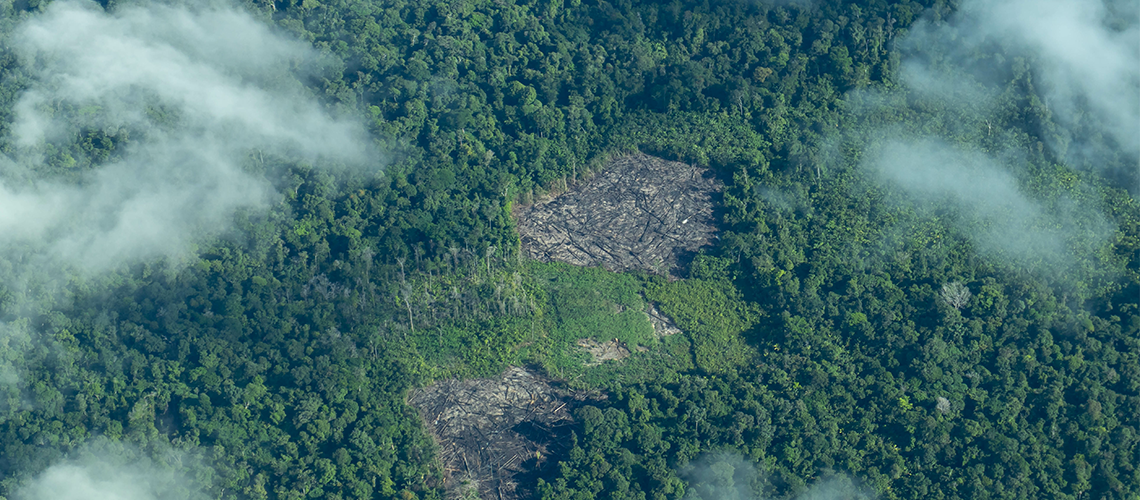

Litigation is also being used elsewhere in a bid to force governments to keep their promises. In Brazil, the largely independent public prosecutor’s office is able to sue the government and has used that power to bring environmental cases. In 2022 the Brazilian Supreme Court found that the government had failed to ensure Brazil’s Amazon Fund – set up to protect the rainforest – was functional and that it must be revived. Crucially, the Court also ruled that environmental law treaties are more important than regular laws in the legal hierarchy.

‘Litigation is a path and we’re seeing right now it’s growing in Brazil’, says Antonio Augusto Rebello Reis, Climate Change Officer on the IBA Environment, Health and Safety Law Committee and a partner at Mattos Filho in Rio de Janeiro. ‘The Supreme Court in Brazil has been demonstrating it will put forward strict decisions on compliance with climate goals.’

But not everyone has the expertise, patience or funding to bring litigation, or the guts to sue a government. That’s why lawyers believe there are other ways to encourage authorities to uphold their climate pledges. Florencia Heredia, Chair of the IBA Energy, Environment, Natural Resources and Infrastructure Law Section and a partner at Allende & Brea in Buenos Aires, says that investors are putting pressure on companies to meet corporate pledges, which in turn forces governments to regulate appropriately.

‘Corporates are already shaping the agenda and are in many cases hugely ahead’, adds May. ‘The big driver for corporates now is a lot of the financial frameworks that are coming out around climate change and energy transition and sustainability, providing access to capital but also requiring environmental improvements and performance.’

Particularly for developing nations, where growing the economy is the government’s priority, ensuring that companies are investing and thriving is a key driver. The climate agenda in places such as Latin America is very different from that of Europe or the US. However, Rebello says corporate pressure can still be applied to make change happen. ‘It may be possible that if the government plays it right Brazil plays a very important role in the next years in decarbonising industries in general’, he says. ‘We need investment to grow towards this, and if national and international investors push for green products in Brazil I don’t see the government having a way around it.’

This is where the legal community can play its part. ‘The role of law is to shape the framework in which all of these policies need to be delivered, and it’s a very important tool,’ May explains. ‘Lawyers are very important advocates for the legal frameworks that have been put in place and for assisting clients with implementation and best practice. As such, environmental and energy lawyers have a vital role to play in delivering the necessary transitions to net zero and sustainable solutions.’

‘We as lawyers have a role which is extremely relevant in the energy transition area because we advise clients, we work with companies and we interact with governments and regulators’, adds Heredia. ‘We need to be the voice of what’s done right.’

Law societies and bar associations globally are taking action to help legal practitioners understand their role moving forward. For example, the Law Society of England and Wales’ Guidance for Solicitors on Climate Change, published in April, assists organisations with managing their business in a manner that’s consistent with the transition to net zero. It also provides guidance for solicitors on how the physical risks of the climate crisis and climate legal risks may be relevant to client advice, and how solicitors’ professional duties interplay with issuing legal advice in the context of the climate crisis.

*Thank you to Lara Douvartzidis, a member of the IBA’s Legal Policy & Research Unit, for her assistance with this article.

Image credit: Tarcisio Schnaider/AdobeStock.com