Could 14th Amendment rule out Trump second term?

William RobertsTuesday 3 October 2023

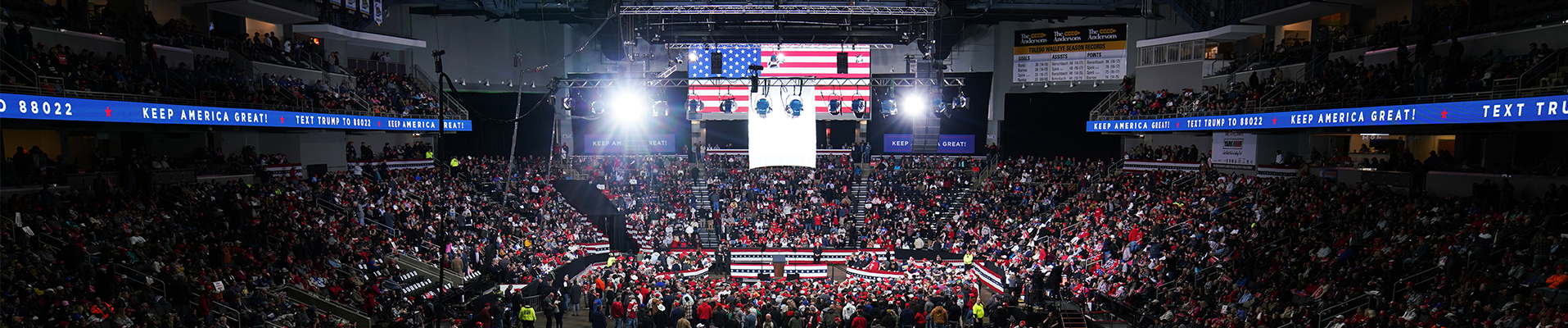

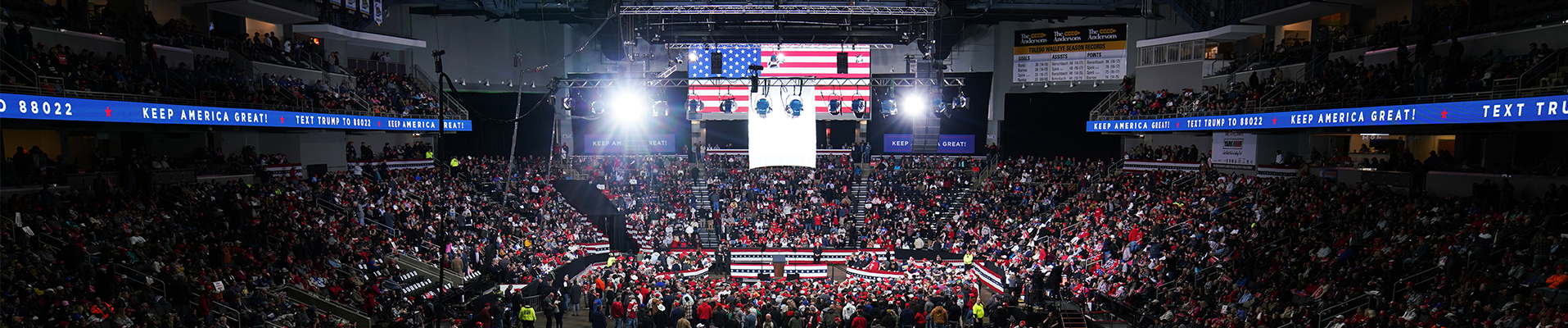

Image caption: Crowd at the Donald Trump MAGA rally in Toledo, OH. tokyo studio/AdobeStock.com

Former US President Donald Trump is leading in public opinion polls for the Republican nomination for president in 2024. Despite his criminal indictments, there’s nothing preventing Trump from running – at least not legally. But a growing number of US constitutional scholars and voter groups are arguing that the 14th Amendment to the US Constitution prohibits Trump from holding US office again.

The 14th Amendment was adopted in 1868 after the US Civil War. Section three of the amendment provides that ‘No person shall […] hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any state, who, having previously taken an oath […] to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same’.

Voters in two states have filed lawsuits to keep Trump off the ballot in 2024. More litigation is expected. The litigation is likely to find its way to the US Supreme Court, which may have to decide whether the Constitution disqualifies Trump. ‘This area of law is a perfect example of the crossroads between law, politics and policy, which makes it a very, very difficult and complicated issue because you have countering theories’, says Mauro M Wolfe, Member of the IBA Criminal Law Committee Advisory Board and a litigator at law firm Duane Morris in New York.

Wolfe explains that one way of looking at the 14th Amendment is that it’s very narrow, being designed for those involved in the insurrection and rebellion at the level of a civil war. ‘There are many problems with it legally, one of which is, does [Trump’s] conduct fall within the four corners of the 14th Amendment, as many argue’, he adds.

This area of law is a perfect example of the crossroads between law, politics and policy, which makes it very, very difficult and complicated

Mauro M Wolfe

Member, IBA Criminal Law Committee Advisory Board

As president, Trump was impeached twice by the US House of Representatives, but never convicted by the Senate. He’s been held responsible for defamation in a case involving a decades-old alleged sexual assault, a decision he intends to appeal, while he faces criminal charges in an alleged hush money scheme involving a former adult film star – a scheme that he denies any knowledge of.

None of this legally prevents Trump from running for president again. In years past, any one of these scandals would have derailed a US politician’s prospects – but Trump’s career has shattered such norms. What has people talking about disqualifying Trump from the 2024 presidential ballot is his conduct around the 6 January 2021 riot by his supporters at the US Capitol.

On 6 January, thousands of Trump supporters attended a rally near the White House where Trump claimed in a fiery speech that the 2020 election had been stolen and urged the crowd to march on the Capitol, where Congress was convening to ratify Joe Biden’s win.

Thousands of Trump’s supporters overwhelmed police barricades and swarmed through the Capitol, forcing elected officials into hiding. Five people died – including one police officer – as a result and dozens of police officers were injured, many seriously.

Trump was subsequently impeached by the House for ‘incitement of insurrection’. Had the Senate convicted Trump on the insurrection charge, it could have also chosen to bar him from holding future office. Senate Republicans refused to go so far against the leader of their party and Trump was acquitted. Meanwhile, Trump has argued that on the day of the Capitol attack, he was urging supporters to behave peacefully.

In 2022, Kim Wehle, a constitutional law scholar at the University of Baltimore, wrote in an opinion piece that Congress has the authority to pass legislation enforcing the 14th Amendment’s ban on insurrectionists. ‘Congress […] enacts rules to keep serious constitutional offenders […] from populating and exercising the privileges of the highest office of the land’, Wehle wrote.

The flaw in Wehle’s theory is that the Republicans presently control the House and nearly half of the Senate, making it highly unlikely Congress would act to block Trump from office.

The 14th Amendment theory gained new credence in August however when legal scholars William Baude of the University of Chicago Law School and Michael Paulsen of the School of Law at the University of St Thomas wrote in an academic paper that the 14th Amendment’s section three is ‘self-executing, operating as an immediate disqualification from office, without the need for additional action by Congress’.

Baude and Paulsen sought to dispel what they viewed as misperceptions and mistaken assumptions about the legal operation of section three. ‘Section Three covers a broad range of conduct against the authority of the constitutional order, including many instances of indirect participation or support as “aid or comfort”. It covers a broad range of former offices, including the Presidency’, Baude and Paulsen wrote. ‘In particular, it disqualifies former President Donald Trump, and potentially many others, because of their participation in the attempted overthrow of the 2020 presidential election.’

Key points of Baude and Paulson’s argument were that section three of the 14th Amendment remains enforceable and was not limited to the Civil War; that it doesn’t require Congress to act; and that it can be enforced by state officials and the courts. And as an amendment to the Constitution, it supersedes other potential legal conflicts, such as ex post facto laws.

Former federal Judge J Michael Luttig and Harvard Law professor Laurence Tribe made a similar case in a joint opinion piece, also published in August. ‘The Fourteenth Amendment […] contains within it a protection against the dissolution of the republic by a treasonous president’, they wrote.

Today, Trump faces a raft of serious federal and state criminal charges stemming from the attack on the US Capitol by his supporters and his alleged attempt to use fake electors to overturn the 2020 presidential election, charges he denies. Luttig and Tribe concluded that whether Trump is convicted in those cases is beside the point. ‘The former president’s efforts to overturn the 2020 presidential election, and the resulting attack on the US Capitol, place him squarely within the ambit of the disqualification clause, and he is therefore ineligible to serve as president ever again’, they wrote.

The most pressing question facing the US, Luttig and Tribe posit, isn’t whether Trump is disqualified but whether the country will ‘abide by this clear command of the Fourteenth Amendment’s disqualification clause’.

Not everyone agrees. Michael B Mukasey, of counsel at law firm Debevoise & Plimpton and a former US Attorney General, argues the president is not an ‘officer’ of the US within the framework of the Constitution. Wolfe tends to agree, for a host of reasons. ‘The idea that the 14th amendment is self-executing and would prohibit the measurement of 40 per cent of the voters in the country is astonishing’, Wolfe says. ‘From a technical, US constitutional, due process standpoint, it doesn’t feel right to me.’

‘It doesn’t make sense, no matter what you think of Trump personally, that a political candidate from any country in the world who has 40 per cent of the popular vote would be unilaterally, without due process prohibited from running because of a hyper technical reading of a 150-year-old document’, he adds.

State officials in key swing states Georgia, Michigan and New Hampshire have already said Trump will be on the ballot in 2024 unless a court orders otherwise. ‘We’re not the eligibility police’, Michigan Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson told a national TV news outlet.

Courts are being asked to weigh the issue. The advocacy group Citizens for Responsibility & Ethics in Washington and a group of six individual voters filed suit in a Colorado state court seeking to prevent Trump from being on the ballot. The Minnesota Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in November on a similar challenge.