Venezuela: Latin America’s migration crisis ‘on the scale of Syria’

Ruth Green, IBA Multimedia Journalist

More than 3.3 million people have fled Venezuela since 2015. The United Nations says this figure could rise to 5 million by the end of 2019 as ongoing economic and political turmoil pushes the country to breaking point. Matthew Reynolds, the UN Refugee Agency’s regional representative for the United States and the Caribbean, describes it as a crisis ‘on the scale of Syria’.

The situation continues to worsen, with inflation reaching 80,000 per cent in 2018. In early March, a nationwide blackout crippled Venezuela’s power supply, plunging much of the country into darkness for several days. The situation exacerbated already chronic shortages of water, food and medical supplies with difficulties getting international aid into the country meaning many families are surviving on one meal a day.

‘‘People say it’s an economic issue rather than an armed conflict, so it’s not a crisis. When several million people feel they have no choice but to leave, I think you should call it a crisis

Barbara Wegelin

Refugee Officer, IBA Immigration and Nationality Law Committee

Fernando Peláez-Pier, a founding partner of Hoet Peláez Castillo & Duque in Caracas and former IBA President, says the blackout, which is still affecting some areas, has paralysed the country. ‘The situation of hospitals and private clinics has been extremely difficult,’ he says. ‘Public hospitals only had 30 per cent of their electricity supply, while many private hospitals closed their emergency services, weren’t able to receive new patients and some were even forced to evict in-patients.’

More than a million Venezuelans have fled to Colombia, over 500,000 to Peru and 200,000 to Ecuador. A further 300,000 have fled to Argentina, Chile, and Brazil.

Bust of Simon Bolivar, Caracas, Venezuela

Bust of Simon Bolivar, Caracas, Venezuela

Fourteen countries in the region have joined forces to form the Lima Group, which supports democratic transition in Venezuela and has donated considerable humanitarian aid to the country. Peláez-Pier says the support in the region and internationally has been ‘overwhelming’. However, he feels more should be done to help the migrants. ‘The countries that have been most affected in Latin America have been making efforts, but it is definitely a serious social problem,’ he says.

Several Latin American countries tightened their entry requirements in August 2018 after struggling to cope with the influx of migrants. But, in September, when renewing documentation in Venezuela became increasingly costly and time-consuming, 11 Lima Group countries agreed to allow Venezuelans to enter with out-of-date passports. Some Lima Group countries, like Colombia, have only recently honoured their declaration. ‘The decision by Colombia is a good sign and hopefully it leads to other countries taking the same steps,’ says Michael Camilleri, Director of the Rule of Law Program at Inter-American Dialogue, a think tank in Washington, DC.

‘Getting a passport in Venezuela has become just about impossible,’ says Camilleri. ‘I’ve heard that the cost of navigating the system and bribing state employees at different stages of the process to get a new passport is around $5,000,’ he says.

The US, Canada and many European countries have taken the remarkable step of recognising Venezuela’s opposition leader, Juan Guaidó, as President, after allegations that Nicolás Maduro’s re-election was a sham, and attempted to deliver aid to the country. Maduro continues to receive support from a handful of countries in the region – namely Nicaragua and Bolivia – as well as further afield, such as Russia, China, Turkey and Cuba.

Barbara Wegelin is Refugee Officer on the IBA’s Immigration and Nationality Law Committee. ‘The 2015 refugee crisis was synonymous with Syria,’ she says. ‘If you look at Venezuela, people say it’s an economic issue rather than an armed conflict and people are staying in the region and so it’s not a crisis, but I think that’s wrong. When several million people feel that they have no choice but to leave everything behind to find safety elsewhere, I think you should call it a crisis.’

As many as 15,000 Venezuelans, many of them undocumented, have fled to Curaçao (a tiny Dutch-owned island in the Caribbean) swelling the island’s population by 10 per cent.

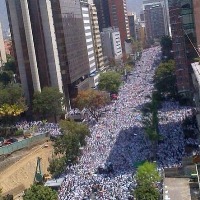

Aerial view of 2014 protests in Caracas

Aerial view of 2014 protests in Caracas

In October, Amnesty International reported immigration raids, indefinite detention and illegal deportation of Venezuelans seeking asylum there and called upon the Netherlands to address these concerns. In February, the Dutch government said it would provide technical assistance with asylum procedures and agreed to make Curaçao into a humanitarian hub for Venezuelan aid.

‘The Netherlands is legally responsible for migration issues in its overseas territories. It needs to step up now and support Curaçao and the other islands, but most of all support the refugees in that region rather than consider this a faraway issue that has nothing to do with Europe,’ says Wegelin. ‘Europe was also ill-equipped in 2015 and most countries are not prepared for massive movements of people who need help.’

Pressure is mounting on international organisations to act. The International Criminal Court has been monitoring events in Venezuela since uprisings in April 2017 and has opened preliminary examinations in the country. The United Nations sent a human rights team to Venezuela in March and it is hoped the UN Human Rights Commissioner, Michelle Bachelet, will visit the country in the coming months.

In 2007, Venezuela severed its ties with the IMF and the World Bank after clearing its debts in happier economic times. Now all the IMF’s 189 member countries must recognise Guaidó’s leadership before it can consider establishing any kind of financing programme for the country. This will be crucial though, as IMF approval could also prompt the World Bank to offer a much-needed financial helping hand.